By Joseph J. Valadez, Ulrike Seeberger (Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine)

HIV/AIDS is one of the first global epidemics that killed complete generations of young adults. Its transition towards a chronic condition is one of the great achievements of medicine, pharmacy and public health. However, as a chronic disease, it remains a huge challenge to the health sector in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) as its requirements differ massively from the management of acute conditions. Instead of treating patients according to cardinal symptoms and stopping treatment after recovery, HIV requires permanent, lifelong treatment even though the patient may not experience any symptoms. Furthermore, the management depends upon regular clinical and immunological monitoring to rule out side effects of the medication and drug failure. All concerns have to be fulfilled on a long-term basis to ensure good patient outcomes with low morbidity and mortality. HIV/AIDS remains a major challenge for health sectors that are more used to treating acute conditions (for example, Malaria, Pneumonia, Diarrhoea). However, its management may become an example for an approach that could apply to other emerging chronic conditions like diabetes, high blood pressure and chronic heart failure with similar requirements to the health sector.

Scale up of HIV/AIDS services in Uganda

Uganda, like many LMICs, has scaled up their services for people living with HIV/AIDS during the last two decades. In this context of rapid scaling up of services and changing requirements concerning management, quality of care has gained more and more attention as it is paramount for reducing morbidity and mortality of HIV/AIDS. However, most studies and surveillance systems are concentrating on the availability of a service rather than on its quality.

Our study published in Health Policy and Planning could be a starting point to close this information gap. We examined the on-site quality of care for patients on antiretroviral treatment in northern Uganda. The overall quality of care was low; standard first-line antiretrovirals were available and dispensed and patients stated they took them regularly. However, clinical and immunological monitoring for drug resistance, side effects or opportunistic infections did not take place. Neither did the adaptation of medication in case of treatment failure.

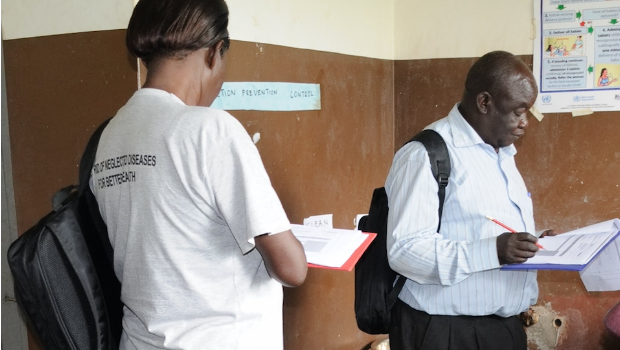

We used an approach and a method that could easily be replicated on a nationwide level or elsewhere. The lot quality assurance sampling technique measures coverage with health services in a geographical area, comparison of different areas, and an on-site examination of clinical care and support services in a facility. Consequently, it enables health system managers to identify areas (geographical and technical) that need attention and support, and policymakers to determine whether a chronic health system problem exists or whether a problem is health facility or health service specific.

Conclusion

Whether northern Uganda is an area that needs extra attention to improve care or whether this problem is a more widespread one, should be investigated. We hoped that we could find greater variation in the results and identify areas of care that need improvement and those that do not. However, nearly all areas failed. To find out about the consequences for the patients, requires further studies such as immunological monitoring.

We are aware, that the measurement highly depends on the indicators we choose and questions we ask. In our study, we used the national antiretroviral treatment guidelines as basis for the choice of indicators.

However, we are curious to discuss different experiences others have had when assessing the quality of care in LMICs and would like to see more patient outcome studies to verify or call into question our approach.

Image credit: Joseph J. Valadez