The London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine in Keppel Street, Bloomsbury was opened in 1929. The balconies on the first floor of the building, outside the Library, are decorated with a frieze of sculptures of ten animals – seven insects, a tick, a snake and a rat – responsible for the transmission of diseases (vectors) or as a symbol of protection (the snake) and adopted by the medical and pharmacological professions. This blog suggests that the addition of a sculpture of the smooth whorls of the shell of the snail Bulinus, a vector of Schistosoma sp., the parasitic worm causing schistosomiasis in Africa and the Middle East, would have been a very suitable model for inclusion in the frieze.

The sculptures outside the LSHTM building

During World War I British troops stationed in Egypt were severely affected by a parasitic infection caused by the flatworm, Schistosoma, in their blood vessels, damaging internal organs and causing cramps, anaemia, lethargy and severe pain. The parasitic nature of the disease, schistosomiasis (or Bilharzia), was known since 1851 but not its method of infection. The School’s helminthologist Robert Thomson Leiper (1881-1969) went out to Africa to investigate in 1915. In a very short time Leiper and his team discovered that stages of the schistosome life cycle had to pass through the bodies of aquatic snail intermediate hosts before they could infect humans.

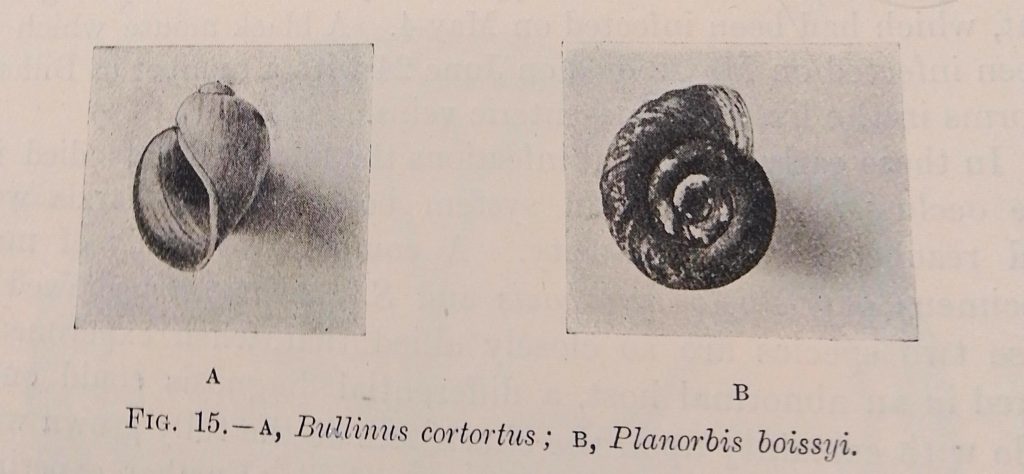

Snails Bulinus and Planorbis – vectors of Schistosoma (Leiper 1918 : 41)

Bulinus sp. shells range from between 4-22 mm in height; Planorbis sp. shells are of variable height, and have a diameter of 7-22 mm and 3-7 whorls.

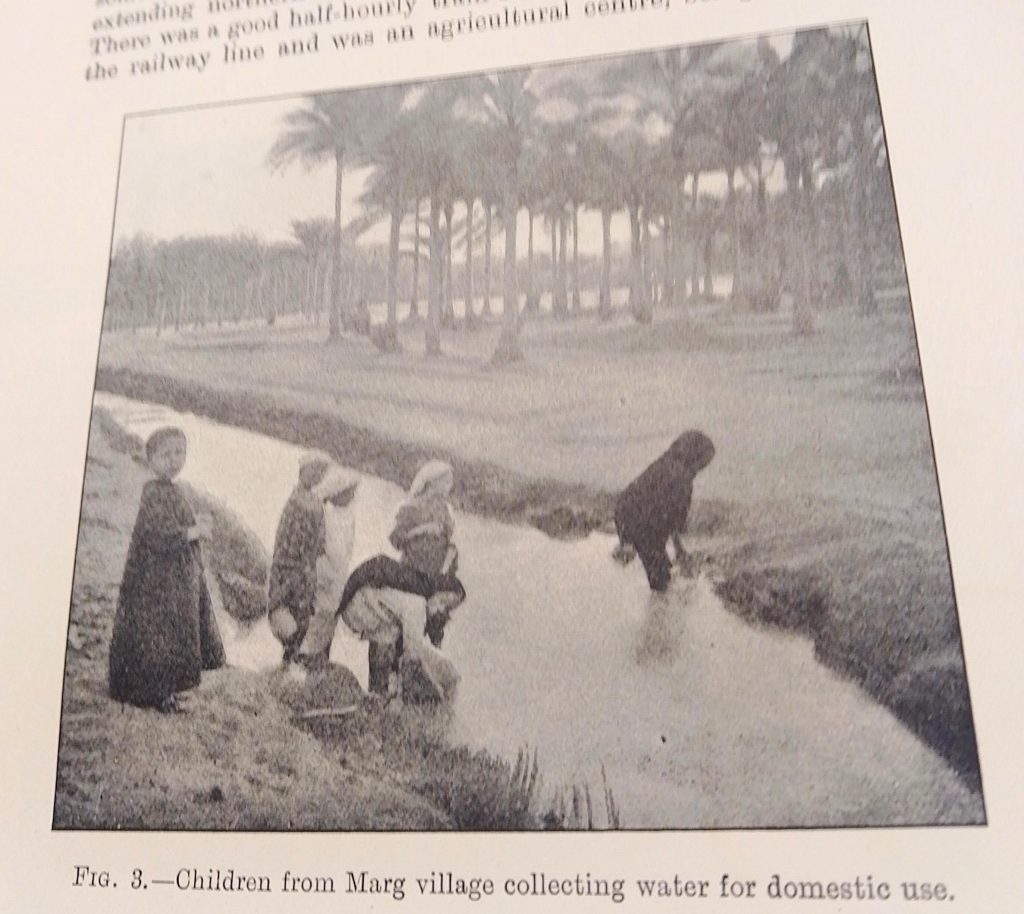

Leiper observed adults and children washing and collecting water to drink from the canals and saw it was likely that schistosome eggs of infected bathers would enter the water in excreta. When Leiper collected water samples he discovered the schistosome eggs were eaten by snails. He further found that the two schistosomes, Schistosoma haematobium and S. mansoni, had different life cycles. S. haematobium utilized Bulinus contortus, a snail with a large body whorl and small spire, as its intermediate host; S. mansoni used Planorbis (biomphalaria) boissyi, a mollusc with a flat, coiled shell.

Laboratory observations of the snails showed schistosome eggs hatching into larvae before escaping into the water. Once the larvae, called cercariae, touched bathers or were collected in drinking water, they bored through the skin and into the blood vessels of their final, human, host where they developed into the worms causing schistosomiasis.

Children from Marg village collecting water (Leiper 1918 : 29)

Women washing in Marg canal (Leiper 1918 : 30)

Having clarified the life cycle of Schistosoma Leiper could now turn his attention to finding ways to prevent the disease. He observed that the larvae survived only 48 hours in water: if the water was stored for more than 48 hours it could be safely used – a simple solution which was to prove of great practical value to the troops. He also recommended eradicating the snail population in their freshwater habitats with poisonous chemicals.

Leiper published the results of his fieldwork in papers in the Journal of the Royal Army Medical Corps, re-published in 1918 (Leiper 1918).

Today there is no cure for schistosomiasis, which affects millions of people in Africa and the Middle East who do not have access to clean water, and it is identified as one of the Neglected Tropical Diseases.

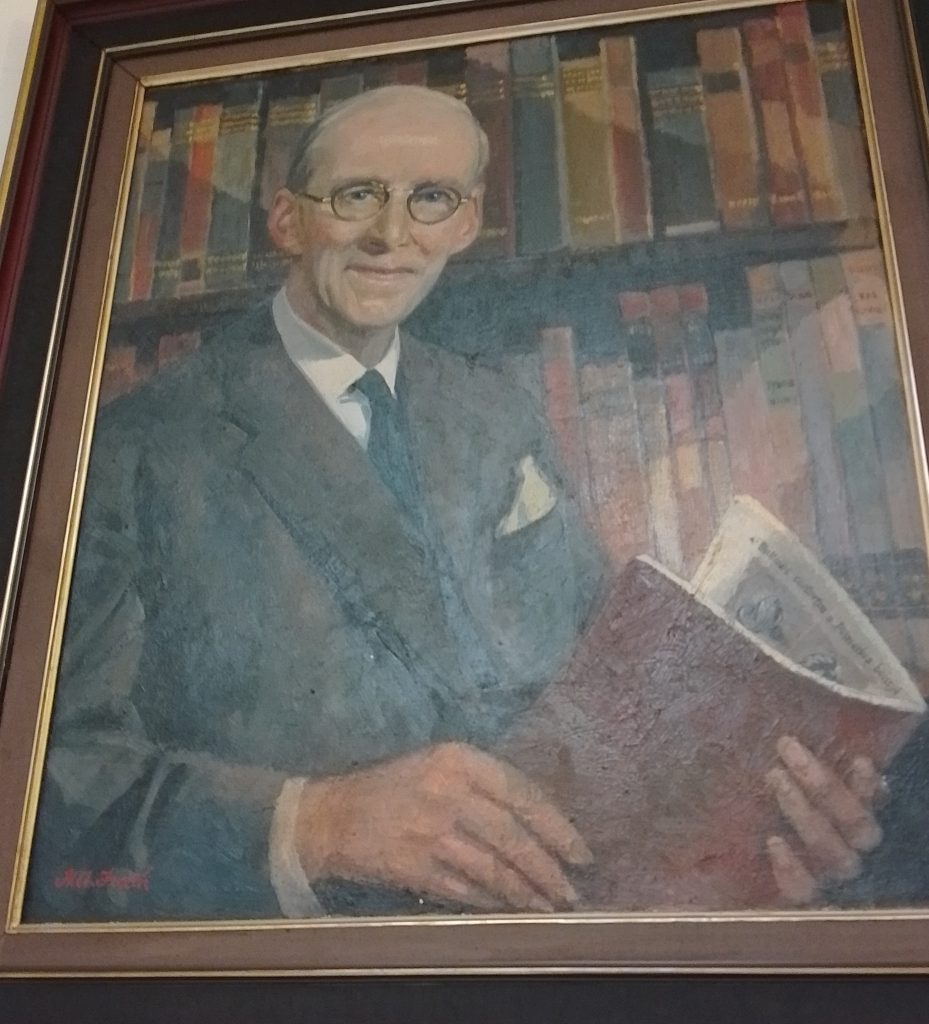

Portrait of R.T. Leiper

Painting of Leiper by Andrew Freeth, RA (1912-1986). The painting shows Leiper seated in front of rows of bookshelves and holding open a book at a page headed, appropriately: “Bulinus … boissyi”.

The undated oil painting, which is held by the LSHTM, is signed H.A. Freeth. The painting measures approximately 105 cm x 85 cm including the frame.

Hubert Andrew Freeth was a British portrait painter who was elected to the RA in 1965. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andrew_Freeth

Leiper’s field work in Egypt in 1915, where he clarified the life cycle of Schistosoma, was one of the highlights of his scientific research. He had joined the School in 1905 and officially retired in 1947. In 1919 he was promoted to professor of helminthology at the School and in 1924 he became director of the department of parasitology. He was not only one of the School’s most eminent scientists but he was also pivotal in directing the School’s future. He facilitated the purchase of its former home, the Endsleigh Palace Hotel, and engaged with the Rockefeller Foundation which part funded the purchase of the Keppel Street site and the present building. He was made a Fellow of the Royal Society of London in 1923.

The inclusion of a sculpture of Bulinus in LSHTM’s ‘gilded vectors of disease’ frieze on the School’s balconies when it opened in 1929 would have acknowledged Leiper’s discovery of the life cycle of Schistosoma and its snail vector, and his role in the building of the LSHTM.

References

Farley, J., 2024. Leiper, Robert Thomson, pp. 280-281, in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography 33.

Leiper, R.T., 1918. Researches on Egyptian bilharziosis. (A report to the War Office on the results of the Bilharzia Mission in Egypt, 1915). Reprinted from The Journal of the Royal Army Medical Corps 25 1915 : 1>, 147>, 253>; 27 1916: 171>; 30 1918 : 235>. London : John Bale. (LSHTM Library MH 1918 : The book was acquired in 1925 and bound in a a dark blue cloth binding).

LSHTM blog of the 1915 Bilharzia Expedition : blogs.lshtm.ac.uk/library/2015/02/10/1915-bilharzia-expedition/

LSHTM Library Rare Books Collection Blogs is an occasional posting highlighting books that are landmarks in the understanding of tropical medicine and public health. The Rare Books Collection was initiated by Cyril Cuthbert Barnard (1894-1959), the first Librarian, from donations and purchases, assisted with grants from the Carnegie United Kingdom Trust. There are approximately 1600 historically important rare and antiquarian books in the Rare Books Collection.

Many of the LSHTM Library’s rare books were digitized as part of the UK Medical Heritage Library. This provides high-quality copyright-free downloads of over 200,000 books and pamphlets for the 19th and early 20th century. To help preserve the rare books, please consult the digital copy in the first instance.

If the book has not been digitized or if you need to consult the physical object, please request access on the Library’s Discover search service. Use the search function to find the book you would like to view. Click the title to view more information and then click ‘Request’. You can also email library@lshtm.ac.uk with details of the item you wish to view. A librarian will get in touch to arrange a time for you to view the item.

Researchers wishing to view the physical rare books must abide by the Guidelines for using the archives and complete and sign a registration form which signifies their agreement to abide by the archive rules. More information is available on the Visiting Archives webpage.