Here is a short history of how the School was established and what happened in our early years.

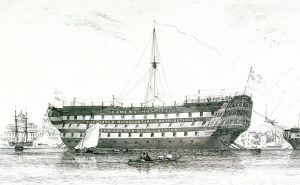

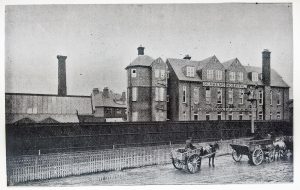

The London School of Tropical Medicine, as it was called until 1924, began as part of the Seamen’s Hospital Society and was initially located at the Albert Dock Seamen’s Hospital, in London’s East End. The Society dates back to 1821 and was borne out of the Wilberforce Committee as a charity to help people employed in the Merchant Navy or fishing fleets and their dependants. Their hospital was initially housed in quarantine ships moored on the Thames at Deptford. In 1870 the Society was granted the lease to part of the Royal Greenwich Hospital and set up onshore as the Dreadnought Seamen’s Hospital. In 1890, the Society opened another branch at the Albert Dock.

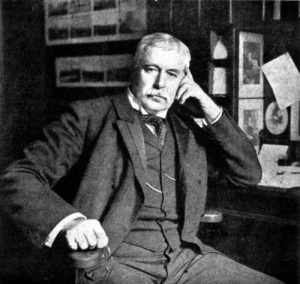

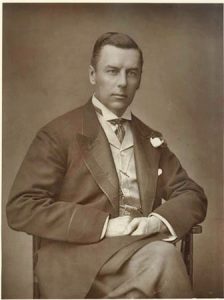

The London School of Tropical Medicine owes its origins to Sir Patrick Manson, ‘the father of tropical medicine.’ Manson trained as a doctor at Aberdeen, qualified in 1865 and received his Master of Surgery in 1866. Shortly after his training, he travelled to Formosa (Taiwan) as a medical officer to the Chinese Imperial Maritime Customs. After 5 years he transferred to Amoy where he remained for 13 years. Manson spent much of these years studying filaria and he made important discoveries relating to mosquitoes carrying filariasis and the presence of filariae in the blood stream. Having moved to Hong Kong, after six years Manson retired to Britain in 1889 and set up his own practice in London. During his time abroad as a medical officer Manson had learned about tropical diseases and was frustrated by the lack of knowledge in this field among his peers. In 1892, Manson was appointed physician at the Albert Dock Hospital and began to formulate his ideas for a national school devoted to the study of tropical diseases.

In July 1897 Manson was appointed Chief Medical Officer to the Colonial Office. Here he worked with Joseph Chamberlain was a high-profile businessman and influential politician, who was Secretary of State for the Colonial Office during the period of the School’s establishment. In December 1897, a Colonial Office memorandum was circulated to all medical schools on the need for special education and research into tropical medicine. This was followed by a fundraising circular sent to colonial governors, stressing the importance of research into malaria and the need for a school to provide specialised training for Medical Officers. In 1898 the Colonial Office invited the Seamen’s Hospital Society Committee of Management to establish a School of Tropical Medicine in connection with their hospitals.

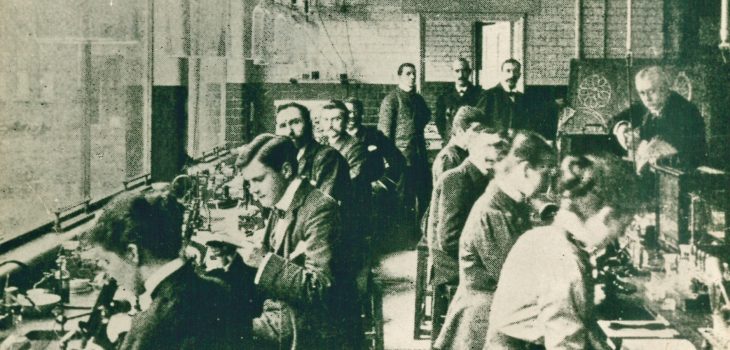

The School opened on 2nd October 1899 with 27 students enrolled. Its objective was

‘not only to acquaint the student with the diseases of the Tropics and teach him how to treat the various ailments he may meet with but also to put him in the way of investigating tropical diseases, to train him to observe, to record and to study scientifically the great tropical disease scourges’ (Report for 1899-1900)

The proximity of the School to the docks allowed for the immediate admission of patients from returning ships for treatment, and for the observation and study of tropical diseases in their acute stages.

There was one course: the Diploma in Tropical Medicine & Health (DTMH), which ran for three months, with a final exam. Sessions ran three times a year: October to December, January to April and May to July. Over the course, students were taught about the geographical distribution, clinical history, diagnosis and treatment of a large number of tropical diseases and also about hygiene in the tropics. To take the course, it was necessary to be medically qualified, although the School Committee had the power to admit other applicants under special circumstances.

During its first year, 76 students attended the School. Students, both male and female, came from all branches of the profession including Medical Officers of the British and Indian Armies, the Royal Navy, Colonial Service, Foreign Office Service, Missionary Societies, railways, trading corporations and private practitioners. On leaving the School, students worked all over the world, with a large number working in Africa, Asia and the West Indies.

Information from our student registers shows that 24 students enrolled for the 2nd session January-April 1900, including four women:

- Anne Helen Crawford, 26 from County Derry. She went on to work in Manchuria in Northern China and then in Zenana Mission House, Bombay, India

- Emily Crook, 24 from County Antrim. She went on to work at the Irish Presbyterian Mission Church in Bombay and then Manchuria in Northern China

- Maria Sharp,35, who went to work at the Lady Lyall Home, Lahore, India

- Hon. Ella Campbell Scarlett-Synge, 35 from London. Dr. Scarlett-Synge became a physician to the Emperor of Korea, worked in South Africa, Canada (where she established the Women’s Volunteer Corps) and in 1917 became a Medical Officer of Health in Northern Serbia.

In the first year of the School, there were 165 cases of tropical diseases admitted to the hospital, including malaria, dysentery, beri-beri, liver abscess, leprosy, guinea worm, filariasis, blackwater fever, plague, Malta fever and hepatitis. As part of the course, students would see cases of the diseases on the wards.

Great and important work was undertaken in the School’s early days, most notably through a number of ground-breaking discoveries and expeditions.

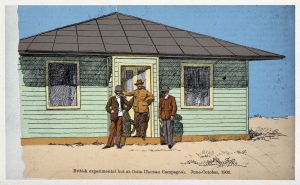

- Perhaps the most significant of these was the expedition to Italy in 1900 regarding the prevention of malaria. GC Low, Louis Sambon and AJE Terzi,

went to the Roman Campagna, near the mouth of the River Tiber, and spent three months from July to October inside a wooden hut in the malaria-infested region. By staying inside the hut from dusk until dawn they all escaped infection.

- In 1900 G.C. Low, along with Manson and Thomas Bancroft, discovered the emergence of filarial larvae from the proboscis of the mosquito intermediary.

- Dr. CW Daniels sailed to Calcutta to verify Ross’s 1897 discovery of the mosquito as the transmitter of malaria.

There were also expeditions to work on beri beri on Christmas Island; the study of blackwater fever in Central Africa, and Robert Leiper established the life-cycle of the guinea worm in Ghana.

For further information on the history of the School or to find out more about the LSHTM’s Archives, please contact: archives@lshtm.ac..uk