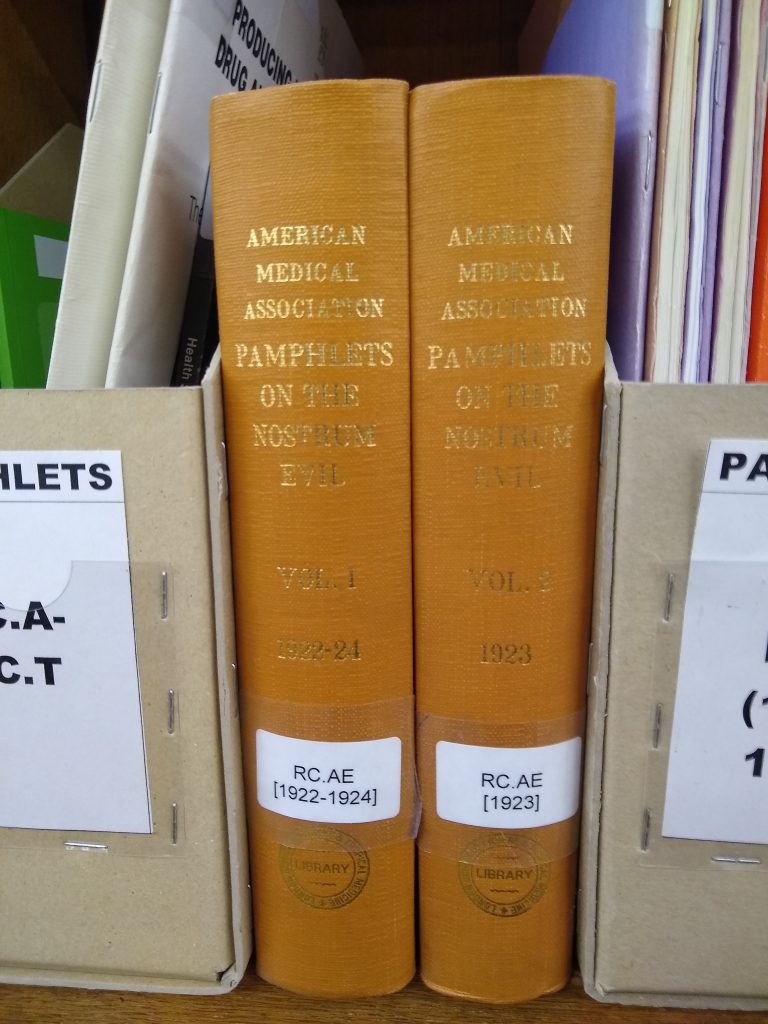

It’s often very peaceful up in the gallery of the main Reading Room. There isn’t any space for desks, just a narrow walkway allowing you to browse the shelves. That means you can pass by a lot of shelving on your way to find a volume, giving ample opportunity for an odd title or shelf mark to catch your eye. That’s what happened to me with these two otherwise unassuming-looking orange bound volumes – the titles, embossed in gold, inform the reader that they contain “Pamphlets on the Nostrum Evil.” Suitably intrigued, I picked them up to investigate…

It turns out that this is a series of pamphlets published in the early 1920s by the Journal of the American Medical Association (amusingly enough, by their “Propaganda Department”) in Chicago. They try to inform a general reader about an astounding variety of quack cures and remedies: these are the so-called “nostra”. You can find them at shelfmarks RC.AE 1922-4 and RC.AE 1923, and catalogue entries for volumes 1 and 2 are on Discover.

Nostra: a brief history

Though fake cures are regrettably still everywhere, the term nostrum is now rather out of fashion. Derived directly from the Latin adjective noster, it would translate literally as “our thing,” denoting the exclusivity of the medicine to its seller. According to Merriam-Webster’s dictionary, its first recorded use in writing in this context comes from 1602. This reference is most likely to a book by Francis Herring, a British physician, entitled The anatomyes of the true physition, and counterfeit mounte-banke wherein both of them, are graphically described, and set out in their right, and orient colours. In a lengthy description of the different traits of a fake doctor (or, in his words a “counterfeite Mounte-Banke”), Herring asserts:

“The greater Part of these Study, and that seriously, the Art of Sophistry, Cousening, and plaine Cony-catching, aduauncing, and setting to sale with Great applause and Concourse, their wit∣lesse Nostrums, which they haue patched together by the marring of two or three good Medicines, to make a third worst of all, feeding the Common People with Toyes, Trifles, Bables, Nut-shels, plaine Chaffe in stead of Wheate…”

Herring, F. (1602). The anatomyes of the true physition… p. 15.

A transcription of Herring’s work is available online on the University of Michigan’s website and makes for fascinating reading. This paragraph suggests that the association between nostra and unscrupulous doctors already existed in the 1600s. It also suggests that people were already lying about qualifications and the efficacy of medicines, and that others were already calling them out on it.

Patent medicines and accusations of quackery

Our pamphlets, published three hundred and twenty years and an ocean away, use the word nostrum because of the precipitous rise of patent medicines in the UK and the USA. Indeed, the name “patent medicine” itself derives from the claims made in advertising to royal endorsement (i.e., “letters patent”) in the 18th century. Patent medicines were widespread and heavily advertised in the USA during the 19th century, as shown in a blogpost on the Smithsonian’s collection.

The early 20th century brought a flurry of works challenging various patent medicines’ efficacy and legality. As a matter of fact, these works use the word nostrum liberally. The earliest contender was The Great American Fraud (1906) by Samuel Hopkins Adams, originally published in Collier’s Weekly. In fact, this publication had an enormous influence on American legislation on the sale of medicines. Adams’ work, according to Bryan Denham (2020), is “widely regarded as a central force behind passage of the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906.” This federal law required manufacturers to name and give quantities of any addictive ingredients, as well as banning the sale of misbranded or adulterated products. Another later example is Morris Fishbein’s Fads and Quackery in Healing (1932).

“Pamphlets on the Nostrum Evil”

There was therefore growing interest among doctors in using print publishing against those they felt were misusing it. This is the context into which we should set our Pamphlets on the Nostrum Evil. In general, books and pamphlets on patent medicine are shelved under shelfmark RC along with books on the pharmaceutical industry.

The pamphlets are divided by subject matter, covering (in vol. 1)

- Alcohol, tobacco, and drug habit cures.

- Cancer “cures” and “treatments”.

- Consumption cures, cough remedies, etc.

- Cosmetic nostrums and allied preparations.

- “Deafness cures”.

- Epilepsy “cures” and “treatments”.

- “Female weakness cures”.

- Mechanical nostrums and quackery of the drugless type.

- Medical institutes (4th ed.).

- Medical mail-order concerns.

In Vol. 2:

- “Men’s specialists”.

- Mineral waters.

- Miscellaneous nostrums (3rd ed.).

- Miscellaneous “specialists”.

- Nostrums for kidney disease and diabetes.

- Obesity cures.

- “Patent medicines”.

- Some quasi-medical institutions.

The articles in these pamphlets are engagingly written. They appeal not only to a reader’s sense of outrage but also to their sense of humour. What’s more, they ridicule the claims made and offer detailed investigations into products and businesses. They also make considerable effort to reproduce some of the offending advertisements to better debunk them.

“Men’s Specialists”

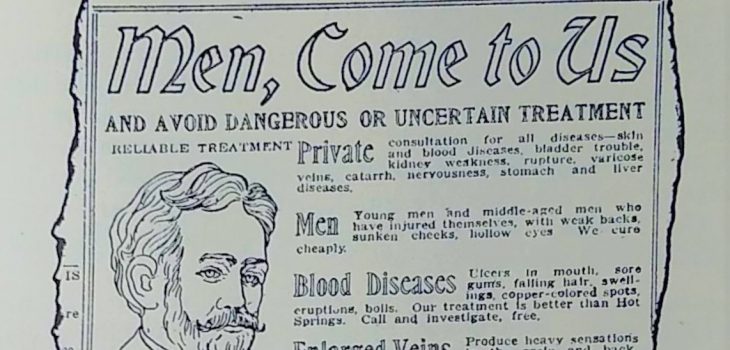

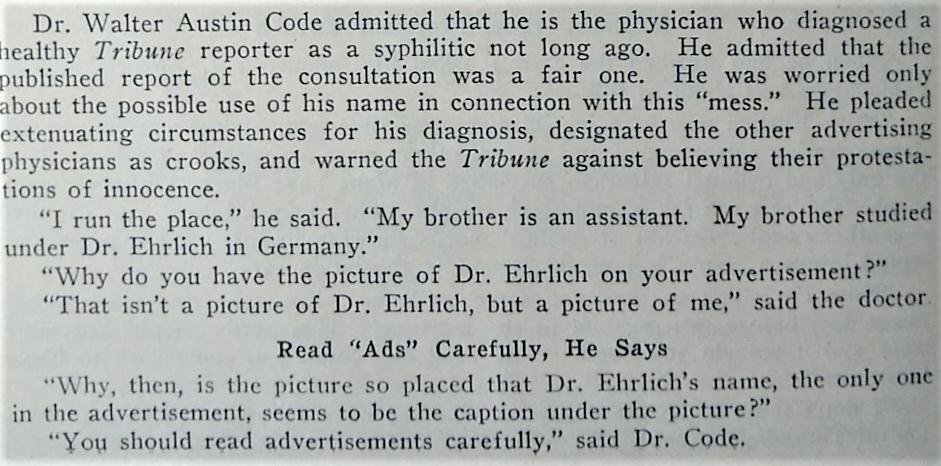

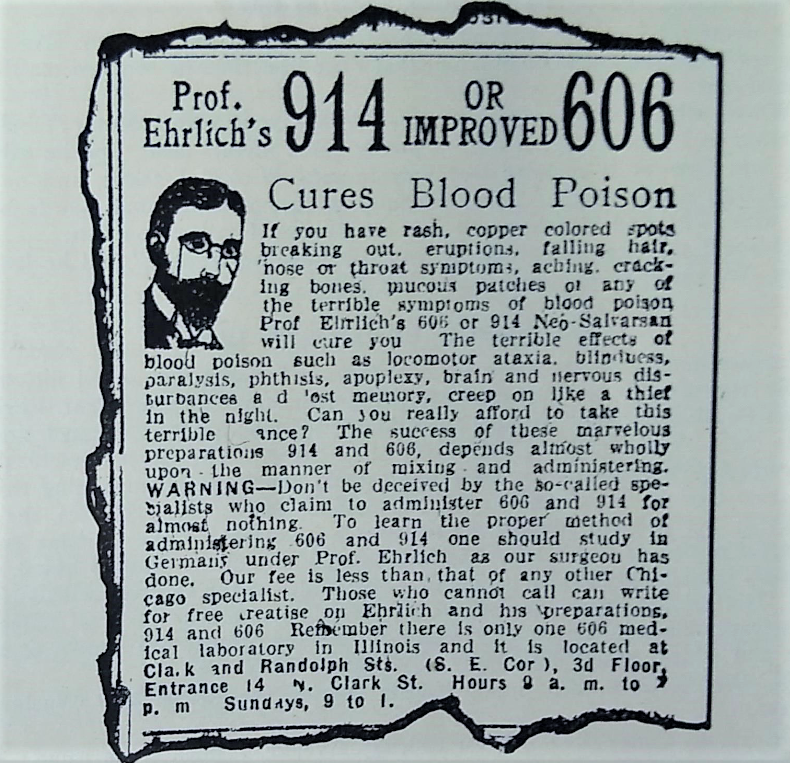

For example, the article on “Men’s Specialists” reprints articles from the Chicago Tribune in 1913, investigating five self-titled specialists in “men’s diseases.” Over nearly one hundred pages, detailed accusations are laid out, reporting patient experiences. Additionally, undercover investigators attended the practices and provided reports. Accusations varied from spurious diagnoses (especially of syphilis) to theft, “seduction,” and medical malpractice resulting in death. In similar fashion and reflecting this variety, the reporting ranges in tone between comic and deadly serious. The contrast in tones is often palpable, as in this argument between an investigated doctor and reporters over his advertising copy:

The advertisement in question:

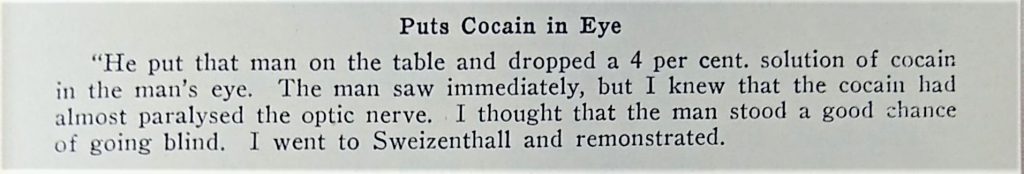

Sometimes, the interventions described sound just plain bizarre as well as dangerous, as with this headline:

None of the language or methods will seem unusual to any reader who’s watched a modern-day scam unravel and get picked apart online. That is perhaps what makes it so interesting. In any case, these debunking attempts have fittingly survived the scammers they sought to unmask. What’s more, they provide evidence for the gradual development and refinement of drug testing, verification, and government oversight in the USA. The greater ease with which information could spread in the age of advertising meant more and more people could be exposed to dangerous pseudoscience. However, that same speed of communication also helped those who sought to counteract the danger, helping to improve public literacy and knowledge of medicine.

References and further reading

Denham, B. (2020). Magazine Journalism in the Golden Age of Muckraking: Patent-Medicine Exposures Before and After the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906. Journalism & Communication Monographs, 22(2), 100–159. https://doi.org/10.1177/1522637920914979

Marcellus, Jane. “Nervous Women and Noble Savages: The Romanticized ‘Other’ in Nineteenth-Century US Patent Medicine Advertising.” Journal of popular culture 41, no. 5 (2008): 784–808. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5931.2008.00549.x

Siff, Stephen, and Sarah Brady Siff. “Muckrakers and Other Manufacturers of Public Opinion on Drugs and Alcohol.” Journalism & communication monographs 22, no. 2 (2020): 164–168. https://doi.org/10.1177/1522637920914981

Teal, Adrian. “Quacks and Hacks: Georgian Medicine and the Power of Advertising.” The Lancet (British edition) 383, no. 9915 (2014): 404–405. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60141-0

Torbenson, Michael, and Jonathon Erlen. “A Quantitative Profile of the Patent Medicine Industry in Baltimore from 1863 to 1930.” Pharmacy in history 49, no. 1 (2007): 15–27.

Valuck, R. J,, S. Poirier, and R. G. Mrtek. “Patent Medicine Muckraking: Influences on American Pharmacy, Social Reform, and Foreign Authors.” Pharmacy in history 34, no. 4 (1992): 183–192.