Today, we will take a quick look at Henry C. Burdett’s book Cottage Hospitals General, Fever, and Convalescent. This book is part of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine Library’s historical collection and can be found under the Barnard Classification Scheme classmark of SYBH (Cottage Hospitals).

Cottage hospitals played an important part in the evolution of healthcare from the mid-19th century to the present day. These small, community-based hospitals provided accessible medical care to rural (and semi-rural) populations, and provided access to healthcare for those who did not have the money to access treatments.

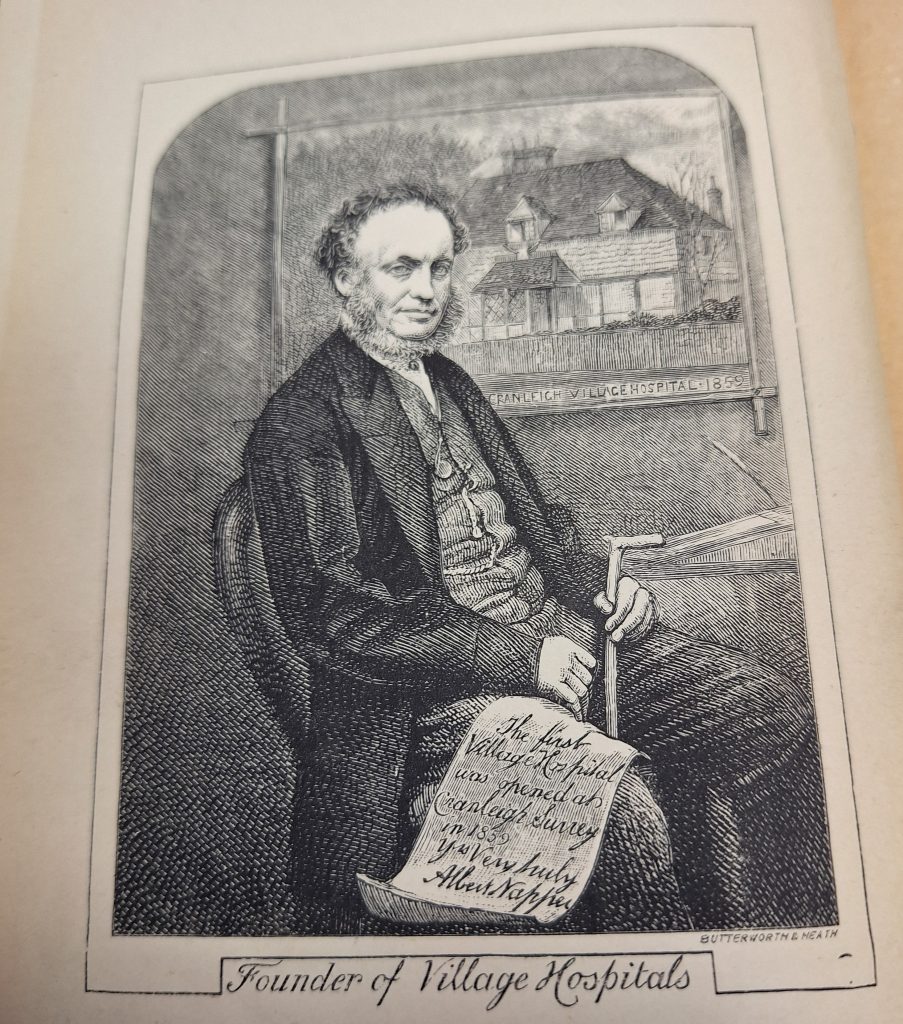

The concept of cottage hospitals was largely introduced by Albert Napper, a surgeon, who founded the first cottage hospital in Cranleigh, Surrey, in 1859. His aim was to provide medical care to rural communities who were too far from larger urban hospitals. The book Cottage Hospitals pays tribute to Napper by using his portrait as a book plate right before the title page, a real honour of the man’s importance.

Local communities often funded and maintained cottage hospitals, including donations from wealthy patrons and fundraising activities. By the mid-late 1800s, the failures of laissez-faire economics in Victorian Britain were becoming glaringly obvious. Poverty was rife, and many people were unable to access healthcare. Most community hospitals were started up by doctors who wanted to help and funded by local wealthy people to ensure the poor had access to cheap local-based healthcare.

Following the success of the Cranleigh Hospital, the model quickly spread across the UK. By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, hundreds of cottage hospitals existed throughout England. The Cottage Hospitals book provides lists of cottage hospitals, the costs to patients and whether they would provide care to ‘paupers’ (yes, some of these hospitals designed to provide the poor with healthcare would still refuse treatment to those who had no means to afford it). I am amused by some of the names of towns listed… Croydon, Harrow, Hillingdon… today, these towns are bustling parts of the London sprawl.

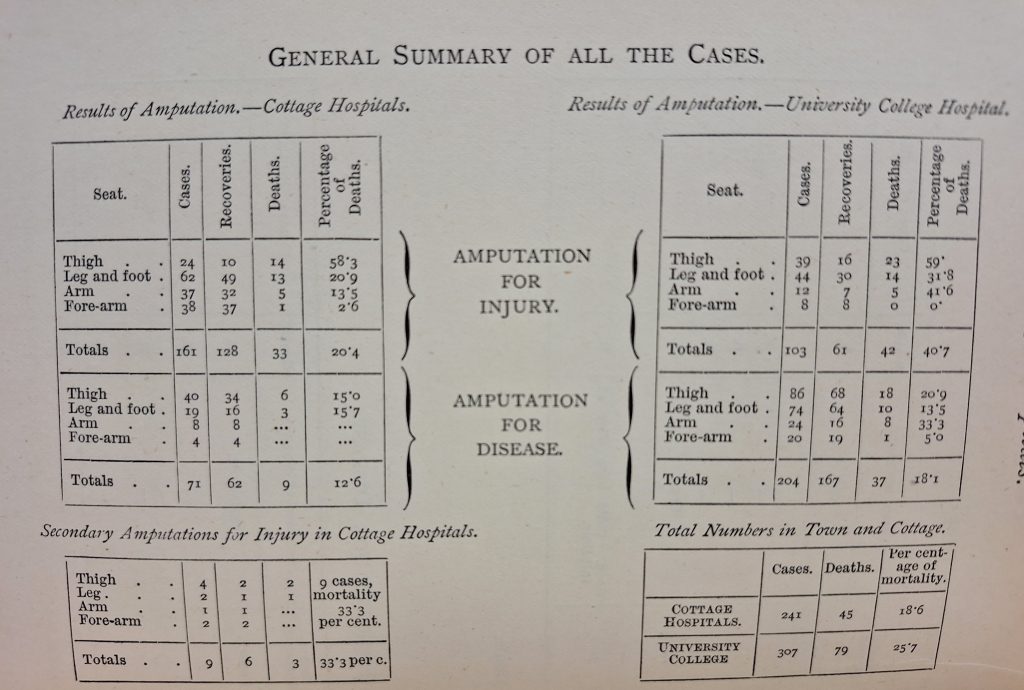

These hospitals typically offered general medical and surgical care, maternity services, and treatment for minor injuries and illnesses. Some also specialised in recovery and treating infectious diseases (the ‘fever hospitals’). As the image shows below, local-based treatments, rather than journeys to larger centralised hospitals, provided higher survival rates from dangerous procedures, such as amputations. The book Cottage Hospitals explains that the smaller size of these hospitals allowed for more personalised care and closer relationships between patients and healthcare providers.

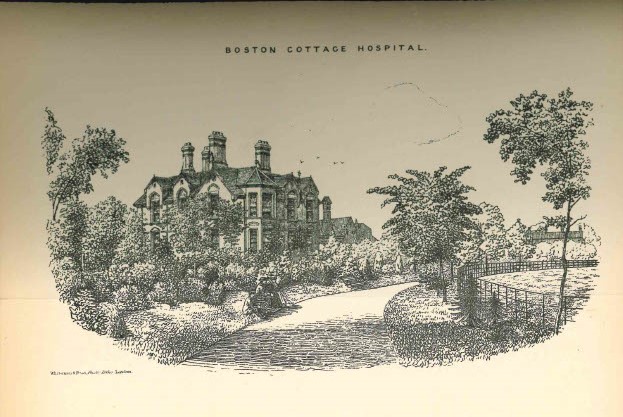

The book provides examples of many floor plans from cottage hospitals around then; they were often modest, with a few beds, an operating room, and basic medical equipment. The emphasis was on practicality and community needs. Some would have separate fever wards or convalescent wards.

The creation of the National Health Service in 1948 brought significant changes. Cottage hospitals were assimilated into the NHS; the focus shifted towards larger, more centralised hospitals. My former local cottage hospital, based in Upper Norwood, was incorporated into the NHS but was inevitably closed down by the mid-1980s, as it could not offer specialised services the larger centralised hospitals in South London could. These things tend to go in cycles, and today, the NHS is looking to take pressure off larger hospitals. The role of smaller facilities specialising in things like outpatient care and rehabilitation are playing a more significant role in healthcare again.

Cottage hospitals played an important role in the development of healthcare in the UK in the mid- to late 1800s, providing accessible and personalised medical care to communities that needed it. This book provides us with a lot of useful information related to the structures of the cottage hospitals, how they were funded, the treatments they provided, and the successes and failures of these largely philanthropic endeavours. It’s an important text for anyone interested in healthcare in Britain pre-National Health Service or the history of public health during the Victorian period.