While working on the book display about London the other month, I came across a fairly curious-looking bound volume in the Pamphlet Collection. So, today’s trip into the pamphlet collection will investigate it a bit! Fumifugium, written by John Evelyn and first published in 1661, is now considered one of the earliest works on air pollution. This is not the original 1661 edition, rather a version reprinted some 300 years later in 1961 by the National Society for Clean Air.

We have two of the 1961 reprinted editions. One, the bound volume I mentioned above, has a dedication on the flyleaf to a Dr Charles Wilcocks from A. Meiklijohn. Wilcocks (b. 1896, d. 1977) was a doctor who worked in Tanzania for the British colonial medical service and later for the Bureau of Hygiene and Tropical Diseases, before contracting tuberculosis and moving back to England to continue work for the Bureau there. The Archives hold Wilcocks’ correspondence, which has been described in another blogpost on this site.

The pamphlet’s full title is Fumifugium, or, The inconveniencie of the aer and smoak of London dissipated together with some remedies humbly proposed by J.E. esq. to His Sacred Majestie, and to the Parliament now assembled. Not short on verbosity, the title sets out the subject: the issue of noxious air and smoke in London.

The pamphlet is addressed to the king of England at the time, Charles II. Its argument comes in three parts. First, Evelyn describes the good qualities of London’s air and land, outlines his worries about the smoke, and blames it on industry burning “sea-coal.” Second, he proposes a fix: that trades using sea-coal, chandlers, and butchers move downriver. No further burials should take place within the walls. Third, he suggests improving the scent by planting shrubs around the edges of the city.

The 1961 Foreword praises Evelyn’s supposed clear-sightedness. It claims, “if there had been more men of his kind, then the problems of polluted air would have ended long ago.” This reading might not tell the whole story. Mark Jenner noted how Evelyn’s focus on smoke, stink, and cleansing resembles the metaphors used in contemporary discourse about the Restoration. Though he thinks it is a serious proposal, he argues that Evelyn’s scheme also aligns with the language of Charles’ supporters. It’s also notable that earlier kings had also engaged with the problem of air pollution: William M. Calvert argues Charles I, not forty years previously, had tried to curtail some industrial coal burning in London.

The relationship between air quality and imperial power preoccupies Evelyn. A major part of his argument is that it is unfitting for a city “which commands the Proud Ocean to the Indies, and reaches the farthest Antipodes” to be filled with smoke. He compares the natural air of London favourably with that of Asia, more northerly nations, and “Aethiopia,” a Greek and Latin-influenced term for northern Africa. He claims that those other climates produce worse temperaments, listing their problems as indolence, anger, and tendency towards sickness respectively. The introduction to the 1772 edition, reprinted at the end of the 1961 edition, takes a similar view. It cites the practice of exposure in ancient Greece and Rome and (allegedly) contemporary China, arguing that the deaths of children from smoke pollution should be equally shocking to the reader. In both cases, negative assumptions about other cultures, climates, and practices underpin the rhetoric. Moreover, these are assumptions that the contemporary reader is supposed to share and which support comparisons the reader is to be motivated by in order to improve living conditions in London. The sense of English exceptionalism therefore runs alongside the desire to become even ‘better’ and less like other nations.

This was not the first reprint of Fumifugium by the Society, who had first produced a version in 1933. There was also a separate reprint by the Royal Society in 1930, a copy of which has been digitised by the Wellcome Collection. The preface to this reprint says it was made “in accordance with a general desire reported in The Times for November 29, 1929, when an extension of power stations emitting ‘presumptuous Smoake’ in London was under discussion.” Also, it declares that the Old Ashmolean (a University of Oxford building now housing the History of Science Museum) was no longer fit for purpose due to structural damage from chimney smoke. At the time, it was a laboratory and library. It concludes, “Both books and furnace-flue should be removed from the Old Ashmolean.”

Overall, then, many of the reprints and new editions might have been responses to contemporary debates over air quality. That leads me to wonder whether debate and discussion over air pollution in 1960s Britain contributed to the pamphlet’s reissuing. The Clean Air Act was passed in 1956, four years after the ‘Great Smog’ covered London for five days and was later found to have killed thousands. Though air quality was gradually improving, problems still occurred: this pamphlet was published the year before the 1962 London smog again caused fatalities in the city.

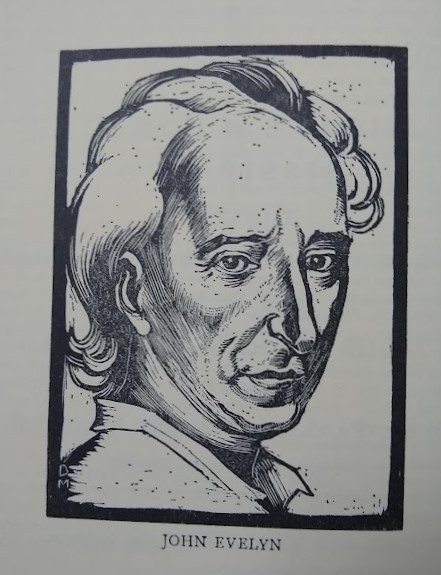

The 1961 volume also includes several evocative printed illustrations. These are absent from other editions, so were perhaps produced for the Society for Clean Air. They include this copy of a portrait of Evelyn, presumably based on either the portrait by Godfrey Kneller, now owned by the Royal Society, or the line engraving after it by Thomas Bragg, a copy of which is now at the National Portrait Gallery.

There are also two illustrations of the city of London, as the artist imagined it was during Evelyn’s time. I’m particularly fond of the little human figures seen scurrying along the street in the second image.

The pamphlet can now be found in the gallery upstairs at the Library at SCL.43 1961. Books on air pollution can be found at the shelf marks SCI-SCP.

Further reading on Evelyn, Fumifugium, and early modern air pollution:

Brimblecombe, Peter. “Interest in Air Pollution Among Early Fellows of the Royal Society.” Notes and records of the Royal Society of London 32, no. 2 (1978): 123–129.

Cavert, William M. “The Environmental Policy of Charles I: Coal Smoke and the English Monarchy, 1624–40.” The Journal of British studies 53, no. 2 (2014): 310–333.

Foster, John Bellamy. “INTRODUCTION TO JOHN EVELYN’S ‘FUMIFUGIUM.’” Organization & environment 12, no. 2 (1999): 184–186.

Hartley, Beryl. “Exploring and Communicating Knowledge of Trees in the Early Royal Society.” Notes and records of the Royal Society of London 64, no. 3 (2010): 229–250.

Jenner, Mark. “The Politics of London Air. John Evelyn’s Fumifugium and the Restoration.” The Historical journal 38, no. 3 (1995): 535–551.

Jones, Gwilym. “Environmental Renaissance Studies.” Literature compass 14, no. 10 (2017).

Sherbo, Arthur. “THOMAS HOLT WHITE AND THE 1772 REPRINT OF JOHN EVELYN’S FUMIFUGIUM.” Notes and queries 27, no. 1 (1980): 57–59.

Other pamphlets on air quality in late 19th and early 20th century London:

Berridge, Virginia, and Suzanne. Taylor. “The Big Smoke: Fifty Years after the 1952 London Smog. Seminar Chaired by Professor Peter Brimblecombe, Held 10 December 2002 at the Brunei Gallery, SOAS, London”. London: Centre for History in Public Health, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine [and] Centre for Contemporary British History, 2005.

Carpenter, Alfred. On London Fogs: Addressed to All Whom They Concern, and Respectfully Dedicated to the London County Council. Croydon: Roffey & Clarke, 1890.

Mortality and Morbidity During the London Fog of December 1952. London, 1954.

Pamphlets on Smoke Pollution, Vol.1, 1885.

Poore, George Vivian. London Fogs, and the Lessons to Be Learnt from Them. London: Sanitary Institute, 1893.