At 31 years old MacCallan was working as an unpaid chief clinical assistant when he was offered a position to operate Egypt’s first travelling ophthalmic hospital (TOH). The post was funded by a £40,000 trust established by the philanthropist and financier Sir Ernest Cassell. Cassell had financed the Aswan (Low) Dam and had been shocked by the extent of the suffering caused by ophthalmia in the local population.

MacCallan’s role was to implement the objectives of the Trust and his letters reveal the many challenges he faced in the early days. The first TOH camp consisted of ten tents with a kitchen and stores housed in mud brick buildings. It was set up at Menouf, a town equidistant between Cairo and Alexandria. Writing home, MacCallan recorded that he had to contend with heat, flies and ‘mosquitos as big as sparrows’. Yet the first hospital was a great success treating 6,157 patients and undertaking 615 operations in 3 months.

By 1912, eight hospitals designed by MacCallan had been built with money raised through a combination of public subscriptions and donations from private benefactors. The hospitals were part of an ambitious plan to build a permanent eye hospital in the capital of every province of Egypt. Later, MacCallen was instructed by Field Marshal Kitchener to undertake research into ankylostomiasis and bilharzlosis. A further five further TOH’s were set up to focus on these infections.

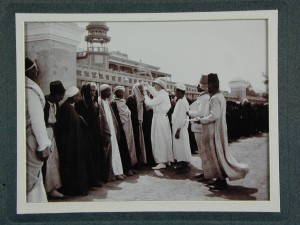

Photo from MacCallan photo album, courtesy of the MacCallan Family

Scenes of the early TOHs and of the war years are captured in the many photographs taken by Arthur. During the First World War, the TOH’s were converted into military hospitals to treat sick and wounded troops from Suez, Gallipoli and Salonika campaigns.

Arthur’s letters reveal that in his early days he did much soul-searching as to whether or not he should stay in Egypt. Yet by the time of his final departure in 1924 there was over 20 permanent ophthalmic hospital units, including TOH’s, which bear testimony to his dedication and determination. Arthur was awarded the CBE (1920) and Order of the Nile (1924) for his services to ophthamology. In 1931 his students and patients erected a bust in his honour at the Memorial Ophthalmic Laboratory at Giza where it can still be seen today.

MacCallan’s Ophthalmic Hospitals in WWI

By 1915 Arthur Ferguson MacCallan had already established an infrastructure of permanent and travelling ophthalmic hospitals across Egypt. In January 1915, recognising the flexibility and the skills offered by the hospitals, the War Office began to commandeer them for the War Effort. They would go on to treat thousands of soldiers injured in the First World War’s Middle East campaigns.

The first to be converted were three travelling hospitals (TOHs) which became clearing units in Ismailia and Suez. These first temporary units treated wounded Turkish prisoners captured that Spring, and in April further TOHs were transferred to Zagazig on the request of the French authorities. The versatility and flexibility of TOHs allowed them to change location rapidly without compromising their capabilities. The Zagazig hospitals provided essential accommodation for the Senegalese troops wounded at Gallipoli.

Arthur MacCallan’s personal involvement in the War began when he proposed an ambitious plan to create a well-equipped, under-canvas, general hospital at Alexandria. His plan was quickly approved by the Surgeon-General and within two weeks the general hospital was operational at Glymenopoulu Bay where it treated a variety of conditions including trachoma. At first it provided 200 beds but that later increased to 400 and later still to 550. Arthur described the hospital with pride as:

fully equipped with the necessary surgical instruments by the central stores of the department of Public Health [including] a complete installation of electric light, X-rays, and telephones. […] With the sea on two sides, the western and the northern [it was] probably the most healthy place in the whole of Europe.

Writing after the War, Arthur noted that between 1916 and 1918 there had been over 30,000 eye cases amongst the troops, and that an enormous numbers of exhausted and underfed Turkish prisoners with very little resistance to diseases such as pellagra, enteritis, dysentery and broncho-pneumonia had also been treated at the temporary hospitals.

MacCallan received many plaudits for his organisational achievements during the War, including a letter of thanks from Violet Asquith, Prime Minister Herbert Asquith’s daughter. He was awarded three war medals: the Star, the General Service Medal and the Victory Medal 1914-18.