By Ella Tomlin, Archives Apprentice

Many people set themselves the new year task of starting the new year off on a plant-based diet. Since 2014, the Global Non-Profit organisation “Veganuary” has popularised veganism in mainstream media, running their yearly campaign. However, veganism stemmed from a 20th century British philosophy and associated diet, “plant-based” diets existed long before this across the globe.

If you’ve ever attempted “Veganuary” or explored the dairy-free section of your local supermarket, you’ve likely found yourself face to face with a block of tofu or carton of soy milk. Framed as modern alternatives to meat and dairy, soya’s history across Indonesia, Japan, and China is often obscured. Soya was cultivated and fermented across parts of East and Southeast Asia long before it was mass produced in UK factories. In these contexts, soy foods were not “substitutes” but central components of everyday diets, embedded in local ecologies, agricultural knowledge, and culinary traditions. Fermentation techniques, for example, reflect deep understandings of microbiology long before Western nutritional science named it as such. When British colonial researchers undertook research in these areas, soya-bean consumption found its way to the West, gradually rising in popularity through the 1960’s.

The LSHTM archives ‘Nutrition’ collection contains a variety of recipes, research and media relating to the production and nutritional value of soya-bean products, starting from around 1953. When explored through a post-colonial lens, we can begin to draw out the ways in which colonial power reframed veganism’s history.

Encountering soya through LSHTM’s Archives

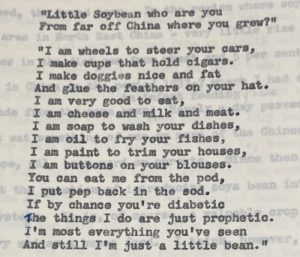

Within LSHTM’s Nutrition collection, references to soy products begin appearing prominently in the early 1950s. These recipes, nutritional analyses and press releases were often produced by British researchers or international organisations operating within post-colonial and developmental frameworks. Some of the earliest mentions of soybeans within the archive come in the form of nutritional research. One report (GB 08 09 Nutrition/18/02/03) nicknames it “the wonder bean” due to enthusiasm for it by medical nutritionists. The bean also inspired a short poem which is spotlighted in the same report. Yet this praise is filtered through Western nutritional priorities, the humble soybean is compared to different vegetables, grains and even meat proteins.

Soy milk, UNICEF and the politics of nutrition

A February 1953 UNICEF press release (GB 08 09 Nutrition/18/17/12) presents “Soy Bean Milk” as a “low cost, high protein” response to malnutrition. Described as one of several “unusual foods” soy milk immediately appears somewhat as an innovation rather than a long-established staple. In the article, United Nations urge the support of soy-farms rather than dairy industries with the aim to “get maximum value from food grown locally in good quantity”, and many of the benefits of utilising the existing soya industry are explored.

In August of the same year, UNICEF advocate for the apportionment to Indonesia for vegetable milk production, (GB 08 09 Nutrition/17/02/02/01) drawing explicitly on existing soybeans consumption practices in the area. Training programmes and the extension of the milk into specific products for child feeding were proposed within the report.

Beyond milk: tofu, tempeh and fermentation cultures

Several articles within the archive begin to explore popular uses of soybeans beyond milk. GB 08 09 Nutrition/17/02/02/01 explores Indonesian “Tahu” (tofu) a curd made from beans that have been soaked for 5 hours, ground and boiled and precipitated with calcium or magnesium salts, and “Tempe Kedele”, a soft, dry, light grey cake made from whole beans, with only the bitter skin removed, which are either fried in oil or cooked with vegetables before eating. In GB 08 09 Nutrition/18/02/04 Japanese foods such as “Natto” (fermented cooked beans used as a side dish and eaten with soy sauce), “Hama natto” (natto mixed with wheat flour, salt and ginger) and “miso” (soybeans fermented with koji) are introduced. Many of these products remain staple in a modern plant-based diet. The techniques discussed within the articles are refined and specific further hinting at the history of the soybean long before British involvement.

Soya’s journey through the LSHTM archives is not just a story of nutrition science. It is a story of cultural exchange, appropriation, and survival. By reading these records critically, we can begin to decolonise both the archive and our understanding of vegan history acknowledging that plant-based futures are rooted in deeply non-Western pasts. Further details on the LSHTM Nutrition collection are available here.