The COVID Symptom Study is led by researchers at King’s College London and health science company ZOE. Through the specially designed app, over 4 million people regularly report how they are feeling (whether they feel unwell or not), making it the “the largest public science project of its kind anywhere in the world.” Data from the app, combined with participant swab tests, has allowed researchers to estimate the prevalence of COVID-19 in the UK population and contributed to key findings related to the disease. For example, this study used COVID Symptom Study data to show that loss of taste or smell was a significant COVID-19 symptom, leading the UK government to add it to its main list symptoms.

The study represents a new and innovative approach to conducting surveys, taking advantage of the high prevalence of smart phone use in the population to collect data from millions of people daily. Considering that typical response rates for surveys have been steadily declining over the past 50 years, the fact that the COVID Symptom Study has managed to get millions of people completing a health survey every day is particularly impressive.

I have been reporting on the app since it was launched in March this year – as a budding social researcher myself, I like being able to make a small, daily contribution to both the fight against COVID-19 and health research more generally.

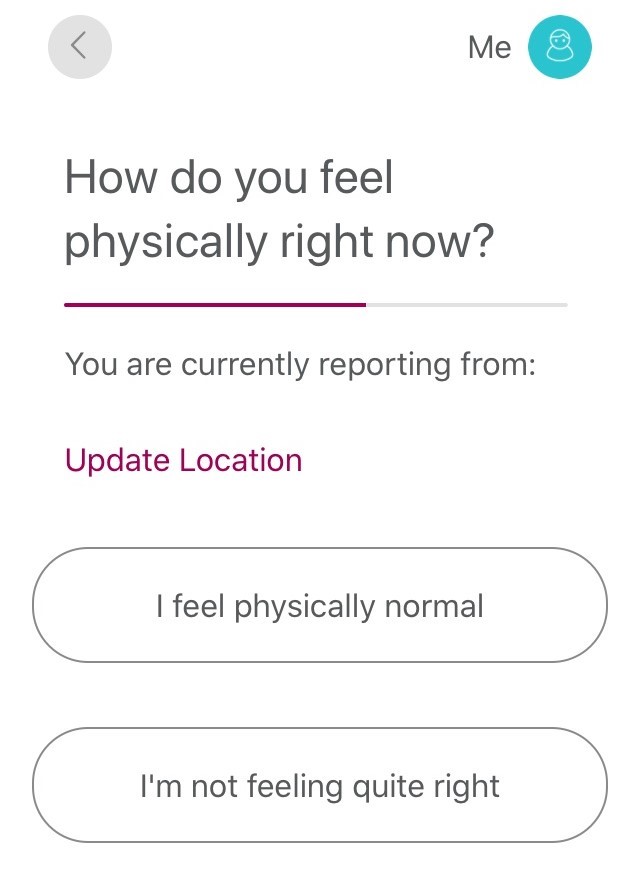

If you have no symptoms, it literally takes about 10 seconds to report. You simply open up the app, and tap the button that says “I’m feeling physically normal”. If you’re “not feeling quite right”, as the app affectionately terms it, you are then asked to report whether you are experiencing a range of symptoms, from commonly known ones such as a high temperature, to less widely known symptoms such as having raised, itchy welts.

Once a week, the app also asks you to report how often you have left the house to go to various types of places, from trips outside involving little interaction with others, like exercising in a park, to trips involving more interaction, such as going on public transport or visiting the pharmacy.

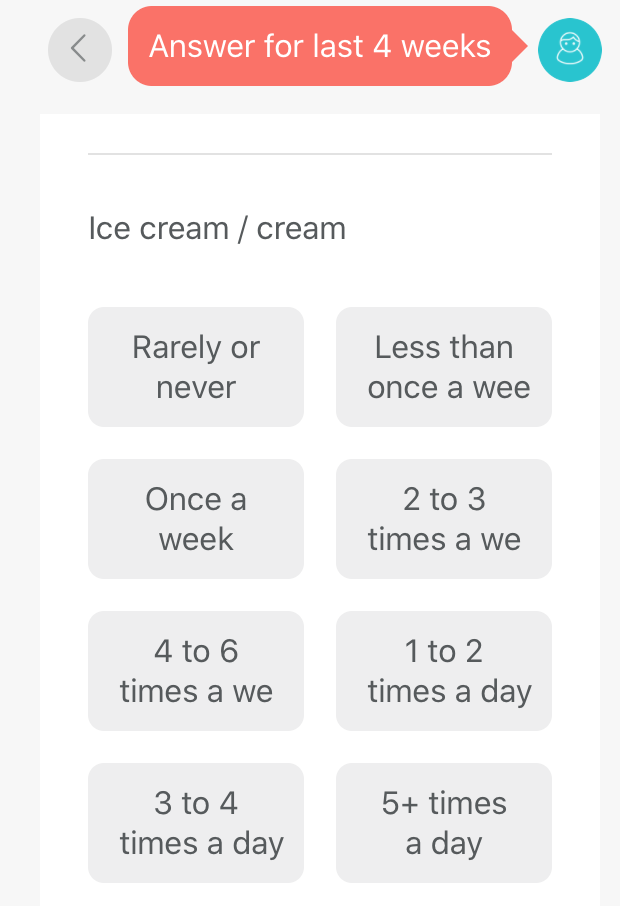

About a month ago, app users were also invited to complete a one-off survey about their eating habits during the previous 4 weeks. Afterwards, they were then asked the same set of questions, but this time asked to consider their eating habits during February. Attempting to give more or less accurate answers to these questions was quite tricky (how much ice cream DID I eat in February?) and highlights some of the challenges in using surveys to research health related behaviours such as eating habits. People often do not accurately report what they actually do, either because they genuinely can’t remember or because they give what they perceive to be a more socially desirable answer.

Another limitation of using a survey which relies on self-reported symptoms to measure the prevalence of COVID-19 in the population is that it does not capture asymptomatic cases. This is why the ONS Coronavirus Infection Survey, which is based on results of swab tests sent to a random sample of households in the UK, consistently gives slightly higher estimates of COVID-19 prevalence than the COVID Symptom Study.

If more people download and regularly report on the app, then better estimates can be generated from the data and clearer insights can be gained into the prevalence of COVID-19 in the population. You can find out more about the study and download the app here.

If you want to know more about the use of survey methodology in health research, the following eBooks are available through Discover:

Abramson, J. & Abramson, Z. (2008). Research methods in community medicine: surveys, epidemiological research, programme evaluation, clinical trials. (6th ed.) John Wiley.

Chander, T. & Durrand, M. (2014). Principles of social research (2nd ed.) Open University Press.

Bowling, A. (2015). Research methods in health: investigating health and health services (4th ed.) Open University Press.