The theme of Black History Month this year is Reclaiming Narratives – it is not just about telling stories; it’s about taking control of the narrative itself. It’s about ensuring that Black History is told with the respect, dignity, and accuracy it deserves, we hope to do this with demonstrating the difficulties faced by McCormack Charles Farrell Easmon who studied at the School in 1913.

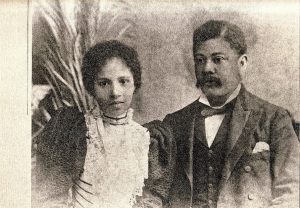

MCF Easmon (1890-1972), was born in Accra, Gold Coast (now Ghana), to Dr John Farrell Easmon, who served as Chief Medical Officer of the Colony in the Gold Coast (now Ghana), and to Annette Kathleen Smith, sister of Adelaide Casley-Hayford a Sierra Leone activist and feminist.

In 1895, Dr JF Easmon proposed to create a training centre in Accra, a West African version of what was to become LSHTM. He was aware that the majority of medical officers dispatched to the colonies did not have the skills and specified knowledge required to recognise and treat tropical diseases. His ideas was to expand the informal instruction that he was providing to medical officers in Accra.

This proposal was ultimately rejected, partly because the Colonial Office feared intercolonial competition. This decision not to offer specialised training in West Africa and the subsequent decision to centralise teaching on tropical medicine in London would affect the lives of many doctors practicing medicine in the tropical colonies, among them Easmon’s own son.

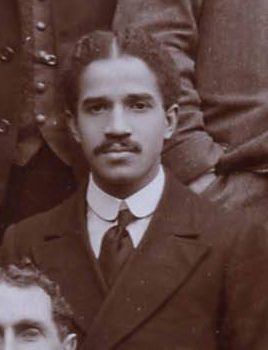

MCF Easmon, with his family, moved to England when his father died in 1900, and studied at Epsom College where he proved his academic aptitude when he was awarded two Epsom College scholarships to study medicine at St Mary’s Hospital Medical School.

Easmon left St Mary’s Hospital Medical School in 1912 where he was awarded a BS (Bachelor of Surgery) and MB (Bachelor of Medicine), and qualified as MRCS (Member of Royal College of Surgeons) and LRCP (Licentiate of Royal College of Physicians). In 1913 at the age of 22, following his time at St Mary’s, Easmon attended the London School of Tropical Medicine where he passed the school’s exam with an impressive 73%.

After completing his studies in London, MCF Easmon applied twice to join the West Africa Medical Staff (W.A.M.S) in its Medical Service and was rejected in both instances as he did not meet the organisation’s criteria of ‘pure European descent’. Instead in 1913, Easmon joined the W.A.M.S as Native Medical Officer in Sierra Leone, a position that was viewed as subordinate to the similar position in the Medical Service. Despite this and experiencing increased racial discrimination – in 1914 a British man shot Easmon in the head with an air rifle – Easmon’s medical career continued to thrive as did his campaign to end racial discrimination in the medical service.

In 1914, Easmon was selected to serve with the British Army as a medical officer in the Cameroons Campaign. Although he was given the rank of temporary Lieutenant in the West African Medical Staff, he was not promoted to a higher rank, despite many of his white counterparts being afforded a promotion. After the war, Easmon returned to England where he continued his studies, including a medical qualification in obstetrics and gynaecology, and continued his career in Sierra Leone undertaking a number of medical posts and publishing a number of articles regarding Helminthiasis and the early history of the Freetown colony.

MCF Easmon retired in 1945, but remained active; he served on a number of government boards and was the first director of the Sierra Leone National Bank. Easmon also promoted Sierra Leone’s culture and heritage when he was appointed chairman of the Monuments and Relics Commission and the first curator of the Sierra Leone Museum, which he founded in 1957. Finally, in 1954, he was awarded an OBE in recognition of his medical service. MCF Easmon died while on holiday in Surrey in 1972.

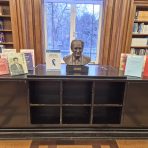

On Thursday 10th October, the Centre for History in Public Health hosted a seminar entitled: Empire, Race, and Medical Achievement: A changing dynamic and the Smith-Easmon medical dynasties by Nigel Davies and Charles Easmon (son of MCF Easmon) which explored the declining fortunes of medical doctors of African descent through the careers of J.F. Easmon and M.C.F. Easmon and the breaking down of racial and professional barriers in the third generation of the Smith-Easmon medical dynasties as experienced by Professor C.S.F. Easmon.