Researched and written by Ian Walden, Archive volunteer.

As we commemorate the centenary of the Gallipoli campaign, the School’s archives remind us that in warfare, the doctor’s struggle to understand and combat disease is as significant as the general’s strategy and the soldier’s courage.

The campaign began on 25th April 1915, when Allied forces, including significant contingents from India, Australia, and New Zealand, landed on the Gallipoli peninsula in present-day Turkey, with the eventual aim of capturing Constantinople, capital of the Ottoman Empire. However, the campaign was a disaster, with Allied advances repeatedly repelled by the well-prepared and rapidly reinforced Ottoman defenders. The death toll steadily mounted, and during the autumn it became clear that troops were needed elsewhere. The last Allied forces were evacuated in January 1916.

The School’s archive material relating to the campaign comes entirely from the papers of Sir Ronald Ross. Already a renowned expert on tropical medicine, in 1914 he volunteered for War service. Initially he was made Consulting Physician to the hospitals for Indian troops in England, but even while in this post he was soon sought out for advice diseases prevalent in the warm climate of the Gallipoli peninsular.

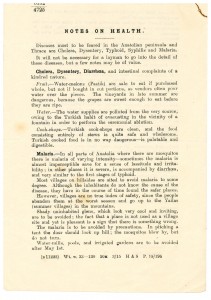

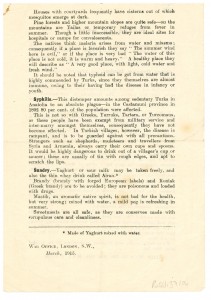

The War Office knew that in most wars, more soldiers died from disease than in battle. In March 1915 they produced a small pamphlet (below) to brief soldiers on the main diseases they could expect to encounter in the broader Anatolia region. Soldiers could protect themselves against cholera, dysentery, and diarrhoea by avoiding local water, not eating cut melons or picking grapes in summer. Malaria infests shadier places, those near water, and low-lying areas, so they were advised to camp on higher ground, where wind would blow mosquitoes past the tent entrance. While local cook-shops and sweetmeats were considered safe, certain local spirits contained opium, and sharing locals’ drinking vessels should be avoided, since the cups’ rough edges could scratch one’s lips and transmit the endemic syphilis infection.

By June, the War Office asked Ross to research and report back on disease in the Gallipoli peninsular in particular. Correspondence and interviews with a variety of medical contacts show that while malaria and cholera were not a huge problem in the area, dysentery could easily become a problem due to polluted water supplies.

By June, the War Office asked Ross to research and report back on disease in the Gallipoli peninsular in particular. Correspondence and interviews with a variety of medical contacts show that while malaria and cholera were not a huge problem in the area, dysentery could easily become a problem due to polluted water supplies.

In July, soldiers with a mysterious new disease were arriving from Gallipoli in the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force base hospitals in Alexandria. Ross was ordered there as consulting physician to aid diagnosis and to advise on treatment, leaving England on 15th July 1915. He later noted that this disease turned out to be “merely Epidemic Catarrhal Jaundice of the milder variety,” but soon after his arrival, a steady stream of soldiers with dysentery kept him in Alexandria.

Many of the hospital doctors were from Britain and other temperate climates, and had little experience with dysentery. They knew that two varieties existed, amoebic and bacillic, and that they must be treated in different ways. However, firm diagnosis was difficult to obtain, and hospital doctors were delaying treatment until diagnosis, by which time patients could be beyond help. Ross consistently recommended early injections of Emetine, an anti-amoeba drug, in all suspicious cases. While some hospital staff were concerned that this drug could itself be toxic if taken for long periods, and blamed some patients’ deaths on heart attacks caused by the drug, a consensus was reached to use it for ten days, and then stop if no benefit was reaped by that stage.

On his return to England, Ross gave a public lecture on the treatment of dysentery, which the Lancet asked permission to publish. On 2nd June 1917, the British Medical Journal published an article about dysentery in Gallipoli. It noted that the war experience had proved that early Emetine treatment reduced the intestinal ulcers caused by amoebas, which in turn made patients less vulnerable to bacterial dysentery, typhoid, and a variety of other dangerous infections. It credited Ross with the programme of early Emetine treatments and concluded that he had “prevented a much higher mortality” among troops in Alexandria.

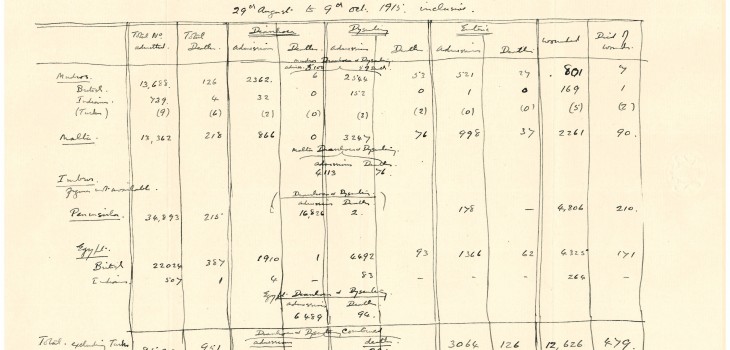

Something of this success can be seen in this table, which shows the number of patients treated in MEF hospitals between 19th August and 9th October 1915. We can see that while field hospitals are dealing with the wounded, those who reach base hospitals in Alexandria and elsewhere are mostly afflicted with disease, of which dysentery is the most prevalent. One soldier in 140 died from dysentery or diarrhoea, a vast improvement on the 30% morbidity seen by Dr. Henry Henry Maurice Chasseaud during the 1912-13 Balkan wars. (Dr. Chasseaud worked at the British Seamen’s Hospital, Dreadnought, the Docks branch of which contained the school that later became LSHTM.) We also see a phenomenon noted by Ross, that Indian troops, who grew up in areas where dysentery was endemic, have developed some immunity and incidence of severe cases leading to death are far fewer than among British (including Anzac) patients.

While this achievement was hailed in the medical press, Ross had other priorities. As he later wrote to his friend Constantine Savas in Athens, “In these troublous times we are obliged to defer those labours which are of real importance to humanity.” The ongoing work of research, vital to all humanity in our common battle against disease, was and is one of many invisible victims of war.

For further information or to study the archives, please email: archives@lshtm.ac.uk