In those parts of the world with a written language, the first organisms in the natural world to be studied, documented and figured were plants in recognition of their economic value in agriculture, nutrition, health and well-being. In Europe these herbals, as they are called, were hand-written in Greek and Latin and often included magnificent illustrations. After the invention of printing in the 15th century herbals had a wide circulation in print in the classical languages before being translated into English and other languages. From the 17th century the herbals of the ancients were superseded by new books which sourced medicinal plants growing naturally in the country. At the same time poor people, who could not afford a doctor, used healing products derived from the local flora. The Chelsea Physic Garden opened in 1673 and, later, the Royal College of Physicians, creating gardens of plants with links to medicine (both open today).

On the Indian subcontinent, with its abundance of medicinal plants, drugs derived from plants formed one of the components of ayurveda, the traditional Hindu medical system. It continues to be one of India’s health care systems. Sanskrit records of plants can be traced as far back as about 3000 years. In the nineteenth century some East India Company physicians took an interest in traditional Indian medicine. One, Whitelaw Ainslie (1767-1837), a Madras surgeon and author of two books wrote “The first book in English on the materia medica of India, and a pioneering work in the field of Indian medical history. The specific purpose of his book was to make indigenous remedies available to the British Army, thus reducing its reliance on expensive imported drugs; however, his larger purpose was to bridge the gap between the medical cultures of Europe and Asia” (https://www.historyofmedicine.com/author/all/#whitelaw-ainslie) (Ainslie 1813; 1826).

Interest in Indian plants by the British continued and intensified throughout the 19th century. Botanical specimens were collected on a massive scale with particular emphasis on plants of economic importance. In 1801 the East India Company opened the India Museum in Leadenhall Street in the City of London to house the material. When the Museum closed in 1879 the herbarium was transferred to the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew where it formed the basis for the Museum of Economic Botany. Besides specimens of timber and spices the collection came with plants identified as having medicinal properties used in ayurvedic medicine. Today these specimens and associated labels and data are being digitized by staff at Kew (Messenger 2023)

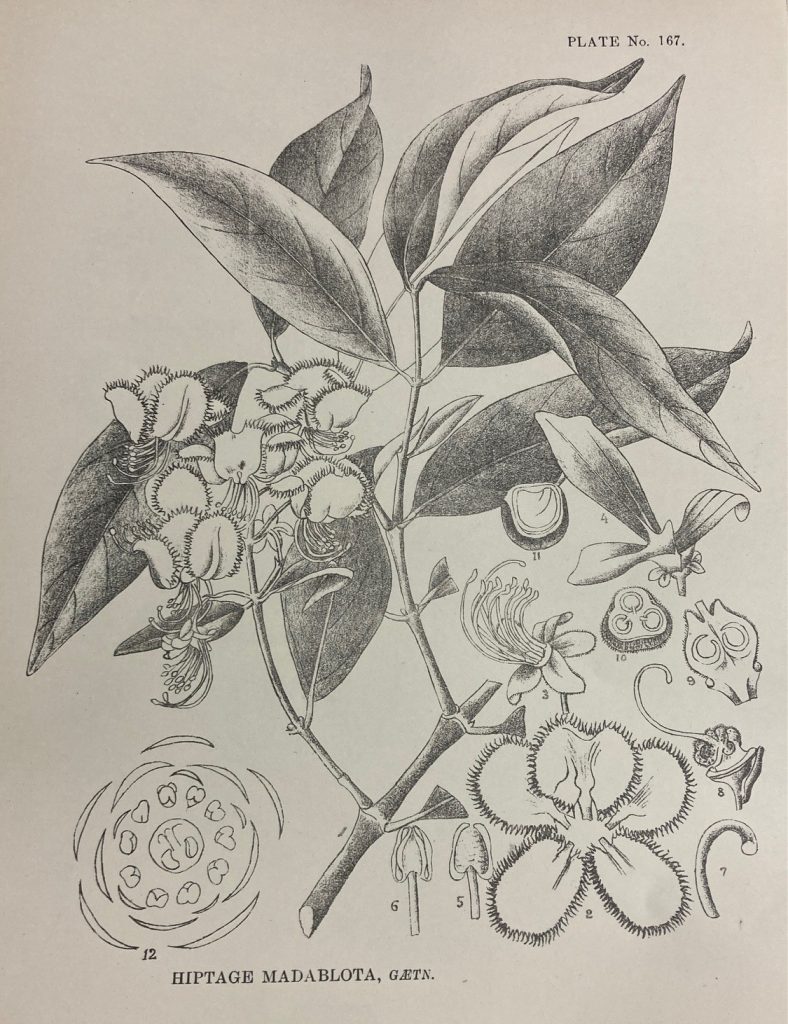

Neither of Ainslie’s books was illustrated and it was not until 100 years later that Kirtikar and Basu published Indian medicinal plants containing more than 1000 black and white plates of plant figures. These visual images were an important addition and helped to clarify and augment the text to aid species identification.

Title page of Indian medicinal plants. Vol. 1, 1918.

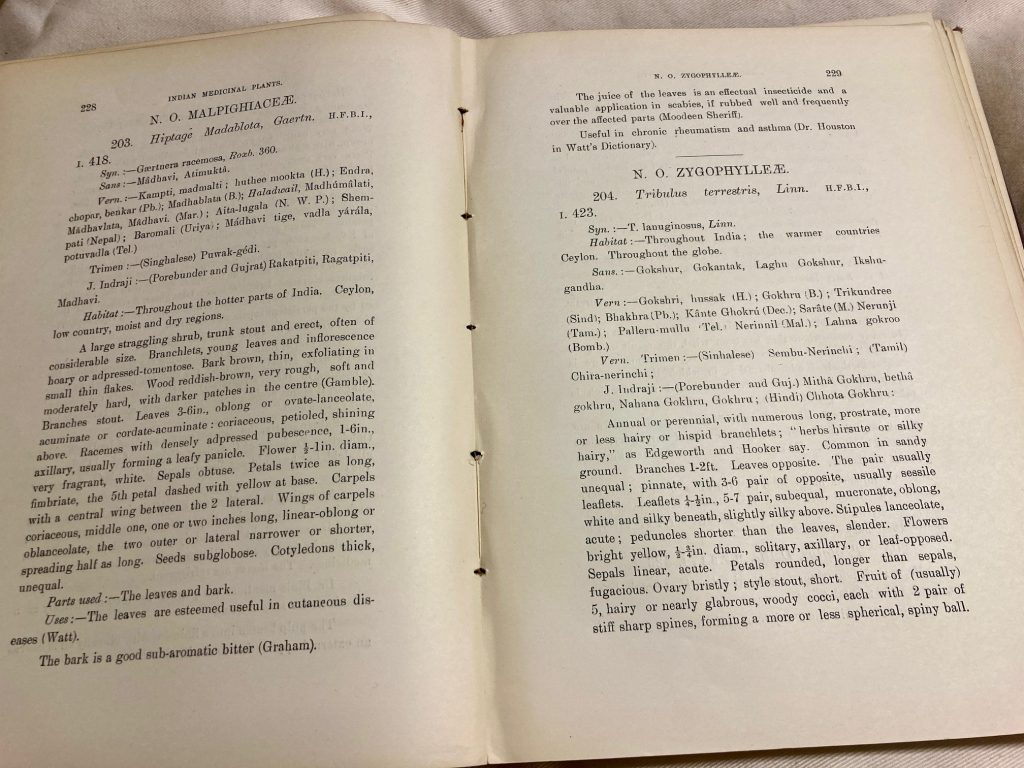

Text description of Hiptage Madablota (203)(Text, Vol. 1, pp. 228-229)

Plate of Hiptage Madablota (203) (Atlas, Vol. 1, plate 167)

The current name for this plant is Hiptage benghalensis, often just called hiptage. (Hiptage Madablota is a synonym). For more information about this plant see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hiptage_benghalensis

Lieutenant-Colonel Kanhoba Ranchoddas Kirtikar (1849-1917) F.L.S., I.M.S., was an army surgeon and botanist.

Kirtikar and B.D. Basu c. 1917

He was born in Bombay and studied medicine in Bombay. In 1874 he visited England and became a member of the Royal College of Surgeons in 1876. He was one of the few Indians who joined the Indian Medical Service and served in it until 1881 when he became a civil surgeon. From 1886-1904 he was Professor of Anatomy, Botany and Materia Medica at Grant Medical College – the same college where he had been a student. He was also appointed Health Officer for Bombay. After retirement he pursued his botanical interests that culminated in the publication of Indian medicinal plants. Although ill-health prevented Kirtikar from finalizing the work, and he died on 9 May 1917, it was published in 1918 by his co-author B.D. Basu (Anonymous 1.)

Major Baman Das Basu (1867-1930) was an Indian army physician, botanist and nationalist.

After studying medicine in Lahore, Basu qualified in England and joined the Indian Medical Service. He was posted to the Bombay Presidency where he served from 1891-1907 rising to the rank of Major. Afterwards, he became a civil surgeon in Ahmednagar, Maharashtra State, Western India. Basu was a fervent Indian nationalist with beliefs that conflicted with his work for British imperialists and he resigned to join the Panini Office in Allahabad where he published several books including My sojourn in England (1927). He built up an extensive personal library to which Lieutenant-Colonel Kirtikar bequeathed his own collection. In 1920 Basu donated Kirtikar’s herbaria and botanical books and journals to Calcutta University. Basu was president of the 9th All-India Ayurvedic conference. He died on 23 September 1930. (Anonymous 2.)

A third author is named on the titlepage of the text volumes by initials only – I.C.S. The identity of this person has not been determined and it is thought to refer to someone in the Indian Civil Service with a knowledge of botany.

Kirtikar and Basu’s Indian medicinal plants is a huge compilation comprising two volumes of text and more than 1000 plates of plants in four volumes. Although the book does not have an alphabetic index to plant names, Vol. 1 has a list of species names under the plant family to which it belongs. Each species is referenced by a unique number, text page and plate number (Vol. 1. Table of contents, pp. xi-xxxi).

To produce a book of this magnitude the authors carried out extensive searches of the earlier literature and went to great lengths to illustrate every species : “most of the illustrations … are reproductions from those in various works on Indian botany … of such well-known masters of the subject, as Rheede, Roxburgh, Royle, Burman, Brandis, Beddome, Griffiths, Wallich, Wight …” (Preface pp. vi-vii). Other plants had to be drawn from nature by Kirtikar, himself a good draughtsman, and an artist in Bombay (Preface, Vol. 1, : v) and by Indian artists working in the Herbarium of the Botanic Garden, Calcutta (Preface : viii). The drawings were printed by lithography on large lithographic stones and art paper imported from Europe. The cost of this mammoth publication was supported by a donation of 10,000 rupees from the Maharaja Bahadur of Cossimbazar, the Hon’ble Sir Manindra Chandra Nandy, K.C.I.E. (Preface Vol. 1, p. x).

Each plant is illustrated by several line figures showing the typical appearance of leaves, flowers, fruits, and including some dissections. Line drawings show the diagnostic features important for identification and are better for this purpose than photographs.

The LSHTM Library copy of Indian medicinal plants was acquired at the time of publication by the Tropical Diseases Bureau on 21 November 1919. Later, the Bureau’s Library was integrated into the LSHTM Library. The book is still in its original publisher’s maroon cloth binding.

References

AINSLIE, Whitelaw, 1813. Materia medica of Hindoostan, and artisan’s and agriculturist’s nomenclature. Madras : Government Press. https://wellcomecollection.org/works/nkuum6j9; https://archive.org/details/b28037340/page/n7/mode/2up

AINSLIE, W., 1826. Materia Indica; or. some account of those articles which are employed by the Hindoos and other eastern nations in their medicine, arts, and agriculture; comprising also formulae, with practical observations, names of diseases in various eastern languages, and a copious list of oriental books immediately connected with general science. 2 vols. London : Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown & Green (LSHTM Library *RB.23 1826); https://wellcomecollection.org/works/vu5p5mxh

ANONYMOUS 1. KIRTIKAR, Kanhoba Ranchoddas. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kanhoba_Ranchoddas_Kirtikar (Wikipedia. Viewed 19 January 2024)

ANONYMOUS 2. BASU, Baman Das. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baman_Das_Basu (Wikipedia. Viewed 19 January 2024)

GARRISON-MORTON, 2023. An interactive annotated world bibliography of printed and digital works in the history of medicine and the life sciences from circa 2000 BCE to 2022 by Fielding H. Garrison, Leslie T. Morton and Jeremy M. Norman. https://www.historyofmedicine.com/author/all/#whitelaw-ainslie

KIRTIKAR, K.R., BASU, B.D. and I.C.S., 1918. Indian medicinal plants. 2 v. text; 4 v. plates. Bahadurganj, Allahabad : Sudhindra Nath Basu, M.B., Panini Office, Bhuwaneswari Asrama : printed by Apurva Krishna Bose, at the Indian Press. (LSHTM Library *RE 1918 fol); https://wellcomecollection.org/works/v4g7fk8k; https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/bibliography/60985

MESSENGER, E., 2023. Discovering Kew’s Indian collection: past, present and future. Country-side 36 (3) : 25-27.

For more information on books on India and plants in the LSHTM Library see the LSHTM Library blog : India in the Historical Collection (pt. 2) : Plants and pharmacology https://blogs.lshtm.ac.uk/library/2024/02/06/india-in-the-historical-collection-pt-2-plants-and-pharmacology/

LSHTM Library Rare Books Collection Blogs is an occasional posting highlighting books that are landmarks in the understanding of tropical medicine and public health. The Rare Books Collection was initiated by Cyril Cuthbert Barnard (1894-1959), the first Librarian, from donations and purchases, assisted with grants from the Carnegie United Kingdom Trust. There are approximately 1600 historically important rare and antiquarian books in the Rare Books Collection.

Many of the LSHTM Library’s rare books were digitized as part of the UK Medical Heritage Library. This provides high-quality copyright-free downloads of over 200,000 books and pamphlets for the 19th and early 20th century. To help preserve the rare books, please consult the digital copy in the first instance.

If the book has not been digitized or if you need to consult the physical object, please request access on the Library’s Discover search service. Use the search function to find the book you would like to view. Click the title to view more information and then click ‘Request’. You can also email library@lshtm.ac.uk with details of the item you wish to view. A librarian will get in touch to arrange a time for you to view the item.

Researchers wishing to view the physical rare books must abide by the Guidelines for using the archives and complete and sign a registration form which signifies their agreement to abide by the archive rules. More information is available on the Visiting Archives webpage.