As we’ve already seen in this blog series, the Historical Collection furnishes a huge variety of pre-twentieth-century material that is of value to anyone interested in the history of science or social studies or LSHTM as an institution. The work done to improve catalogue records for this Collection has added valuable information on the book’s binding and material condition, as well as information on past ownership, provenance, and if it contains culturally sensitive material.

In particular, volumes on India appear frequently in the Collection. A previous blogpost investigated the books from the Historical Collection on food and diet in India and how they interacted with the ideals and demands of British colonialism. This post will look at some of the volumes on the natural world in India, and particularly how their writers viewed knowledge about the natural world. As in the previous article, it will also consider how our copies might have entered the Collection and how the ongoing project of adding details on the Historical Collection books’ binding, bookplates, and content enriches their catalogue records on Discover.

Remarks on the uses of some of the bazaar medicines and common medical plants of India, by Edward John Waring

This slim volume is a copy of the text’s fifth edition, published in 1897. It contains an exploration of the medical properties of medicines obtainable in Indian markets or in the reader’s surroundings, as its author puts it, “either purchasable in the bazaars at an almost nominal price, or procurable at the cost of collection, from the road-sides, waste places, or gardens in the immediate neighbourhood of almost every out-station.”

The Prefaces included at the start of the book explain a little more of why and how it was produced. This is especially interesting as it identifies some groups of people who used earlier editions. In his preface to the fourth edition, Waring identifies the first edition’s first users as the “District Vaccinators of Travancore.” Travancore, or Thiruvithamkoor, was a south Indian princely state that forms part of the modern-day Indian state of Kerala. Aparna Nair has written a fascinating article about the history of smallpox vaccination in Travancore, considering how vaccination mediated by a princely state, rather than the direct administration of the British Empire as in many other parts of India, might have differed because of this: from this article, we can see that vaccinators employed by the state were in action from 1807, and those employed by the East India Company a few years prior, both well before the 1860 date of publication of the first edition of Waring’s book. Nair details the gradual growth of the vaccinators’ infrastructure, who numbered 81 by 1899 and served a state with a population of millions. Unsurprisingly, they were expected to travel a lot, hence presumably Waring’s book.

Nair also notes how missionary groups at times contributed to vaccination drives, combining it with their proselytism. This dual role becomes apparent in Waring’s Foreword, as he identifies missionaries as a key audience for his work. He asserts, “I cannot refrain from expressing my firm conviction that the more the principle of Medical Missions — making Religion and Medicine go hand in hand — is carried out, the greater, humanly speaking, will be the success of missionary efforts.”

Waring further singles out “a large army of European and Anglo-Indian officials” who might benefit, and finally the “educated Natives, who, as a class, readily avail themselves of every scrap of knowledge drawn from trustworthy European sources, which tends to throw light on the products and resources of their native land.” The first edition was published as a parallel-text book in English and Tamil, reissued just in Tamil, and translated into Malayalam, according to Waring. While this doesn’t measure actual take-up, it suggests that those responsible for issuing these editions, respectively a missionary society and the Travancore government, anticipated that non-English speakers might be interested in the book’s contents.

Edward John Waring was born in England in 1819 and had died in 1891, prior to this fifth edition’s publication. After studying medicine at Bristol and Charing Cross Hospital, according to his biography by the Royal College of Physicians, he travelled widely under the Emigration Commission and eventually took a role with the East India Company’s Madras establishment, posted at first in Mergui during the Second Anglo-Burmese War, then a residential surgeon in Travancore. The biography suggests he compiled Bazaar Medicines while he was physician to the Maharajah of Travancore. Another biography, Plarr’s Lives of the Fellows of the Royal College of Surgeons, goes into further detail: it argues that Waring’s first posting in Mergui was where he “began his life’s labour as an Indian pharmacologist,” in response to local supply needs. This adds some context to Waring’s Preface and the book’s early use by vaccinators, given that the East India Company had maintained contact with Travancore over vaccination endeavours.

Our volume’s bookplate suggests it was acquired on 11 December 1933, while a date stamp with the date 22 Mar. 1934 might indicate the date on which it was processed and fully added to the collection. Numerous versions are available online, from the first parallel-text edition, to the second, third, fourth, and fifth editions, thanks to digitisation projects in various libraries.

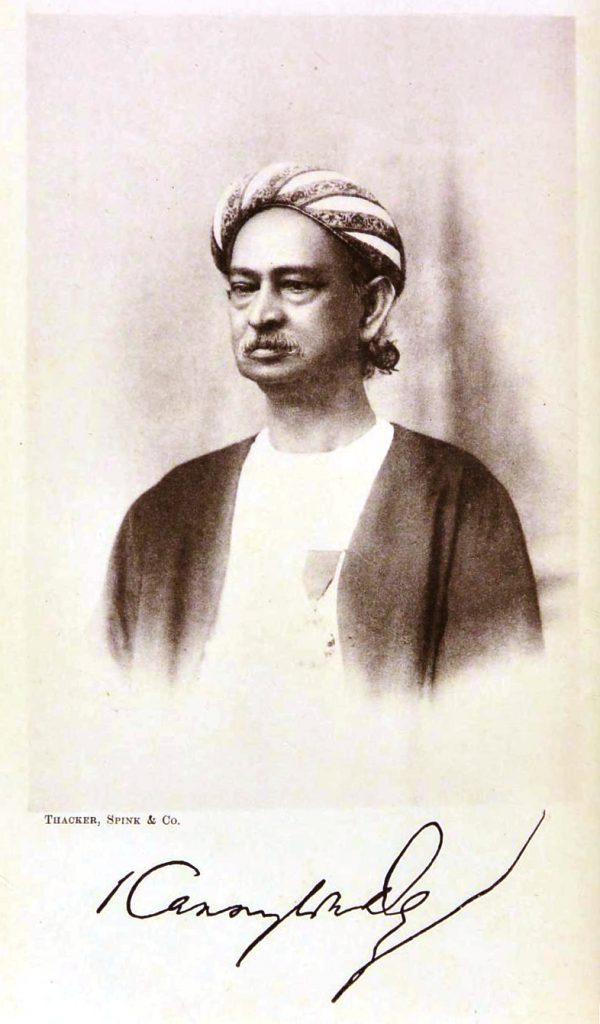

The indigenous drugs of India: short descriptive notices of the principal medicinal products met with in British India by Kanny Lall Dey

This book, a second edition of the text, was published in Calcutta in 1896, after a first edition published in 1867. Kanny Lall Dey, its author, was born in 1831, the son of a Deputy Collector (an administrative role that, under the British Raj, combined revenue collection duties with a district magistracy). Dey studied at the Calcutta Medical College and then began a career as a chemistry professor and a surgeon. The book’s prefatory memoir, penned by Dey’s friend and editor William Mair, describes his engagement with international exhibitions in detail. This information is augmented by a much more recent biographical article by Harkishan Singh. Dey’s contributions were in the field of drugs indigenous to India: according to Singh, Dey was encouraged to reprint the catalogues for further readers and this positive reception planted the seed for his eventual book.

Dey’s stated aims for this new edition were to provide an up-to-date of the most essential information, rather than anything more comprehensive. He also wanted to help to promote the use of what he called “indigenous” drugs in India, responding a trend he had identified among medical authorities in India towards researching and using such drugs. In his review of Indian pharmacology which opens the work, his assessment of the relationship between pharmacological knowledge in India and British imperial influence is as follows:

The gradual progress of Indian pharmacology, the widening and deepening of its influence, and its possibilities in contributing to the health and consequent prosperity of this vast Empire have been in complete sympathy with the gradual development of commerce, medicine, and science in this country. Clear of the mythology and superstition from which, not unlike the medical science of Europe, it evolved, but which lingers still in India, the science has in some measure at least demonstrated the marvellously liberal provision of curative and remedial agents within the reach of the teeming millions of this Empire.

Kanny Lall Dey (1896). The indigenous drugs of India (5th edition). Page xxix.

In other words, Dey felt that India had a rich and longstanding history of medical knowledge of plants, yet he also asserts here that the British Empire had provided an organising and deepening influence on Indian pharmacological research. He presents a narrative of growth and progress, hand in hand with developments in medicine, commerce, and science. Whether pragmatically- or ideologically-driven, here Dey praises British colonial powers as the people most able to promote knowledge about drugs derived from Indian plants.

The rest of the book is an encyclopedia of plants, giving the names of each in different languages, then describing its appearance and its medicinal and other uses. Unfortunately, the book itself provides little information on when it came into LSHTM’s collection. Nonetheless, there is a stamped message on the title page reading “with the publisher’s compliments,” and the name W. J. Simpson written by hand underneath.