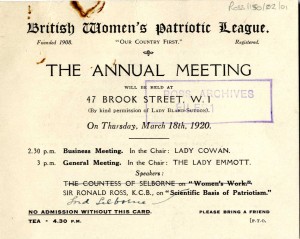

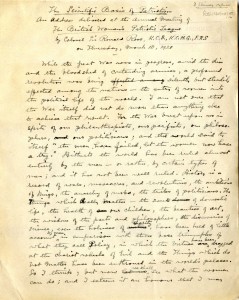

On the 18th March 1920, Sir Ronald Ross delivered a speech at the annual meeting of the British Women’s Patriotic League. He begins the speech by stating that whilst the First World War was in progress a revolution occurred, bringing the entry of women into political life with it. He criticised the leadership of men in the past, and argued that they focused too much on policy and not enough on the health of children, the beauties of art and the wisdom of poets. Here he expressed the widely held belief that men and women are fundamentally different but are of equal importance and intellectual ability. Women’s suffrage and role within society was a key issue of the time, and the role of the First World War in changing the status of women in Britain; still a highly contested issue.

The campaign for female suffrage began in the early 19th century, with the formation of The Women’s Suffrage Committee and the Manchester National Society for Women’s Suffrage in 1866. This early campaign introduced women to modern politics and experience to campaign; a skill later passed onto the next generation of the women’s suffrage movement. In the first decade of the 20th Century, the renowned National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) and the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) worked towards votes for women, using constitutional and militant methods respectively.

At the outbreak of war, the WSPU launched a patriotic campaign; they organised demonstrations and meetings to encourage women to send their sons and husbands to work, they handed out white feathers, which represented cowardice, to men who weren’t fighting, and renamed their paper Britannia in 1915. The NUWSS provided medical relief, found work for the unemployed and set up the Women’s Service Bureau. The East London Federation, led by Sylvia Pankhurst, condemned the war and supported conscientious objectors. They also opened up centres that provided free milk and advice for new mothers, set up restaurants selling cheap meals and continued their social work amongst the poor.

On the 6th February 1918 the Representation of the People Bill became law. This gave the vote to men over 21 (over 19 if they had fought in the war) and to women over 30 if they were on the local government register. 8,400,000 women gained the vote and made up 39.6% of the electorate.