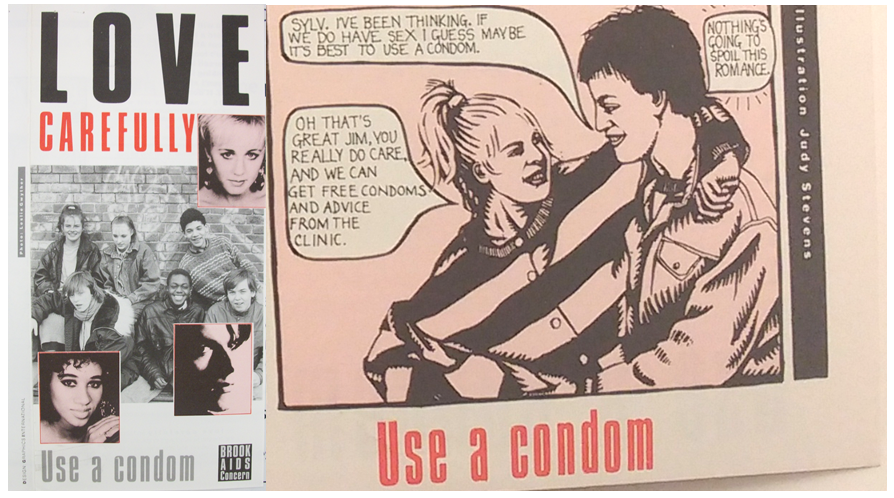

For me, writing history is an emotional process. Last week in the Wellcome Library archive I got the giggles reading an editor’s commentary on a draft of a safer-sex leaflet from 1987. The text was a 1987 Brook pamphlet on condom negotiation and HIV that had a wide print run and several editions. Although innovative, useful and informative, early drafts were a little clunky in places, using a cartoon strip to deliver part of the message on female empowerment and condom use. The cynical editor’s comments on the cartoon were not really that funny; what tickled me was how much they captured my own assessment of the cartoon section as, to quote the editor, a bit too ‘twee’.

‘Nothing’s going to spoil this romance. ‘ Images from the 1987 Brook leaflet Love Carefully , Wellcome Archive, EPH 509 AIDS

The problem with a cartoon intended to promote condom use being twee, or so the editor implied, was that tweeness would make the document less likely to be persuasive to a savvy teenage audience. I’d be inclined to agree, hence my giggling[i], but why? What assumptions was the editor making about the teenage readership and their emotions? What do these assumptions imagine about the effectiveness of deploying particular emotions to persuade adolescents to behave one way or another? What did teenagers really feel when presented with pamphlets that suggested ‘a kiss and a cuddle’ were alternatives to sex?

As a historian, these are the sort of questions I’ve been asking about adult interactions with teenagers for years. I’ve always had trouble with the ‘what kind of historian are you?’ question whenever it comes up. In fact, when asked, I often shrug my shoulders, gesticulate dismissively, and claim not to be a proper historian at all, saying ‘I just like writing about scaring children’. Identity is multifaceted, situational and at least partly performative – or so I’ve argued for the past 5 years – so this is hardly surprising. It’s not an easy question for a historian of identity (which is sometimes what I say I am). My CV will tell you I’ve got an MA in cultural history and a PhD in the history of science, technology and medicine, but really, honestly, I’m here because I do like writing about scaring children. My MA thesis was, at its heart, about adults’ decisions to frighten children so they’d be persuaded to fight for a nuclear free future, and more nebulously, a future free from structural violence, particularly class and gender inequalities. This project, which centred on the two 1980s young adult science fiction novels Brother in the Land and Children of the Dust, convinced me that a more expansive engagement with this textual approach would work to find out how anxious adults attempted to represent HIV positive identities to children and adolescents, interrogating adult motives and asking what behaviours they were hoping to prevent or encourage in their young audience. My PhD, titled ‘[Re]inventing Childhood in the Age of AIDS: The Representation of HIV positive Identities to Children and Adolescents in Britain, 1983-1997’, drew on a large variety of children’s media to interrogate what adults hoped to gain from representing HIV positive identities to children and how they imagined their young audiences.

Perhaps it’s not surprising that I increasingly feel the label ‘historian of emotion’ offers the most helpful clues to exactly what kind of contemporary historian I am: both of these earlier projects were interested in the cultural work done by emotion and the production of deliberately emotive texts. But does this research really make me a historian of emotion? In a narrow sense, probably. However, while I was at pains to emphasise the creation, cause, interaction and context of emotions, I’m not sure I truly located the emotions I studied in a history beyond my narrow Thatcher-era scope. While some historians will fall into the trap of treating emotions as universal elements of the human experience, I fell into the opposite trap, treating emotions as such unique and ephemeral components of experience that they seemed to have no real history, only specificity, existing in a mere moment, the circumstances of which could be described, but only to create a silhouette of what my actors had personally been made to feel. But those feelings have a history, something which falls between the specific interactional moment of a single actor’s experience and the long duree.

In rewriting my PhD for publication as a monograph I’ll be revisiting ideas around adult anxiety and parental love, questioning the specificity of these emotions and looking for areas of continuity outside my time period through a more conscious emphasis on emotion. In paying more attention to the history of these emotions I hope to get more from the material by finding new questions to ask of it, adding some of the long duree to the emotional history I’ve already written.

And what else will I be doing for the next 15 months? As I’ve explained elsewhere, I’ll be working with each member of the Placing the Public in Public Health team to unpick the place of emotion in some specific areas of British post-war public health. I’ll join Gareth Millward’s project to look at vaccination and the public, Peder Clark’s to investigate the convergent history of heart disease and stress, Daisy Payling’s to investigate the emotional labour involved in health survey participation and Alex Mold’s to assess the use of emotion in public health posters. These collaborations completed, my time on Placing the Public in Public Health project will be rounded off with a conference themed around public health and emotion, past and present in July 2018. This will allow us to consolidate our work on public health and emotion as a group, but also to think about what other new opportunities an enagement with emotion can create.

Personally, I hope the next 15 months will allow me to think more deeply about the intimate connection between the history of emotion and public health and to question what it has to offer to the challenges specific to writing contemporary histories of sexual health and childhood. In doing so, I’m hoping to find ways to write about scaring, comforting and empowering children which interrogate and historicise the emotions of the past while ensuring those who felt them have a voice in the history I write. Ambitious maybe, but I’ve got a good feeling about it all.

Hannah is always happy to discuss their research and can be contacted via Hannah.kershaw@lshtm.ac.uk or twitter @sexhistorian

Hannah Elizabeth, 16 May 2017

[i] I’m far from the only historian to get the giggles in the archive, or indeed in reaction to other methods of primary research. The Wellcome Witness Seminar conducted to mark Brook’s 50th anniversary is a fascinating listen interspersed with laughter, providing both an informative couple of hours of history and also a lovely example of oral history as an innately emotional methodology. For those interested, the Southern Oral History Programme’s Press Record podcast on emotion and oral history provides a moving discussion on the challenges the emotional nature of this methodology presents.