In 1944, the Daily Express columnist Beachcomber mocked social surveys by imagining a study on the accuracy of the measurement ‘a hairsbreadth.’

He wrote; ‘let [researchers from Gallup and Mass Observation] tear people’s hair out in handfuls in the cause of accuracy. Ninety-three per cent wouldn’t know or care.’[1]

The comedic value lay in the juxtaposition of the extreme and absurd, but Beachcomber’s joke served a dual purpose. It framed the survey as a violation and also suggested high rates of ignorance or apathy among the public.

‘Don’t Knows’ – people who could not or would not answer survey questions when asked – frustrated social surveyors. In 1947, Mass Observation wrote that ‘everyone seriously engaged in opinion research is only too painfully conscious’ of the problem.[2]

Mass Observation tried to explain the ‘Don’t Knows,’ writing that they had to be more than ‘dumb, uninterested or of no consequence.’ The alternative was to suggest that the British were ‘rapidly becoming a nation of morons.’[3] As unthinkable as this was, more worrying was the suggestion that the ‘Don’t Knows’ included ‘tomorrow’s fascists alongside the perpetually dumb.’

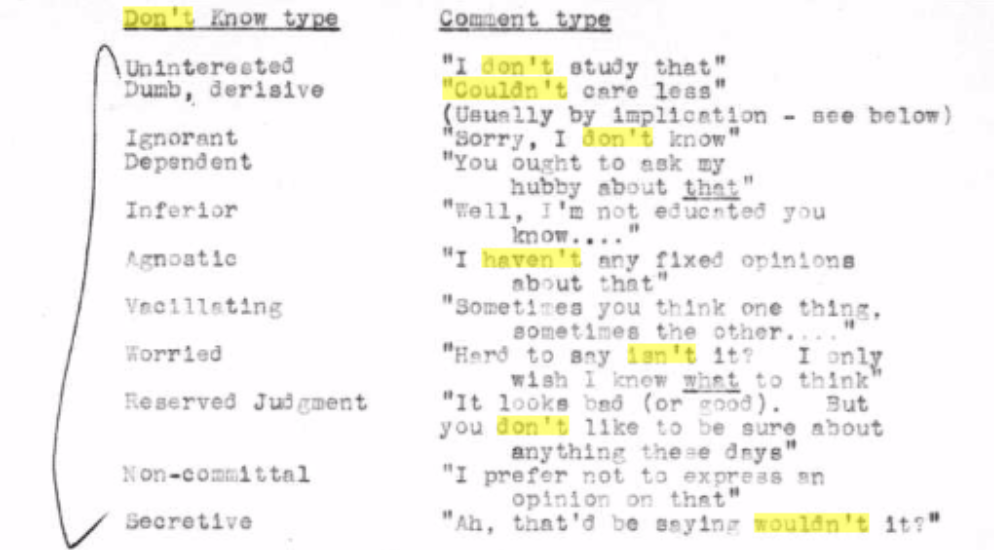

Deciding that the phenomenon needed investigation, Mass Observation formulated eleven types of ‘Don’t Know’: including categories such as ‘Dumb, derisive’, ‘Reserved Judgment’, and ‘Secretive.’[4]

Mass Observation’s nine ‘Don’t Know’ types (SxMOA1/12/12/6: Anatomy of the ‘Don’t Knows’, 1947)

Mass Observation gave voices to the ‘Don’t Knows’ – assigning the categories to members of the public based on the ‘type of verbal comment’ they made to interviewers.

Researchers tried to identify the ‘Don’t Knows’ and discern their motivations. Their speculations about the reasons behind respondents’ refusal to offer opinions were influenced by contemporary understandings of class and gender. Women and the ‘undereducated’ were the acknowledged ‘villains in the piece,’ and researchers imagined other broad types, including; ‘the man who can’t make up his mind; the woman who can’t be bothered; the middle class person who can’t decide which side of the fence to jump; and the working class person who isn’t interested in fences.’[5]

Ultimately, Mass Observation found that ‘who doesn’t know depends on the question being asked,’ but concluded that questions on topics ‘nearer the home and nearer the heart’ produced fewer ‘Don’t Knows’, while embarrassment swelled the ranks.

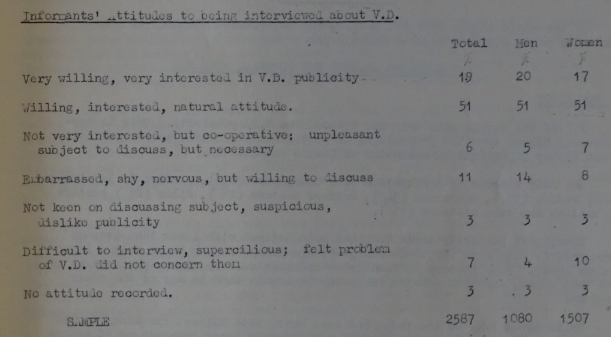

The embarrassment factor had been acknowledged a few years earlier by the Government Social Survey department. In their 1943 survey into health education campaigns on venereal disease, eight percent of those surveyed claimed no knowledge of how venereal diseases were spread. Discussing this result, the GSS pondered whether the question was a ‘difficult one for reticent people to answer’ and suggested that ‘“don’t know” may in some cases conceal shyness.’[6] When conducting a follow-up inquiry in 1944, the GSS provided space on the recording schedule for the investigators to comment on each ‘informant’s attitude to [the] subject of VD’ and record their own ‘interpretation’ of said attitude.[7] These comments were collated and the higher proportion of men expressing embarrassment was attributed to the fact that investigators were usually women.

Informants’ attitudes to being interviewed about V.D. (TNA: RG23/56, P.J. Wilson and V. Barker, ‘The Campaign Against Venereal Diseases’, January 1944, p.3.)

Public health researchers today still find themselves dealing with embarrassment. One interviewer working on the National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles, talking about participant use of computers to input responses, joked that ‘it’s probably just as well that you don’t have the eye contact’ (p.57). But as this Natsal-3 report shows, analyses of participants’ responses to ‘difficult’ questions has developed since the 1940s.

Outside of public health, polling companies still struggle with the phenomenon of the ‘Don’t Know.’ And with discussions of ‘shy Tories’ and the ‘stigma’ of voting UKIP dominating analysis of polling failures after the 2015 General Election, it could be argued that Mass Observation’s ‘Don’t Know who daren’t say’ is still instantly recognisable to opinion researchers today.

Daisy Payling, 19 January 2017.

[1] Daily Express, Friday January 7th 1944, 3.

[2] Mass Observation Online, SxMOA1/12/12/6: Anatomy of the ‘Don’t Knows’, 1947.

[3] ibid.

[4] ibid.

[5] ibid.

[6] The National Archives: RG23/38, Wartime Social Survey, ‘The Campaign Against Venereal Diseases’, April 1943.

[7] TNA: RG23/56, P.J. Wilson and V. Barker, ‘The Campaign Against Venereal Diseases’, January 1944, 2.