By Neha Purohit (Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, India) Rakesh Gupta (Ministry of Women and Child Development, Government of India), Girdhari Lal Singhal (Office of Chief Minister, Government of Haryana) and Shankar Prinja (Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, India)

Background

An alarming number of 13.5 million girls have gone missing since the last three decades from 1987-2016 in India. It is more disturbing to note that number of missing female births increased from 3.5 million (1987-1996) to 5.5 million between 2007-2016. The issue is not hard to demystify, and we believe that all individuals, irrespective of their gender, relate to it. Deviation in the natural sex ratio at birth (SRB) and reproductive predominance of the male sex are the reflections of patriarchal social norms, particularly patrilineality (inheritance through male descendants), patrilocality (tradition of relocation of married female to husband’s house), and prevalent dowry practices where bride’s family must bestow gifts of substantial monetary value to the groom’s family for marriage.

These age-old cultural traditions which link sons to social and financial security, disincentivize families to even wish for daughters. The access to sex selective medical technologies and fertility decline have exacerbated the issue and shaped intentions of female . India has regulatory acts in place since the last few decades which penalize families as well as healthcare providers involved in sex determination before and after conception and illegal abortions based on sex. However, they were not able to improve the dwindling SRB.

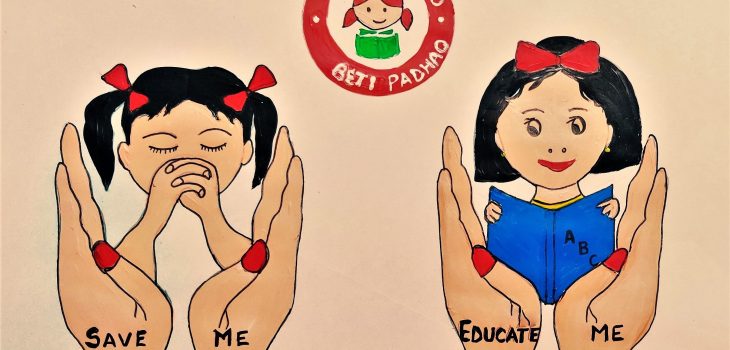

“Beti Bachao Beti Padhao” (B3P) or “Save and Educate Daughters” programme

The B3P programme was launched in 2015 by the government of India to address the issue of rampant female foeticide and declining SRB through sustained social mobilization campaigns favouring the acceptability of daughters, strict implementation of legal frameworks and various schemes to promote educational and economic status of females. A shift in approach from sole focus on regulatory measures and fragmented social interventions to integration of regulatory, social, and female empowerment policies was adopted by the government.

Among the Indian states, the well-developed state of Haryana (in terms of per capita income) had consistently been one of the most gender critical states and recorded SRB below 900 (less than 900 girls per 1000 boys) from 2005 to 2015. B3P was hence implemented in a mission mode across the state through intensive and integrated multi-stakeholder action. An evaluation of B3P programme conducted after one year of its implementation in Haryana, informed about its significant positive impact on SRB and this rapid change was majorly attributed to strict implementation of regulatory interventions.

Existing evidence suggests that the programmes which rely heavily on regulatory and enforcement measures only have a short-term impact owing to problems in sustaining strict programme implementation. It is related to the fact that both the service supplier and the consumer work in agreement to defeat the intervention for financial and social incentives. Furthermore, reproductive tourism, and advancement in sex determination technologies pose a threat to these interventions.

Medium term evaluation of B3P programme

We undertook an investigation into medium-term impact of B3P programme through an interrupted times series analysis of civil registration data from 2005 to 2019 to distinguish whether B3P interventions induced a significant effect on SRB than the conventional pattern observed during the pre-intervention timeframe. It was overwhelming to note consistent improvement in SRB throughout the implementation of the programme. The positive findings coming from a state where the birth of boys is celebrated with pomp and show, in contrast with the birth of girls, which is ridiculed and cursed, made it more special. However, the success was not uniform across the districts.

To be sure the success could be attributed to B3P, we examined the other interventions during the period which could have affected SRB and concluded that B3P has been an overdue intervention to ensure survival of girls. The results instilled optimism that the deep-rooted issue of the gender gap in India can be reversed through sustained implementation of the B3P programme. The strict implementation of regulatory measures has been instrumental in tackling the skewed SRB in the early phase. But the way-to-go strategy for the medium-term accomplishment was the proactive implementation of innovative initiatives to raise consciousness of the community against the menace and to promote girls through regular rallies, orientation programmes, birth celebration of girls, folk performances, film shows, etc. The third set of initiatives under the programme which aimed to create an enabling environment for health and education of girls and overall female empowerment is likely to sustain the change in the long-term. Nonetheless the credit also goes to proactive leadership, good governance, strong interdepartmental coordination, and strict execution of the integrated interventions, since a programme is as good as its implementation. The findings can be important to other Indian states and South Asian countries, struggling with the grave issue of missing females due to the deeply entrenched gender norms.

Conclusion

The effectiveness of regulatory measures will constantly depend on the quality of monitoring systems and legal frameworks to penalize the offenders. The long-term success of the programme will rely on continuity of efforts to bring about social change by sensitizing citizens towards the existing age-old inequalities and by challenging the patriarchal norms of the society to create a more favourable environment for girls through policy reforms. Effective implementation relies on effective evaluations. Hence, periodic evaluations of the programme will be essential to delineate the enabling and hindering factors for the closure of the gender equity gap and creation of egalitarian welfare societies where a child will just be a “child”, not a boy or a girl.

Image credit: Rita Sharma