The belief that ’10,000’ steps is good for you is relatively ingrained fitness lore worldwide. The belief has spread through high profile global step fitness challenges and the prevalence of relatively cheap, accurate digital step counters. However, before we all became fixated with collecting our own personal health stats and viewing everything as units of ‘steps’, there was a time when such a practice was peculiar: namely the 1970s* [* or, any other time but for narrative purposes let’s say the 1970s].

Pedometer from the 1970s

Back then, pedometers were hardly known and were mainly used as a medical instrument. It was for this purpose they were used by groups of randomly chosen male middle-aged civil servants measure rates of exercise in 1970, as part of Whitehall Study. The study aim was to measure exercise in a typical week that would account for walking at work and during leisure time. The potential effect of the level of physical exertion and rates of coronary heart disease [CHD] had then only recently been indicated, with the MRC trial of anticoagulant therapy on myocardial infarction (1969) noticing that rates of CHD were more frequent and fatal within inactive workers.

The follow-up study involved randomly selected Whitehall Study volunteers receiving an invitation from Dr Geoffrey Rose, the study’s lead investigator, whether they would be willing to participate in the study. Volunteers who agreed to participate in the study would then receive a mileage record sheet, pedometer and a pedometer instruction sheet.

The alien nature of the pedometer was encapsulated by Dr Rose’s description of a pedometer as a little instrument looking like a pocket watch, which clips onto your trousers, or goes in a pocket, and the dial records the distance that the wearer walks. The instructions sheet sent to those volunteers emphasized the care needed to prevent false readings through any other transport other than by foot, as it was reliable to record mileage by bus, train, car or bicycle.

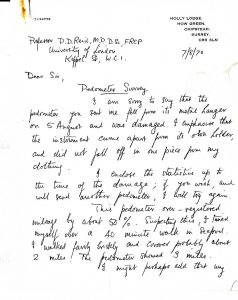

Extract from a letter from a volunteer expressing his difficulty in performing test due to unusual work circumstances and a German exchange student.

The correspondence within the archives leave a record of the difficulty associated in getting volunteers to ‘volunteer’, with several letters back to Geoffrey Rose explaining their difficulties in participating. Letters received back were often apologetic citing holidays, overseas placements or change in work environment. Others raised the difficulty of finding a typical working week to undergo the test, as the letter expresses below (though doesn’t fully make clear how hosting a German exchange student was going to effect the test).

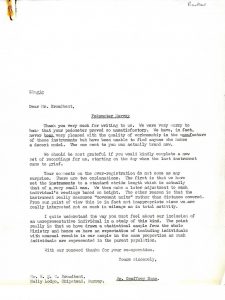

The researchers also had to factor in the unreliability of the post office in delivering the pedometers and the failure of the instrument itself. Mr Broadbent noted that ‘this pedometer over-registered mileage by about 50%. Suspecting this, I timed myself over a 40-minute walk in Seaford. I walked fairly briskly and covered probably about 2 miles. The pedometer showed 3 miles”. Dr Rose wrote back a very candid response noting first that pedometer performance had never been satisfactory, and that the over-representation was possibly down to the average stride with some individuals having a much larger stride than the average.

It does not seem that the results of the pedometer trial were the basis of any major changes within the direction of the Whitehall Study but displayed how the study had expanded from its original remit on surveying cardiorespiratory risk to include physical exercise and social factors. The longitudinal data from the study confirmed that high physical exercise rates gave protection from a range of mortality outcomes and not just CHD [G. David Batty et al. 2010].

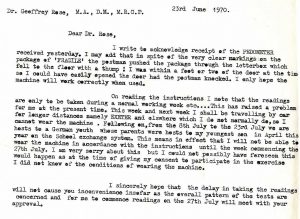

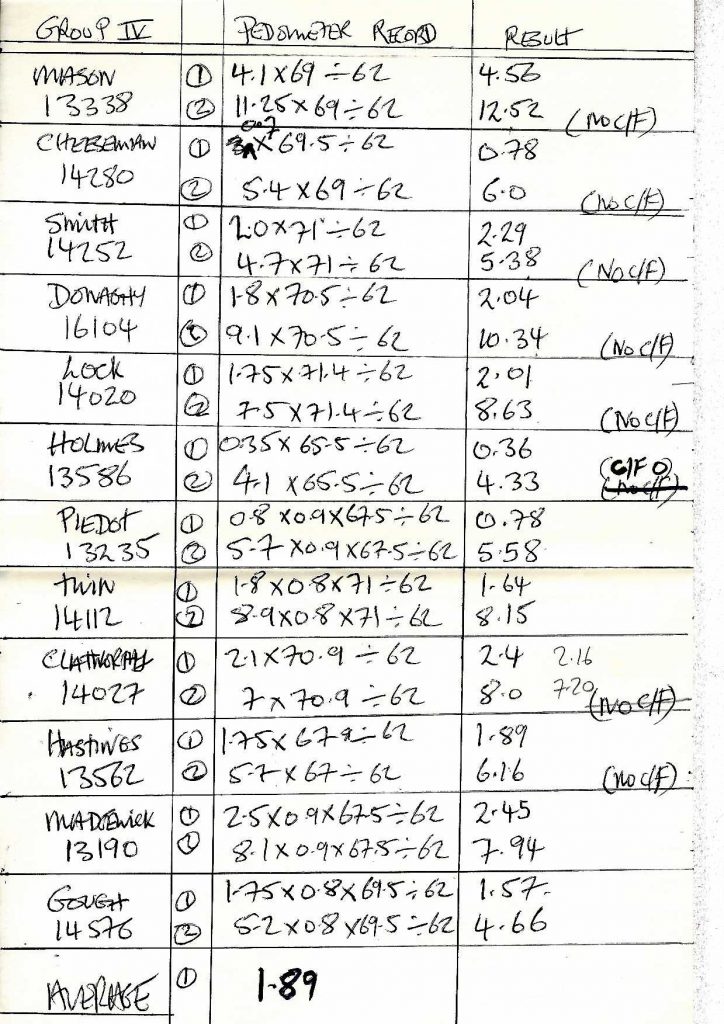

Table showing some of the results from pedometer trial group. Average miles walked for the group was 1.89 miles or 3992 steps if you prefer

References:

Forget walking 10,000 steps a day – I have another solution, Stuart Heritage, The Guardian, Tuesday 21 February 2017 13.32 GMT, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2017/feb/21/forget-walking-10000-steps-a-day-i-have-another-solution-fitness-trackers

Physical Activity and Coronary Heart Disease, Geoffrey Rose, Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine, Volume 62, November 1969, pp 1183-1188

Walking Pace, Leisure Time Physical Activity, and Resting Heart Rate in Relation to Disease-Specific Mortality in London: 40 Years Follow-Up of the Original Whitehall Study. An Update of Our Work with Professor Jerry N. Morris (1910–2009), G. David Batty, Martin J Shipley, Mika Kivimaki, Michael Marmot & George Davey Smith, Annals of Epidemiology, 2010