By Alia Carter, UCL Placement Student

As part of my MA Archives and Records Management course at UCL I have been fortunate enough to spend two weeks at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. I was particularly interested in working with the School as I have an interest in Archives that have colonial links.

The School is very interesting in that respect as a blog by Leila Sellers on Decolonising the Archive: the Carpenter Diary points out, “LSHTM was originally founded as an institution for the research and treatment of tropical disease, in an effort to improve the health of those working in the British colonies, which would in turn make the project of empire more profitable.”

Along with other decolonising efforts around the School, the Archives have been doing a lot of impressive work on helping to decolonise the archives.

As part of my two-week work placement here, I have been looking at a collection that was donated by the Department of Infectious and Tropical Diseases, Teaching and Diagnostic Unit.

It belonged to John Lane who was Chief Technician and Curator of Entomology at the then Department of Entomology until his retirement in December 1995. His teaching career spanned from 1960 to 1966 and again from 1972 to 1995. When he died in 2016 the School published an article on the website about him. The collection donated from him is a large and fascinating collection. It has material that would have been from research projects, field work and used as lecture and teaching aids. It consists of world maps, charts, mosquito survey maps, bench aids, lecture slides, and photographs – including fourteen folders of photographs of varied species of mosquito’s and their breeding sites – and collections of illustrations on boards. The material also includes signed material by other notable members of staff or experts in the field including Professor D.S Bertram, H.S. Leeson, W.H Potts, and D.M Minter.

This material was sent to the archive to preserve it for future researchers. It is not used for teaching any more as the material is out of date, for example teaching has moved on from looking at mosquito breeding sites to what different mosquito species actually look like.

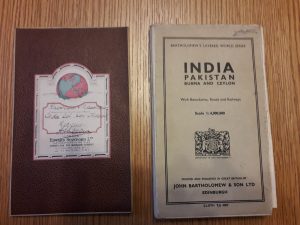

Also, it is important to note that the material is also out of date with regards to a modern audience. The collection has instances of colonial language, with the old colonial place names in maps, out of date country guides and posters – some showing pictorial images of people that could be construed as derogatory, and material that can depict a colonial gaze, for example the colonial gaze in photographs of some of the uncredited and unacknowledged research contributors from India, Sudan and other countries where research was conducted, and the photographs were taken in.

As well as all the practical and technical archival considerations that come up when cataloguing collections – for example – considering original order of the material as it was donated and how to capture this in the cataloguing system, and packaging the material so that it is preserved for future generations, I have also been taking care to catalogue the items with consideration and thought on how a researcher or user will view what is written and presented to them. What would make someone uncomfortable or offended on reading? What instances of these need flagging upfront? What is an old colonial name for a place and how can this be explained and noted carefully and considerately?

It has been fascinating going through the collection and seeing how this can be examined in a real-time, real-life scenario with the many different types of material. The main examples I came across in my time here were old colonial place names in maps like Ceylon, Nyasaland, and Rhodesia and it has been really interesting to consider how to tackle these.

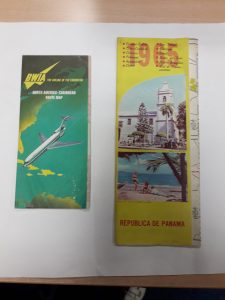

As well as this, it was great to see other items that ended up in the collection. There are folders of plane tickets and old country guides from Tourist boards in the 1950s and 1960s.

There is a lot of work that is involved in trying to decolonise collections, but I feel it is important as it helps ensure that there is appropriate language that feels inclusive to anyone that could come across it, and highlights to users that the Archive practice itself is reflective, considerate, and open to change.

I have learned a lot during my two weeks here. As well as practical skills in surveying a collection, cataloguing, using the cataloguing system Calm, writing notes to advise on basic conservation, packaging items, and working on inclusive and considerate cataloguing language, it has been great to be part of a working Archive service and meet researchers and staff that use the material.

I am incredibly grateful to David Archer, Victoria Cranna, Claire Frankland, Cheryl Whitehorn and the wider Library team for their kind hospitality, support, advice, time, and the freedom given to me to interrogate and examine the archives. I have gained some excellent skills which will be invaluable for me in the future.

For more information on the LSHTM Archives Service, please visit our website at: Archives | Library, Archive & Open Research Services | LSHTM