Sir Shirley Foster Murphy was born in 1848 and educated University College School and Guy’s Hospital. His work included being the Vice President of Royal Sanitary Institute, and was involved in a range of societies and organisations including; Society of Medical Officers of Health, Epidemiological Section Royal Society of Medicine and Royal Statistical Society and examiner in Public Health, Royal Colleges of Physicians and Surgeons.

He was a Bissett Hawkins Medallist, Royal College of Physicians; Jenner Medallist, Royal Society of Medicine; Medical Officer of Health, Administrative County of London and a member of Royal Commission on Tuberculosis. Murphy was knighted in 1904; awarded Knight Commander Order of the British Empire, 1919, and became a fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons. He died in 1923.

His collection is fascinating and nearly unique within the LSHTM collections, with a large focus on the history of the slaughter of meat for food, and later the slaughterhouses in Europe in the late 1800s – early 1900s; including the efforts taken to better sanitise them.

Slaughterhouses as a form have been around for centuries. What is later referred to as a ‘public slaughterhouse’ has origins at a minimum in ancient Rome, where before 300BC, animals were slaughtered in the Forum in the open air, and as time went on (to meet the convenience of butchers) animals were slaughtered near the River Tiber. These forms of slaughterhouses existed in the UK as well, at least until the Public Health Act of 1875.

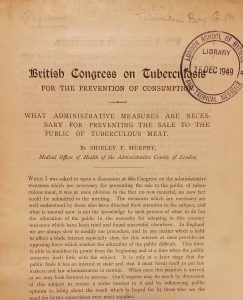

”What adminstrative measures are necessary for preventing the sale to the public of tuberculous meat” GB 0809 Murphy/05

The Public Health Act of 1875 changed the development of slaughterhouses, which until then had been very loosely regulated. The concern about better regulation within slaughterhouses became a matter for public health, as there was evidence of disease (most concerning was Tuberculosis) within the meat that killed for the purpose of human consumption. Private slaughterhouses become more common in England after the passing of the Public Health Act in 1875, and these slaughterhouses were licensed annually by a local authority. Private slaughterhouses that existed prior to this act are registered but did not have to be subject to the annual licensing. While some sanitary authorities enforced bylaws and regulations regarding sanitation of slaughterhouses, this was not widespread.

Slaughterhouses were of two types; private (belonging to individual butchers) and public which are for communities (for example, in large towns). In the early 1800s in England, the power to provide public slaughterhouses had been given to municipal corporations, but was sparingly used. In the 1875 Public Health Act this power was extended to include all urban authorities as well.

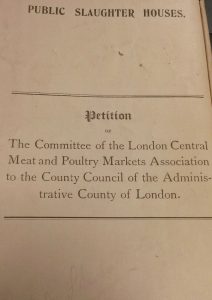

A petition of the Committee of the London Central Meat and Poultry Markets Association to the County Council of the Administrative County of London GB 0809 Murphy/02

In England, often public slaughterhouses were called abattoirs, to differentiate them from the butcher’s associated slaughterhouse. This association created tension during proposals to only allow the slaughter of animals in such public slaughterhouses as opposed to those run by the butchers.

In London, there were disagreements between the County Council and The Committee of the London Central Meat and Poultry Markets Association, of which the latter wrote to the Council outlining some key points as to why the proposal to close down private slaughterhouses out of concern of a lack of meat inspection was a bad idea. They propose that they are not at all adverse to proper meat inspection and that the private slaughterhouses serve a purpose within their community, through supplying meat for food.

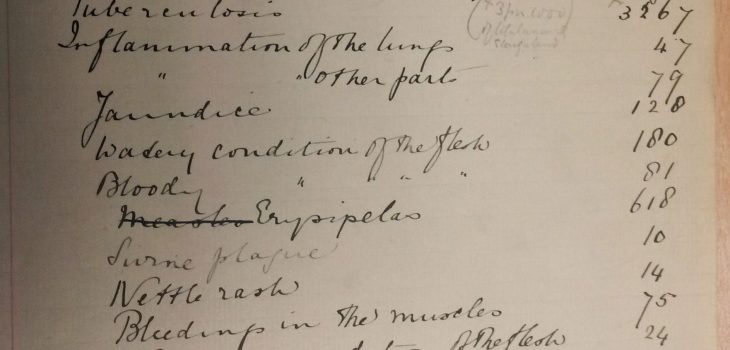

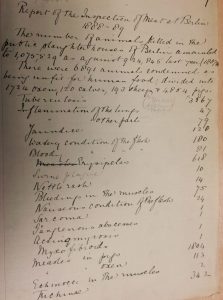

An example of the responses of the Committee of the London Central Meat and Poultry Markets Association within the petition. GB 0809 Murphy/02

Murphy challenged many of their points, maintaining that in order to prevent the sale of tuberculous meat, the slaughter of all animals intended for consumption should be in public slaughterhouses and that competent meat inspections are employed.

In England the meat inspection differed from the rest of Europe, as the butcher was the one to inspect the meat to determine whether it was fit for human consumption, as he was presumed to have sufficient knowledge for that purpose. While other counties employed a systematic meat inspection by the local authority. This was seen by Murphy as being the preferred method, referring to Copenhagen for example, who used a stamping system for meat butchered of first class which was ‘quite sound’ and second class which would be fit for consumption after cooking.

All other meat that did not make the 1st or 2nd class stamp would be destroyed through burning. Murphy hoped to bring the practices of continental Europe to England to allow for safer meat.

To access this unusual collection, contact us at archives@lshtm.ac.uk to book an appointment.