Yellow fever, a viral disease transmitted by infected mosquitoes, was “one of the most dangerous infectious diseases of the 18th and 19th centuries, resulting in mass casualties in Africa and the Americas,” according to one recent article. For years up to the nineteenth century, debate raged over how the disease was transmitted. These books from the Library’s Historical Collection offer a glimpse of the different theories that were circulating by the end of the nineteenth century.

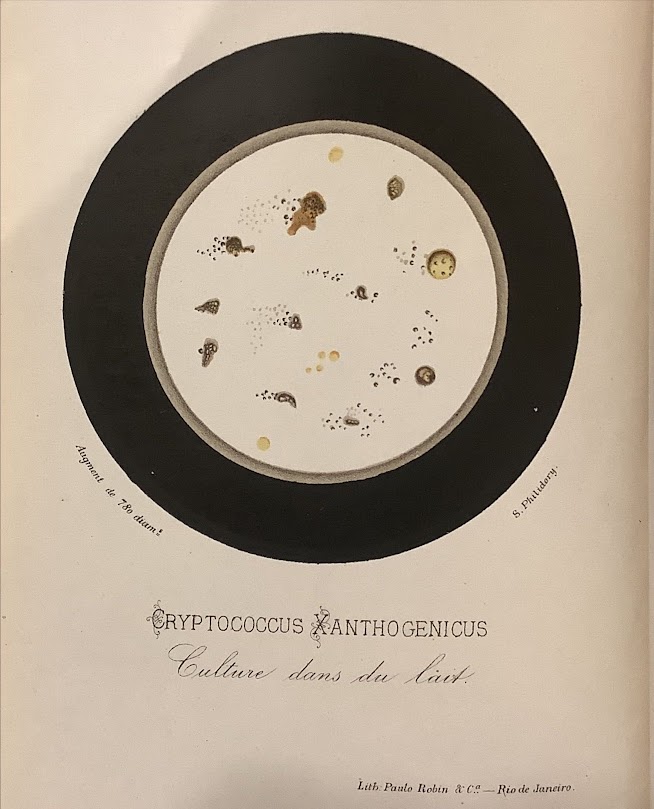

Yellow Fever as a Fungus

Domingos Freire, the author of this book, claimed to have isolated the microorganism responsible for yellow fever. However, the Cryptococcus fungus is now known to be distinct from the yellow fever virus. Though it does not cause yellow fever, it can cause a different disease when it infects immunodeficient people.

Yellow Fever as a Non-Pathogen

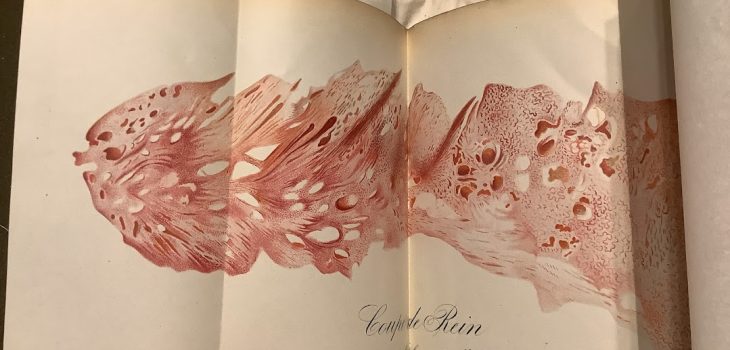

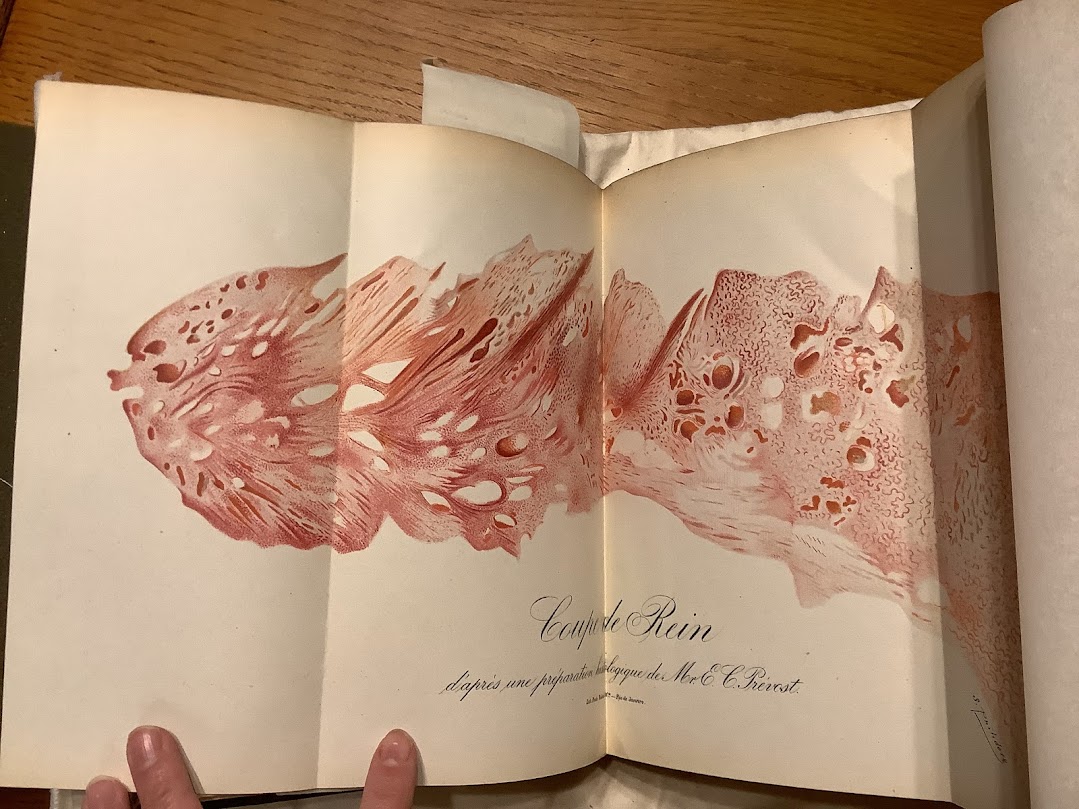

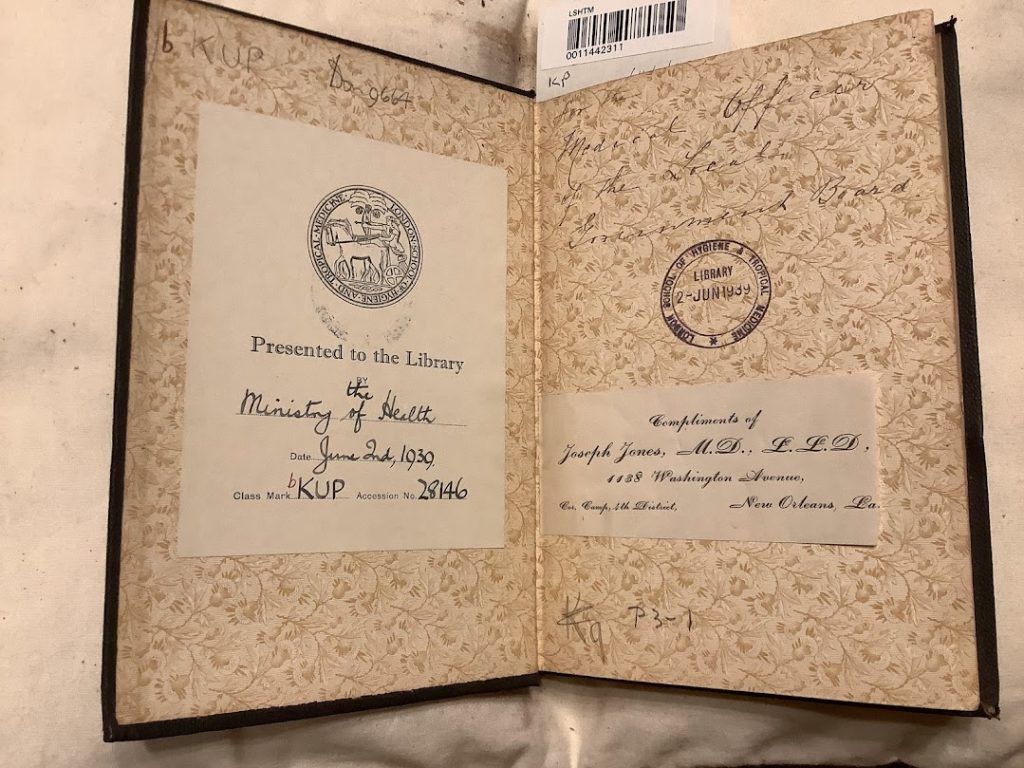

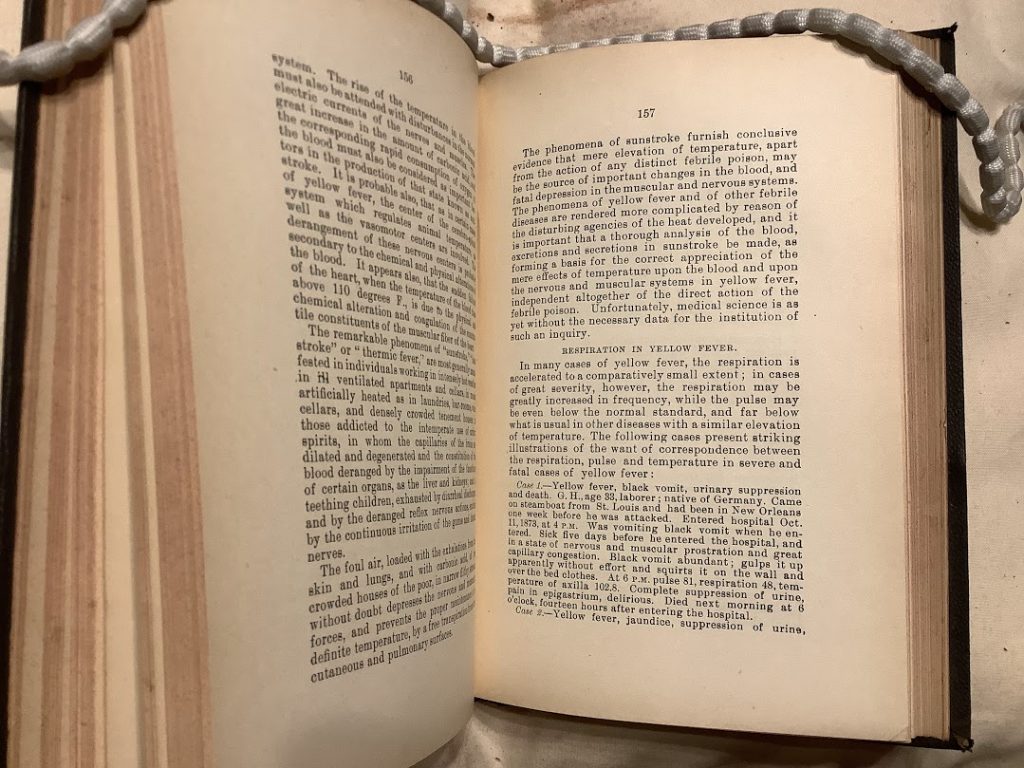

This book was once owned by the Ministry of Health and was presented to LSHTM Library in 1939. The author, Joseph Jones, argues that “the poison of yellow fever is a living germ of animal or vegetable nature or origin” (p. 30). However, Jones declines to expand much further than that, preferring to focus on case histories and the disease’s effects on different bodily organs and systems.

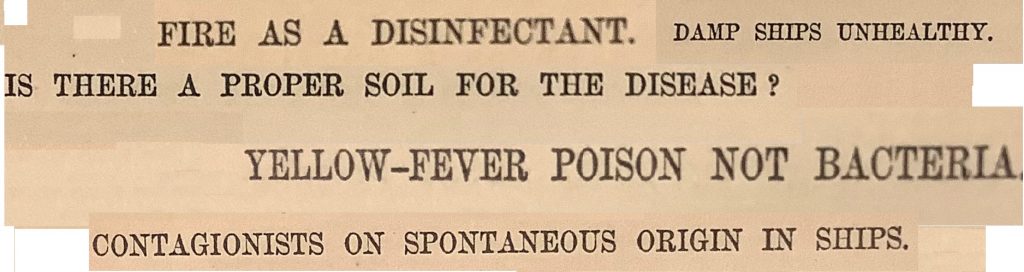

This collage of titles from Yellow Fever: A Nautical Disease shows the author John Gamgee’s argument in action. Yellow fever is now known to be transmitted by infected mosquitoes, which ventilation would only somewhat have helped with. Gamgee’s thesis is that yellow fever can be prevented by cleaning merchant ships thoroughly. It says it is a condition which emerges spontaneously in people when they are on ships. It is not contagious like smallpox, as there is no “secretion” transmitting the disease. Instead, he thinks it comes from a “poison” that emerges under certain conditions (p.16).

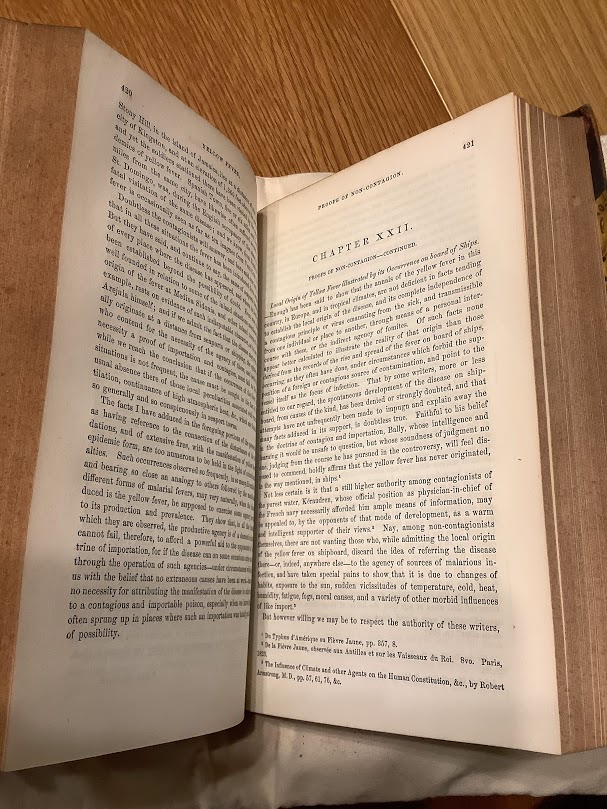

This book offers a similar argument for yellow fever’s arising not from a pathogen, but in the body in response to certain poor conditions. It notes several cases where, the author La Roche claims, yellow fever arose from rotting flesh in the vicinity. One might wonder if that was what attracted the infected mosquitoes. As observed by Gianchecchi et al (2022), the “highly populated cities” of the US of the nineteenth century “constituted a favorable condition for the spread of YF virus imported by ships from the Caribbean, with repeated epidemics in the US occurring in cities such as New York City, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and New Orleans.” Therefore the attention this book and others paid to damp and unsanitary conditions and to ships in general was not entirely off-base. Nonetheless, commentators had missed the fact that both might be ideal conditions for mosquitoes.

Yellow Fever as a Bacterium

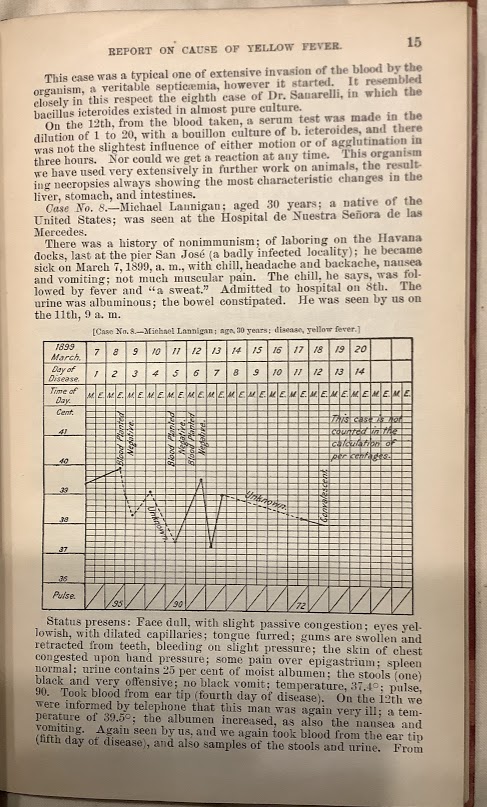

This report argues that the “Sanarelli bacterium” Bacillus icteroides (later revealed to be a secondary infection) is responsible for yellow fever. This report says it verified Sanarelli’s claim to have linked the bacterium with yellow fever and adds that it has successfully determined that the infection came through the respiratory tract (p.8). The investigation took place in Havana, Cuba, during the preceding year. Pictured (p. 15) is part of a series of case histories from Havana identified as yellow fever patients.

Published in 1898, this book summarises the debate at the time, including the Sanarelli bacterium but also observes its aptness to occur near coal ships, ships with dirty bilges, or ships ballasted with damp goods like mud or green wood (p.13).

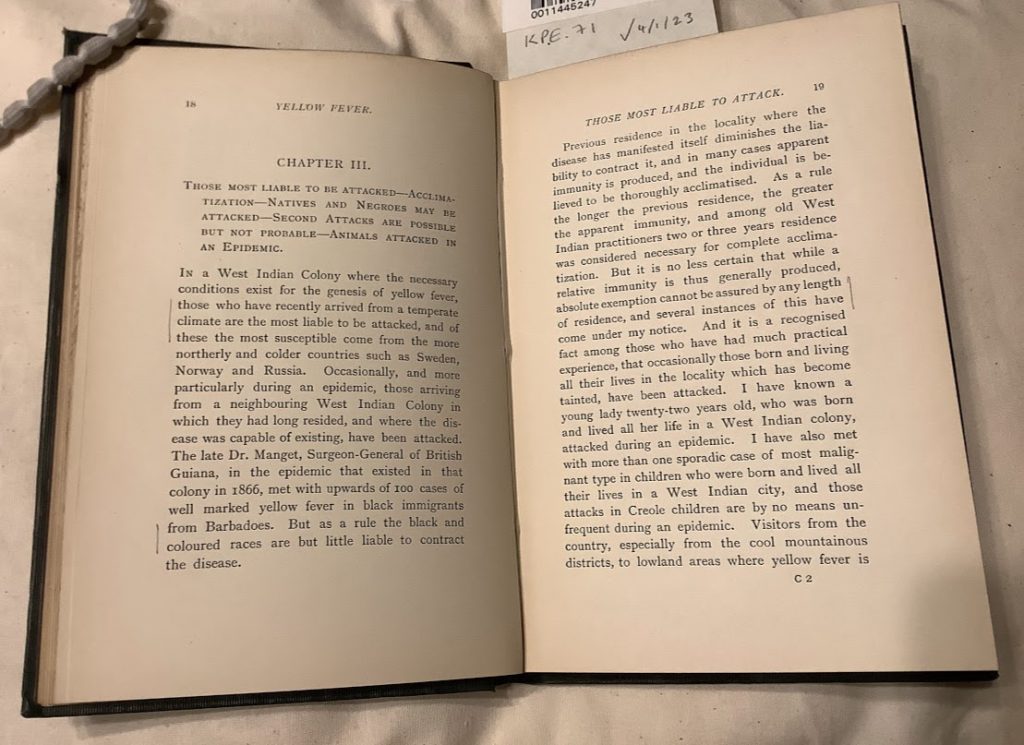

This is one of the books that makes it clearest what benefits the colonial project envisioned from finding the cause of yellow fever. In the opening pages, Anderson describes the “frightful mortality” among “European troops” stationed in the West Indies over the nineteenth century. He goes on to argue that this was due to poor sanitary conditions and inappropriate kit, but that much of this had been addressed. Later on, in Chapter 3 (pictured) he claims that immigrants to the West Indies, especially white ones from northern Europe, were the most susceptible to yellow fever. However, based on what we now know of the virus, this was most likely due to survivors of a bout having acquired immunity to it.

These books came at a time just before popular acceptance that it was a virus that caused yellow fever. This theory was popularised by US Army doctors in 1901, particularly Walter Reed. They confirmed the hypothesis put forward by Carlos Finlay, a Cuban doctor, twenty years before. The virus itself was isolated, the first virus to be so, in 1927 (Staples and Monath 2008), and a vaccine was produced not long after (Frierson 2010).

Library users are welcome to consult any of these books on Library premises. To reserve a book for consultation, just go to their catalogue entry on Discover while you are logged into your LSHTM account and follow the instructions underneath the heading “Get It.” You’ll receive an email when it’s available. However, please note that these books will need to be read within the Library and cannot be borrowed like most other resources.

Sources and further reading

Douam, Florian, and Alexander Ploss. “Yellow Fever Virus: Knowledge Gaps Impeding the Fight Against an Old Foe.” Trends in microbiology (Regular ed.) 26.11 (2018): 913–928.

Frierson, J. G. “The yellow fever vaccine: a history.” Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine. 2010 Jun; 83(2):77-85. PMID: 20589188; PMCID: PMC2892770.

Gianchecchi E, Cianchi V, Torelli A, and Montomoli E. Yellow Fever: Origin, Epidemiology, Preventive Strategies and Future Prospects. Vaccines (Basel). 2022 Feb 27;10(3):372. doi: 10.3390/vaccines10030372. PMID: 35335004; PMCID: PMC8955180.

McNeill, J. R. “Yellow Jack and Geopolitics: Environment, Epidemics, and the Struggles for Empire in the American Tropics, 1650–1825,” OAH Magazine of History, Volume 18, Issue 3, April 2004, Pages 9–13, https://doi.org/10.1093/maghis/18.3.9

Staples, J.E., and T.P. Monath. “Yellow Fever: 100 Years of Discovery,” JAMA. 2008; 300(8):960–962. doi:10.1001/jama.300.8.960

https://www.rmg.co.uk/stories/blog/library-archive/sickness-health-sea

https://asm.org/Articles/2021/May/History-of-Yellow-Fever-in-the-U-S