For the second in our Decolonising the Archive series – we are re-examining Roads to Africa, a film documenting a 1936 field trip to East Africa, by the entomologist Major H.S. Leeson and his then assistant David Gillett. The men were in East Africa to conduct research into malaria, and Leeson would go on to make a significant contribution to malaria prevention throughout the world. The film is a rare historical item, showing the men collecting samples for research, as well as interactions with people local to the places they visited. The footage is accompanied by a narration from Gillett, added in 1995. This blog will look closely at Roads to Africa, analysing the material from a decolonising perspective in order to challenge some of the long held perceptions and assumptions associated with the colonial era that continue to inform contemporary social discourse.

To some extent the film could be interpreted in a positive light. From the beginning of the footage there is a sense that the researchers are attempting to actively engage with the people they meet and there is an effort to represent them in the film – rather than simply document the colonial experience. For example, at the start of the film, Leeson employs two local Ugandan assistants. Kaddu who acts as ‘mosquito collector’ and interpreter, and a cook named Ezra or ‘Ezira’ as Gillett insists on calling him in reference to the way his name is pronounced locally. The very fact that these two men are referred to by name, goes some way to acknowledge them as individuals and could be viewed as progress when compared to the anonymous crowds briefly referred to in the Carpenter Diary. However, Gillet’s deliberate mispronunciation (as he sees it) of Ezra’s name as ‘Ezira’ demonstrates the superior attitude of the white men in relation to their Ugandan assistants – a little ‘in-joke’ about the cook’s inability to ‘put two consonants together’ that even 60 years later Gillett is clearly still amused by.

This superior attitude is evident throughout the film. An early scene shows the two Ugandan men packing the car, while Leeson, wearing those hallmarks of the colonial era – safari suit and pith helmet – supervises. The travel arrangements, as described in Gillett’s voiceover, highlight the inequality implicit within the relationship between the men. Gillett and Leeson sitting in relative comfort in the front of the car, while Kaddu and Ezra are crammed in alongside the luggage in the back. Gillett goes someway to acknowledge the unfairness of this, wondering in the commentary ‘how they survived, cramped in this position, crowded like this, I don’t know’, before going on to seemingly satisfy his own conscious by declaring that ‘they didn’t seem to mind’. Whether or not Gillett ever asked either of the men if they did mind their uncomfortable mode of travel is unclear. The fact that neither Kaddu or Ezra appeared to voice their discomfort could be interpreted as a manifestation of the imbalance of power between the British and Ugandan men, rather than a quiet acceptance of the situation.

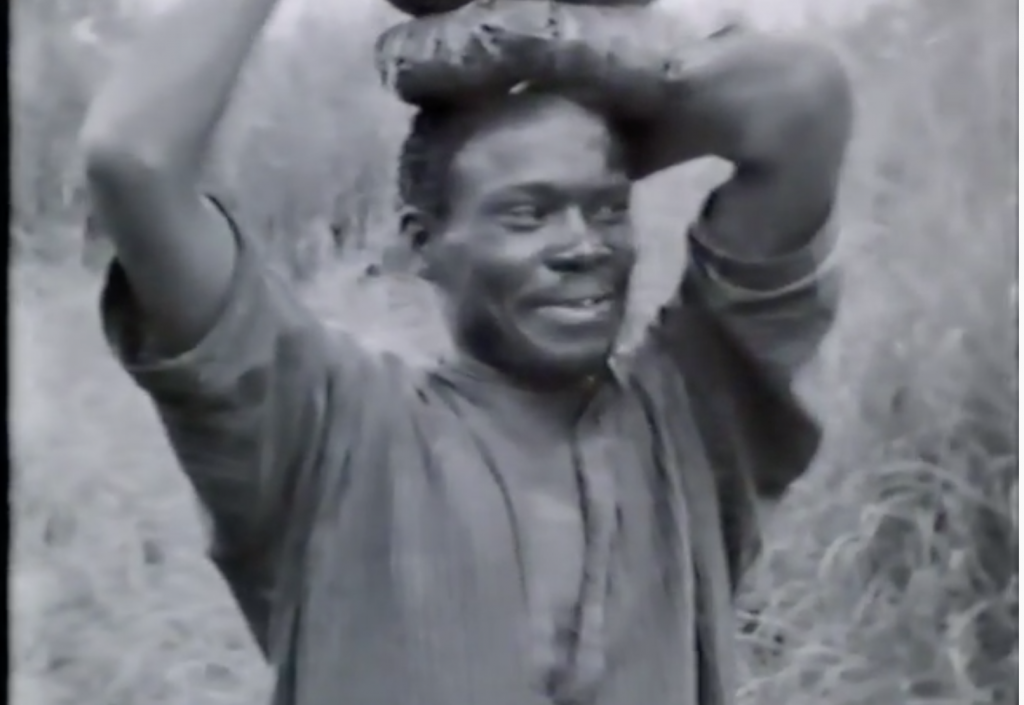

Much of the footage from the film shows the researchers visiting villages and interacting with the local population. Once again, this attempt by Leeson and Gillett to capture these interactions on film can, to a degree, be interpreted positively. It could be argued that such footage makes the lives of colonised people visible within history. However, despite these efforts the limitations of the film are all too apparent. For example, in one scene the camera focuses on an East African man, in non-western dress. Gillett’s commentary informs us that ‘whenever we saw something interesting we would stop and film it’. There a is a sense – highlighted here, but replicated within the many interactions caught on camera by Gillett – that the man has not given his consent to be filmed. Denied the right to exercise his own agency, in this instance, the anonymous man on camera has been reduced to an object by the researchers. Gillett’s use of the word ‘something’ emphasising the idea that, from the colonial perspective, this man is simply an interesting part of the scenery, rather than a person in his own right.

It can be argued that Roads to Africa renders visible the presence, and in some instances the individual identities, of people colonised by the British in early twentieth century Africa. However, on closer inspection, the nature of these interactions between colonised and coloniser only serves to further highlight the power imbalance between the two groups. Throughout the film Gillett and Leeson never move beyond treating the people they encounter with a kind of detached curiosity, and there is little or no attempt to understand or communicate with them on an equal footing. Even the claim, made by Gillett, that the local people were ‘as interested in us as we were in them’ – which could be viewed as an attempt to redress the balance between the local people and the colonial researchers – is somewhat undermined when Gillett uses the same phrase to describe the mutual curiosity between them and a giraffe they come across. This once again, highlights the fact that to the researchers, the people, animals and environments they encountered as they travelled through Africa were all similarly part of a romantic notion of what Gillett calls ‘life in the raw’.

Beyond the assumptions made by Gillett within the narration regarding the reactions of people they met, we have no real sense of the true feelings of the Ugandan people to the colonial presence. For example, aside from being ‘interpreter’ and ‘cook’ respectively, who were Kaddu and Ezra? How did they feel about their British employers? Were the local people Gillett and Leeson encountered really ‘always cheerful’ as Gillett asserts or did they resent the intrusion of the British men, violating their privacy by insisting on filming them? Almost a century later, these questions are difficult to answer. However, even by posing such questions we begin to disrupt the colonial narrative and reject the assumptions made about the lives and experiences of colonised people. In this context, the ‘cheerful’, ‘interested’ people broadly defined by Gillett within the film can instead be re-framed as individuals with thoughts, feelings and identities of their own.