As we’ve already seen in this blog series, the Historical Collection furnishes a huge variety of pre-twentieth-century material that is of value to anyone interested in the history of science or social studies or LSHTM as an institution. The work done to improve catalogue records for this Collection added valuable information on the book’s binding and material condition, as well as information on past ownership, provenance, and if it contains culturally sensitive material.

Volumes on India appear frequently in the Collection, something likely unsurprising given the way LSHTM was founded in response to the health research demands of the British Empire. This post will investigate what just a few of the books’ own provenances and history might tell us in conjunction with their contents. It will focus especially on the material we have that looks both at India and at food and foodstuffs. It’ll suggest that writers at the time saw food as an important resource for furthering and maintaining the power of the British Empire, in both a logistical and cultural sense.

Banting in India

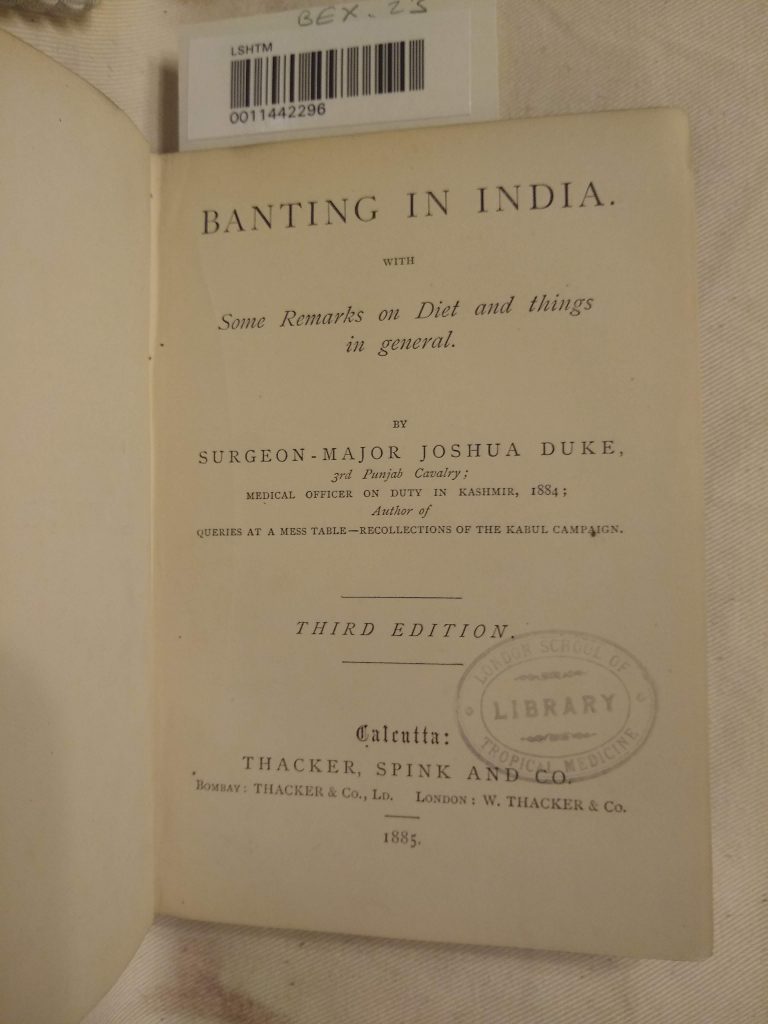

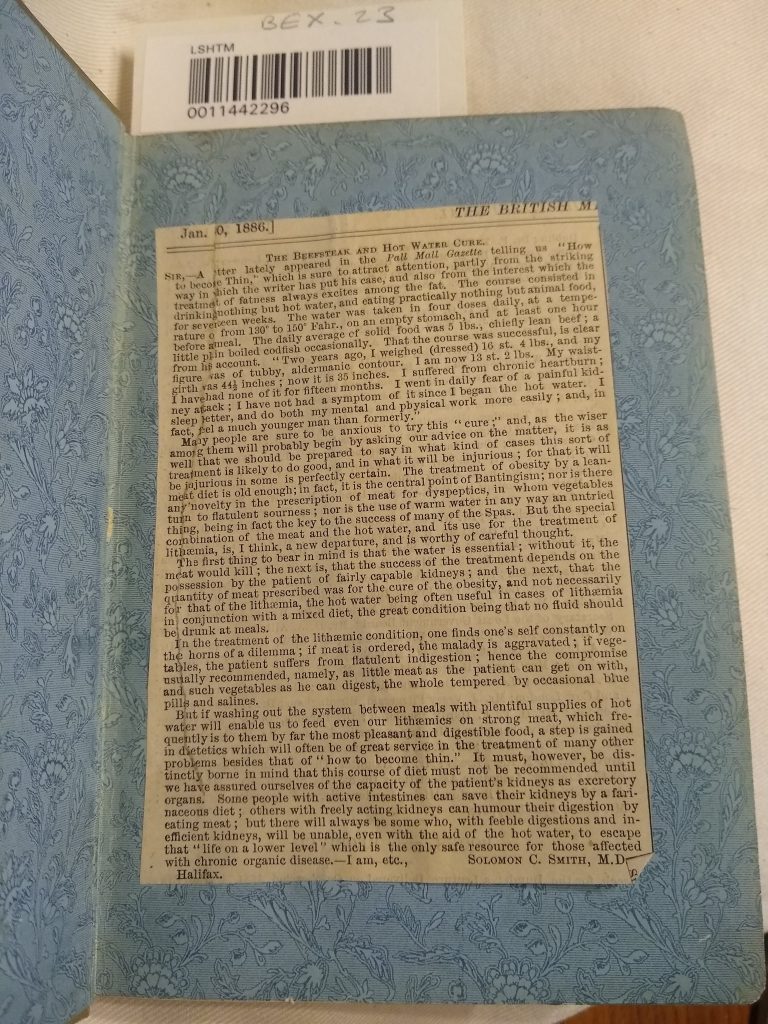

This volume, also available as a digitised copy on the Internet Archive, requires some explanation, as the title is rather enigmatic for anyone not au fait with dieting trends of the mid-1800s. “Banting” was a diet popularised in England by William Banting, an undertaker, in the 1860s. Its key feature was restricted carbohydrate consumption for the purpose of weight loss. Indeed, the short letter to the Pall Mall Gazette pasted into the front endpapers of our copy is also diet-related. It discusses an extreme meat-and-water diet (sorry: “beefsteak and hot water cure”) and offers advice on how to follow it “safely.”

In this volume, Joshua Duke attempted to make recommendations about how the diet could be followed in India. There is some ambiguity in the text itself about exactly who in India was meant to be following this diet. For instance, the appeals in the opening chapter of the third edition (the one in our collection) to the so-called traditional diet and lifestyle of the English and the iniquities of modern “estheticism,” or the occasional implications that its imagined audience was a British soldier, might suggest its main audience was those who had travelled from Britain to India as part of the colonial administration. Yet the final chapter, explaining how his modified diet might be applied to a Hindu or Muslim diet, implies that it was meant to have wider appeal. Jaime Michelle Miller explored how Duke’s book fitted into the adoption of an English-styled asceticism in India and the ways British and Indian people in India imagined themselves and their diets in a PhD thesis on Banting.

Various other passages also stand out. Duke’s recommendation to consume extracts from the coca plant to alleviate the difficulties of dieting rings differently nowadays, given that that coca’s best-known product is cocaine. The association of diet and health was not entirely unique in the context of post-1850s India, either. Sam Goodman has analysed how writers of this time dealt with food and drink as medicine.

“In the latter half of the present century, the rapid strides of civilization and forced education have altered a great deal of the former simplicity of English men and women. The school-master is abroad in every corner of the land, and the beautiful rusticity of country-life is being materially altered. Books of every kind and description, whether good or bad, can be purchased for a small sum. New religious sects are springing up every day, while atheism, and as a necessary result, immorality, have, hand in hand, made rapid strides … Effeminacy, unmanliness, and perhaps unwomanliness are represented by the Esthete and Estheticism.”

Joshua Duke, Banting in India, 3rd ed., pp. 9-10.

Joshua Duke was, according to his 1920 obituary in the BMJ, a lifelong medic in the British Army. The third of a Clapham doctor’s eight sons, he was a surgeon in Australia and Kashmir, also fighting in the Second Anglo-Afghan War. He eventually retired in 1902 but rejoined the army in 1914 for the First World War, working at the “York Place Indian Hospital” in Brighton and subsequently in Bermondsey. His publishing record reflects his career and the places in which he was active. Aside from Banting in India, he also produced works entitled Queries at a mess table: what shall I eat? what shall I drink?; Recollections of the Kabul Campaign, Kashmir and Jammu: A guide for visitors; and The Prevention of Cholera.

The BMJ obituary also notes that his son, Dr H. Lyndhurst Duke, was also “of the Colonial Service (Uganda)”. This younger Duke appears in the Imperial War Museum’s Lives of the First World War project as a captain in the Uganda Medical Services and later as deputy director and then director of the Human Trypanosomiasis Research Institute in Entebbe, where he published extensively on his experiments with and on trypanosomiasis, including on local volunteers. The Duke family therefore contributed two figures to colonial medicine in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Each of them sought to further contribute to the British Empire’s colonialist endeavours by disseminating knowledge gained from their military and medical work. The profit made by the Empire from either “improving” the diets and lifestyles of local Indian elites and soldiers stationed there, or from improving treatments for trypanosomiasis, was always paramount.

Our copy of Banting in India has little information on when precisely it entered the Library, though it does have a tantalisingly vague handwritten inscription on the title page that says, “Presented by Dr Duncan.” This might have been Dr James T. Duncan, who worked at the School in the early and mid-twentieth century. If that is the case, then the book entered the library already as something of a historical artefact. But while the society Joshua Duke described and engaged with had changed, the machinery of empire continued to rumble on: for instance, the Indian Independence Act of 1947 was likely not yet passed by the time the library received the book.

Food-Grains of India

Other aspects of food in India also preoccupied writers. This volume, written by Arthur Herbert Church and published in 1886, is an excellent example and is also available online at the Internet Archive. In terms of subject matter and aims, Herbert is explicit about his concerns in the Preface:

“The present Handbook has been prepared mainly with the object of furnishing to Indian officials and to students of Indian agriculture a compact account of the alimentary value of the chief Food-Grains of our Eastern Empire.”

A. H. Church, Food-Grains of India, p. vii.

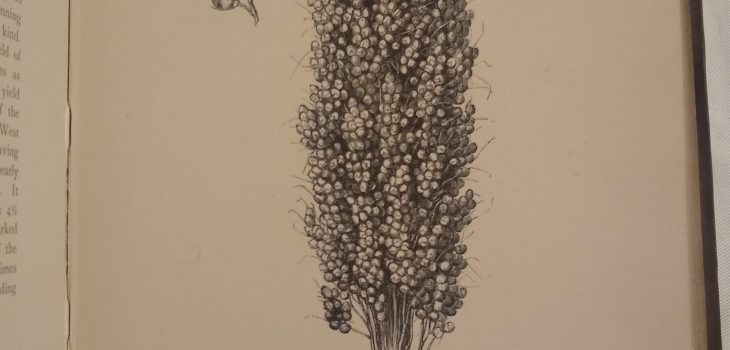

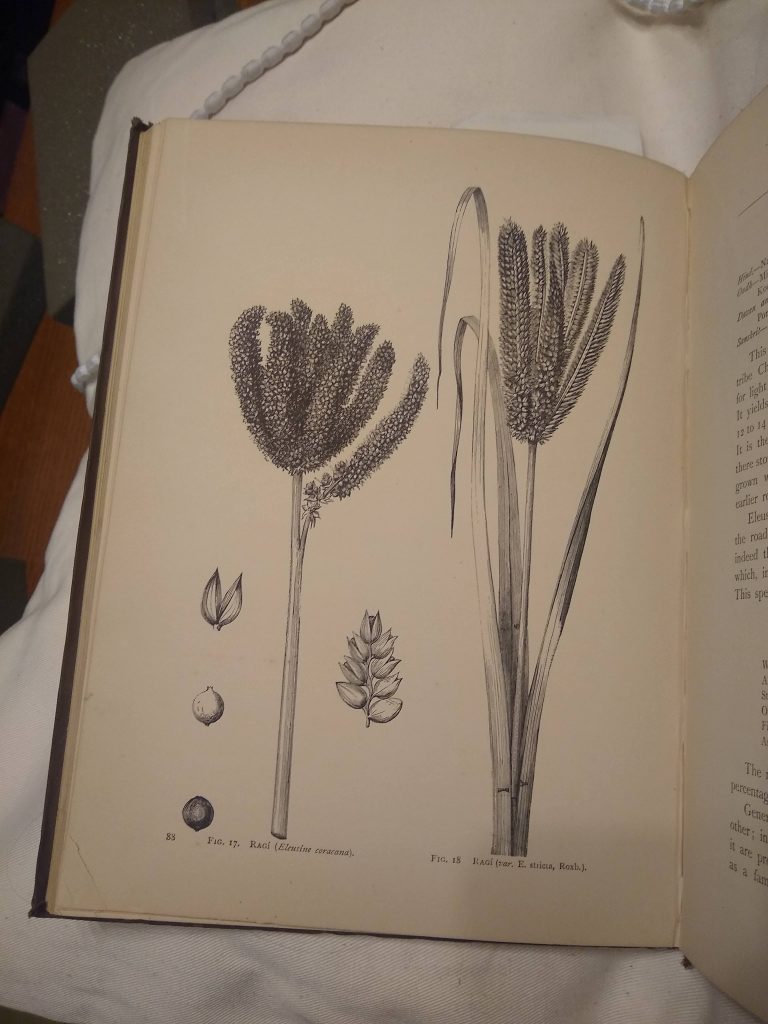

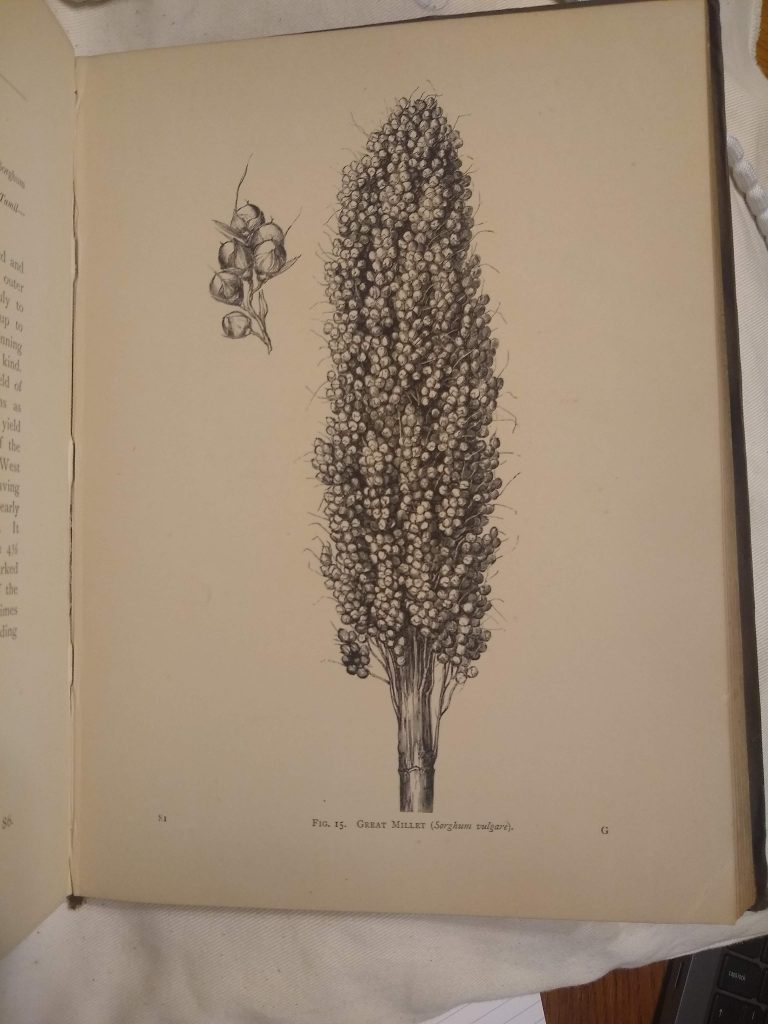

The volume’s textual material covers, firstly, what was then known about the chemical composition of foodstuffs (i.e., water, fibre, starch, etc.), the then discusses ideal diets, and finally offers a summary of different crops grown in India, from cereals to buckwheats and pulses. It is also illustrated throughout with black-and-white woodcut illustrations of the plants in question.

Church was known as both an artist and a chemist; indeed, he held the post of professor of chemistry at the Royal Academy of Art. Two of his paintings seem to be held at the Victoria and Albert Museum where they were donated after his death, apparently according to his wishes. Aside from this volume, he published one other handbook on food and otherwise many books on on pottery, dyes, and mineralogy – his Wikipedia article gives an extensive list of these publications. He was also previously associated with the Royal Agricultural College in Cirencester, which goes some way to explaining his dual interests.

There is little biographical evidence, however, that links Church to India. Indeed, his Preface to this volume implies that he might never have been to India and instead relied on secondary sources and analyses performed in Britain on samples. He says, regarding “Indian” names for plants, that “I have no first-hand knowledge of the subject, and, having been obliged to gather the names of places and products from a great variety of sources, neither accuracy nor uniformity of transliteration has been secured.” That he was able to compile a book on this subject is testament to the extent of the circulation of information in Britain about India. But it also demonstrates the subordination of Indian agriculture to analysts thousands of miles away: data and samples from India were transported to Britain, analysed and compiled by an English writer, then shipped back to officials to inform their decision making.

Much like Banting in India, this volume cannot be said to have been at LSHTM during the period immediately after it was published. A bookplate in it states that it was accessioned on 15th January 1959. That means that it was likely to have been a historical curiosity rather than an actively referenced contemporary work.

How to get these books

Library users are welcome to consult any of the physical copies of books on Library premises. Each of the books discussed above has their catalogue entry linked in the section title. To reserve a book for consultation, just go to their catalogue entry on Discover while logged into your LSHTM account and follow the instructions underneath the heading “Get It.” You’ll receive an email when it’s available. However, please note that you will need to read these books within the Library and cannot borrow them like most other resources.