Within the LSHTM archives we have begun to re-examine the way we work, the stories we tell and the role we can play in promoting different versions of history. This has been inspired by the ongoing work of Lioba Hirsch, an LSHTM history research fellow working on a project entitled LSHTM and Colonialism: History and Legacy. Lioba’s research is partially based on material held within the LSHTM archives. Inevitably, the archives are steeped in the colonial history of our School. LSHTM was originally founded as an institution for the research and treatment of tropical disease, in an effort to improve the health of those working in the British colonies, which would in turn make the project of empire more profitable. As a result, the histories preserved within our collections are generally those of white, male, colonial explorers, researchers and medical professionals.

While there is certainly value in these stories, and the contributions these individuals made to tropical medicine – and science more broadly – are an important part of our School’s legacy; they are also reflective of the colonial era in which they were produced and are necessarily informed by the values and attitudes of the time. The difficulty in reconciling the celebration of scientific achievement with the true nature of its colonial legacy is something we are beginning to examine. Furthermore, the voices, experiences and contributions of the people indigenous to the countries visited by colonial researchers are often noticeably absent from the record. As a consequence we risk presenting a one-sided view of history. In the LSHTM archives we have also been asking ourselves how we can explore these hidden histories through our existing collections.

The Carpenter Diary – a handwritten journal detailing the experiences of a British scientist and his wife researching Sleeping Sickness in Uganda in the early 20th Century – has often been used as an illustration of colonial life. The diary provides a rich account of the daily lives of Geoff and Amy Carpenter as they navigated life in African environs, as well as the relative luxury of the colonial lifestyle. Inevitably, this version of 1920s’ Uganda reflects the experiences and privileges of the diarists. As a result, the journal presents a singular view of history.

For example, there is little mention of the local people the Carpenters would almost certainly have met during their time in Uganda. Indeed, their very existence goes almost entirely undocumented, beyond fleeting references that only further underline the colonial attitudes of the time. This is demonstrated within an extract from the diary from 1927 detailing a visit from the Prince of Wales. The diary refers to the ‘natives’, who had ‘turned out in numbers’ to see the Prince, being ‘very disappointed’ in his appearance. This extract is notable in that it goes so far as to acknowledge the presence of the Ugandan people. However, this is only in relation to the colonial experience and there is a sense that the disappointment referred to has been assumed rather than accurately reported.

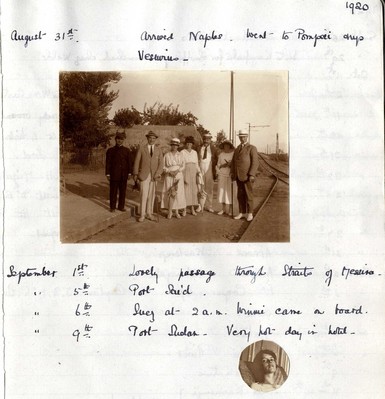

These colonial themes are similarly present in photographs included in the pages of the diary.

It’s a scene we are so familiar with, and it builds a mono-cultural picture of the past. From TV costume-dramas to film, so often this has been the typical picture of the colonies. The diary portrays the idea of the UK as the dominant culture, whichever country the coloniser arrives in. The diary entry is of ‘passing through’ Port Said, Suez, Port Sudan. There is the absence of anything other than the familiar group: maybe a servant in local costume to one side, to give literally, local colour.

This type of photo instantly portrays a certain strand of white colonial society, and it is one that often features in archive displays. Often, these photographs of middle-class colonial employees are the images deposited with an archive (these are people who had cameras and wanted to record their leisure activities) and so we build an unrepresentative picture of the past that becomes embedded in our culture. We are re-engaging with these images in light of decolonisation and want to collect more diversely in future.

By re-evaluating material such as the Carpenter Diary we can expose its limitations. However, while drawing attention to the gaps within our collections is an important part of the decolonisation process, it does not resolve the issue of how to represent these missing histories. This is not the first time LSHTM archives have explored this problem. In 2015 we collaborated with actors and script writers on Archives Alive, a project which sought to bring to life the, often overlooked, contributions made by women to the advancement of global health. A blog post about the project can be found here. Elsewhere, historians such as Saidiya Hartman have responded to absences within the archive by using techniques borrowed from fiction writing in order to tell otherwise forgotten stories. We hope to take inspiration from this kind of research; to shed light on the stories of colonised people by similarly using the available archival material in new, creative ways. Through this work we are attempting to critically engage with decolonisation as a practice within the LSHTM archives – this blog represents a first step along this path.