International Women’s day, on 8 March, feels like the perfect opportunity to celebrate the ‘persistent’ spirit of Lady Mary Simpson, one of history’s lesser known figures.

Lady Mary Simpson was the wife of Sir William Simpson, an expert in tropical hygiene who after serving as the Chief Medical Officer of Calcutta was instrumental in the founding of both the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and the Ross Institute. Although not a great deal is known about the life of Mary Simpson it can be assumed that her time in India influenced the invention of a ‘Mosquito Hood’ which she claimed could provide protection for those working in tropical climes.

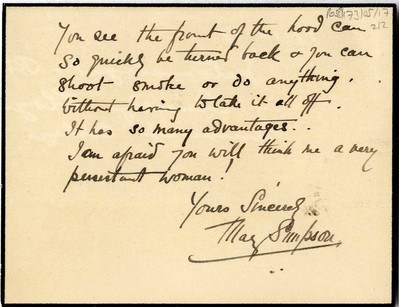

As she outlines in a letter to Ronald Ross on the matter, dated 5. April 1917 ‘the chief feature is that it can be worn at night with comfort when asleep, securing complete protection against the bites of mosquitos’. Furthermore, as Simpson’s letter from 30. June 1917 states ‘the front of the hood can be quickly turned back so you can shoot, smoke or do anything without having to take it off’.

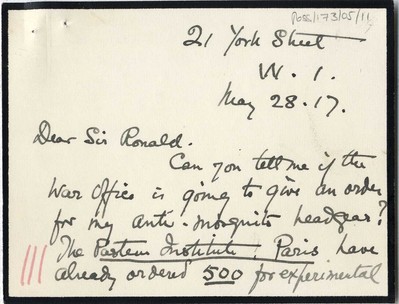

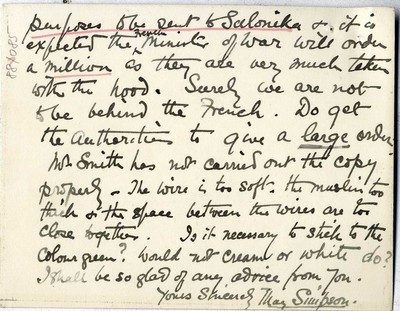

After the outbreak of the First World War Simpson entered into a correspondence with Ross, urging him to use his influence in the War Office, as the then Minister of Malaria, to promote her Mosquito Hood to the British Army. What follows is a forthright exchange of letters. For example, in a letter from May 1917 Simpson refers to an order from the Pasteur Institute for 500 hoods for ‘experimental purposes’, before going on to boast that ‘it is expected the French Minister of War will order a million as they are very much taken with the hood’. She ends the letter with the slightly provocative line ‘surely we are not to be behind the French?’ before imploring Ross to ‘get the authorities to give a large order’.

Ross responds to Simpson on 30. May 1917 by explaining that although he did attempt to promote the hood to his colleagues unfortunately ‘the committee preferred another type’ however they had ‘taken her sample out to the front to compare on the spot’.

In another letter from June 1917, presumably in direct response to a request from Simpson in connection with the hood, Ross states that ‘it would not do for me to give any certificate in connection with such matters, as this would not be allowed, but I can show your nets to people who visit me’.

Clearly disappointed in the War Office’s decision and what she sees as Ross’ lack of commitment in promoting the hood, Simpson, undaunted, sends another letter to Ross on 30. June 1917. She suggests that ‘the committees you mentioned . . . could not have understood the advantages of my invention otherwise they would have favoured it.’ She then, boldly, goes on to express a wish that Ross might ‘induce them to allow me to come and demonstrate and show off all the good points in its favour.’

The letter goes on to further list the many advantages of the invention before, perhaps reflecting on the rather determined tone of her correspondence, Simpson ends with the line ‘I am afraid you will think me a very persistent woman!’

From the tone of her letters and her position as the wife of a highly regarded expert in the field of tropical medicine, it is evident that Lady Mary Simpson enjoyed a degree of social privilege that would have undoubtedly assisted her in her quest to promote the Mosquito Hood. Regardless of her place within society, her determination, strength of character and ‘persistent’ spirit are no less admirable. Her refusal to accept the final word of (presumably) men in positions of power within the War Office – at a time when women’s ideas were rarely heard or taken seriously – is something we can all continue to take inspiration from.

The correspondence between Mary Simpson and Ronald Ross is available in the archives for researchers, please see the archives website for further information on access