HENRY VANDYKE CARTER (1831-1897) : author of On Leprosy and Elephantiasis, and the artist for Gray’s Anatomy.

Gray’s Anatomy is a classic medical textbook, used by doctors, anatomists and medical artists. Yet, despite Henry Gray’s (1826/27-1861) scholarly text running to 720 pages, it is unlikely the book would have retained its acclaimed position (it has been in print continuously since 1858), were it not for the brilliant 363 text-figures – one on every other page. Credit for the illustrations is due to the subject of this blog – Henry Vandyke Carter. However, it is not for Carter’s artistic ability that he is represented in the Special Books Collection but rather for his book On Leprosy and Elephantiasis (1874), the result of his research in Southern India.

Education and Career

Henry Vandyke Carter was born on 22 May 1831 in Hull, a port city in Yorkshire, England, the son of a marine artist. Although Henry Carter was a naturally gifted artist (as exemplified in Gray’s Anatomy), and doubtless could have taken that career path, to be a physician was his ambition. Being unable to afford to study medicine at university, Henry took the alternative route, taking an apprenticeship to an apothecary in Mayfair in 1848 and studying surgery at St George’s Hospital Medical School (now the Lanesborough Hotel) situated just on the other side of Hyde Park Corner. Henry qualified to work as a general practitioner by gaining membership of the Royal College of Surgeons of England (M.R.C.S.) and an apothecary’s licence (L.S.A.) in 1852. Henry’s goal, however, was to work in hospitals with laboratory facilities for research : in furtherance of this ambition he went to Paris to gain more experience, 1852-53.

Henry secured some financial stability when, back in England, he obtained a studentship in human and comparative anatomy at the Hunterian Museum of the Royal College of Surgeons, June 1853-June 1855. The job was mundane but the great advantage it brought was the opportunity to work under two outstanding British scientists – Richard Owen (1804-1892), comparative anatomist and John Thomas Quekett (1815-1861), microscopist. He was also, until July 1857, Demonstrator in Anatomy at St. George’s Hospital. Whilst carrying on with his jobs, Henry studied at University College Hospital, obtaining his M.B. (1854) and M.D. (1856) from the University of London.

As Henry was not able to find a suitable position in Britain after qualifying, he joined the Indian Medical Service in 1858 as Assistant Surgeon in the Bombay Medical Service. India was not a destination for the faint-hearted. On the one hand there was the lure of the exotic and fortunes to be made, on the other many European lives were lost to tropical diseases they did not understand and reverberations from the Indian Mutiny (1857) were still being felt. Undeterred, Henry Carter purchased the necessary tropical kit, microscope, and books and left England in February and reached Bombay (now Mumbai) in March, 1858. He was 27. Initially he treated soldiers wounded in the Indian Mutiny at Fort George, an army post outside Bombay, before a transfer to the Grant Medical College for Indian students and its affiliated Jamsetjee Jeejeebhoy Hospital in Bombay in 1860. Most of his 30-year career was spent at the College, as Principal from 1881. He retired in July 1888 aged 57 with the honorary rank of Brigade-Surgeon. His personal life in India was marred early by a scandal resulting from an invalid marriage in 1859. He re-married in England in 1890 and had two children. Henry was appointed Honorary Physician to Queen Victoria in 1890. He died of tuberculosis on 4 May 1897 in Scarborough, Yorkshire, aged 65.

Medical Artist

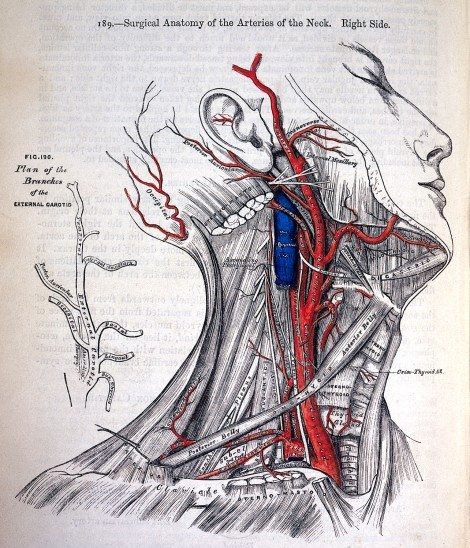

Carter and Gray met when seventeen-year old student Henry Carter attended Henry Gray’s anatomy classes at St. George’s Hospital where his painterly skills had already been employed to design some wall charts. Gray engaged him to illustrate his first book, a specialised work on The Spleen (Gray, 1854), and some reviewers referred to the high-quality of the 64 woodcut figures (Richardson 2008 : 31), although Carter’s name was omitted from the acknowledgements.

Over the next three years, 1855-1858, the pair worked together on the Anatomy; Gray prepared the text while Henry drew the 363 figures, dissecting corpses to better understand and record anatomical structure. Queckett’s training in microscopy was to prove invaluable for when Henry was preparing the illustrations and, later, in the tropics. This time Henry Carter was properly accredited on the title-page of the Anatomy. Gray died in 1861 of smallpox aged only 34.

Scientific Research

All Henry’s research took place in Bombay where many patients presented with diseases that were unknown to European doctors, like the Indian labourers who came to the Hospital with painful swellings on their feet. Henry correctly postulated the cause was a fungus entering the men’s bare feet but he could not prove it (Carter 1861). Later, after confirmation of his theory, the disease was named Carter’s mycetoma.

Leprosy was the most noticeable medical condition seen in the population. Soon after arrival at the Jamsetjee Jeejeebhoy Hospital Henry conducted a major review of the disease (Carter 1863) and, after publication of the 1867 Bombay Presidency census, he extracted data on 8,220 Indian lepers (Carter 1871). From 1873-75 Henry was in Europe principally to consult the Norwegian physician Gerhard Henrik Armauer Hansen (1841-1912), the scientist leading research on the cause of leprosy and care of patients by segregation and treatment. Hansen concluded leprosy was an acquired bacterial infection caused by Mycobacterium leprae and not a hereditary disease as many believed : it is now also known as Hansen’s disease. Henry reported Hansen’s important work in English-language medical literature thereby making it more widely available (Carter 1874a; Carter 1874c).

Shortly after Henry returned to Bombay from Europe the 1877-78 famine struck. Starving patients arrived at the Jamsetjee Jeejeebhoy Hospital suffering from an associated relapsing fever. Working in the Hospital’s Pathology Laboratory Henry identified the cause was a bacterium, Spirillum minus, in the blood. In 1881 Henry was invited to give a paper on relapsing fever at the 7th International Medical Congress in London attended by eminent scientists including Louis Pasteur, Robert Koch and Joseph Lister (Carter 1882).

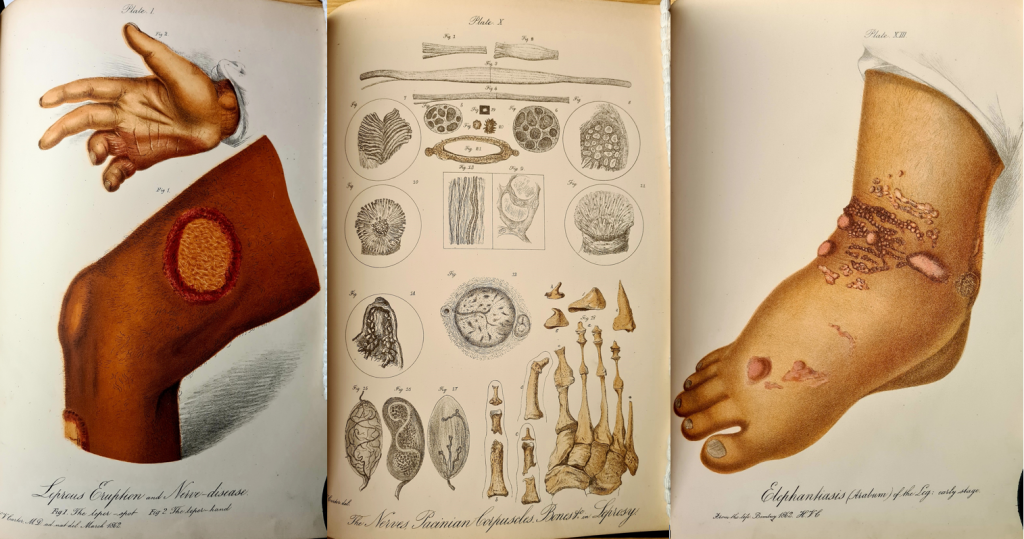

The LSHTM copy of On Leprosy and Elephantiasis with plates

On Leprosy and Elephantiasis with plates was published in London in 1874. The large book, 39 cm in height, was acquired on 30 May 1939, but its earlier provenance is unknown. The Library had it rebound in its present plain, black cloth binding, possibly in 1959. It has nearly 250 pages of text and 15 lithographed plates, many hand-coloured, after Henry’s original drawings. Nine plates portray leprosy patients in India and Norway, three are microscopy studies, and three plates depict elephantiasis. Each plate has a facing page of captions.

In leprosy and Elephantiasis, despite the title, describes leprosy only, except for a single page (p.213) on elephantiasis. Elephantiasis had been linked to leprosy, a theory Henry doubted : “But it is not supposed that this affliction [elephantiasis] is allied to true leprosy” (Carter 1874a: 213). Shortly afterwards Patrick Manson (1844-1922), working in China in 1877-78, discovered elephantiasis was caused by a parasitic worm, Wuchereria bancrofti, that was spread by mosquito vectors.

Select list of Henry Vandyke Carter’s publications.

1861. On a new and striking form of fungus disease, principally affecting the foot, and prevailing endemically in many parts of India. Transactions of the Medical and Physical Society of Bombay 6 (NS) (1860) : 104-142.

1863. On the symptoms and morbid anatomy of leprosy: with remarks. Transactions of the Medical and Physical Society of Bombay 8 (NS) : 1-104.

1871. Report on the prevalence and characters of leprosy in the Bombay Presidency, India, based on the official returns of 1867. Transactions of the Medical and Physical Society of Bombay 11 (NS) : 74-248.

1874a. On Leprosy and Elephantiasis with Plates. London : Printed by George Edward Eyre & William Spottiswoode. v, 213, xxxviii pages, xv leaves, [15] leaves of plates, [2] maps, [1] photographic plate, [1] plan, folded.

1874b. On Mycetoma, or the Fungus Disease of India. London : J. & A. Churchill.

1874c. Report on Leprosy and Leper-Asylums in Norway. With reference to India. London : G.E. Eyre & W. Spottiswoode.

1882. Spirillum Fever: synonyms : famine or relapsing fever as seen in Western India. London : J. & A. Churchill.

References

GRAY, Henry, 1853. On the Structure and Use of the Spleen. London : John W. Parker and Son.

GRAY Henry, 1858. Anatomy, Descriptive and Surgical. … The Drawings by H.V. Carter. The Dissections jointly by the Author and Dr. Carter. London : John W. Parker and Son. 720 pages.

HAYES, Bill, 2009. The Anatomist : A True Story of Gray’s Anatomy. New York : Bellvue Literary Press.

RICHARDSON, Ruth, 2008. The Making of Mr. Gray’s Anatomy. Bodies, Books, Fortune, Fame. Oxford : University Press.

The LSHTM Rare Books blog series is an occasional posting highlighting books that are landmarks in the understanding of tropical medicine and public health. The Rare Books Collection was initiated by Cyril Cuthbert Barnard (1894-1959), the first Librarian, from donations and purchases, assisted with grants from the Carnegie United Kingdom Trust. There are approximately 1600 historically important rare and antiquarian books in the Rare Books Collection.

Many of the LSHTM Library’s rare books were digitised as part of the UK Medical Heritage Library. This provides high-quality, copyright-free downloads of over 200,000 books and pamphlets from the 19th and early 20th century. To help preserve the rare books, please consult the digital copy in the first instance.

If the book has not been digitised or if you need to consult the physical object, please request access on the Library’s Discover search service. Use the search function to find the book you would like to view. Click the title to view more information and then click ‘Request’. You can also email library@lshtm.ac.uk with details of the item you wish to view. A librarian will get in touch to arrange a time for you to view the item.

Researchers wishing to view the physical rare books must abide by the Guidelines for using the archives and complete and sign a registration form which signifies their agreement to abide by the archive rules. More information is available on the Visiting the Archives webpage.