Authors: Diksha Singh1, Pankaj Bahuguna1, Lorna Guinness2, Shankar Prinja1

1Department of Community Medicine and School of Public Health, Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, India

2 International Decision Support Initiative (IDSi), Centre for Global Development, London, UK

In 2018 India launched AB PM-JAY as part of the plan to achieve the vision of Universal Health Coverage. AB PM-JAY includes a plan to roll out comprehensive primary health care alongside the introduction of a vast insurance programme for the vulnerable. But while there was and is much fanfare around the insurance programme, much less attention seemed to be focussed on the primary care roll out. Over 150,000 existing sub-health centres and primary health care centres are being upgraded from largely maternal and child health care provision to Health and Wellness Centres with a broader scope, that includes diagnosis and management of non-communicable diseases, as well as improved infrastructure and staffing. Notable in staffing is the inclusion of a new cadre of mid-level health care provider. As health economists we noted there was a distinct lack of discussion around the financial and economic implications of this transformation. We were inspired to try and fill this gap. We wanted to understand the financial implications of such a transformation, and to suggest per capita rates at which providers could be reimbursed for providing primary health care services. As previous HPP publications have documented, the process underlined several important factors that need to be considered when trying to make projections of cost or to understand the costs of scaled up programmes. We summarise the key issues we think need to be addressed when costing health service scale up and outline them here:

1. To consider the quality of existing service delivery

Prior to the reforms, quality of primary care in India was variable, with many facilities under-resourced by pre-existing standards. In our model, we costed the improvement of service delivery to achieve pre-existing norms, before estimating the additional cost of the Health and Wellness Centres. If the cost of scale-up is built on the existing cost structures of poor quality service provision, it is likely to grossly underestimate the need for actual spending. As recent evidence points out, a higher proportion of amenable mortality globally can be attributed to poor quality care, than unmet need.

2. To account for infrastructure gaps, human resources and consumables separately

Scaling up has different implications for different types of resources. The spend on new infrastructure will only happen once. Increased human resources will require a sustained rise in the recurrent spend. The increase in the cost of consumables might be driven by a combination of the broader range of services as well as changes in demand resulting from upgraded facilities. Each component of the cost function therefore needs to be treated separately and according to the respective cost drivers.

3. To Incorporate geographical heterogeneity in current service provision

Not all facilities are the same. Rural and urban facilities will cater to different population densities and different disease profiles. Some Indian states are generally better resourced than others. These variations had to be factored into our costing model to avoid large errors in the estimates.

4. Robust cost data

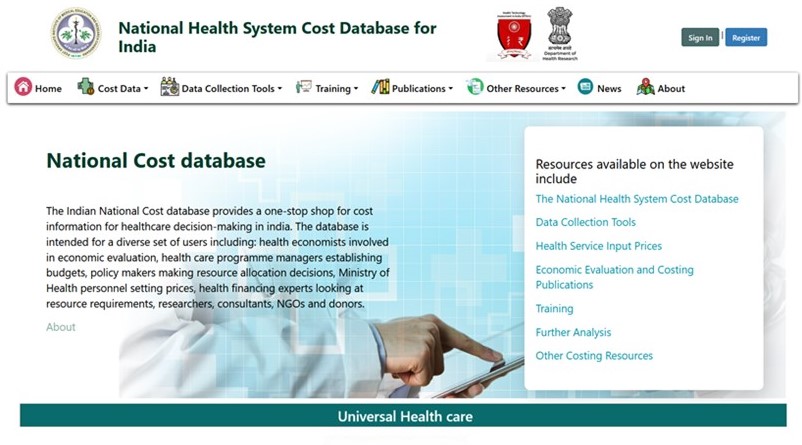

Just as with epidemiological models, cost estimates are only as good as the input data. We were able to draw on a robust set of cost data from the growing Indian National Health System Cost Database. These data were collected from over 150 facilities across 6 states using a standardised methodology and are available broken down by line item and activity. This allowed us to incorporate quality and geographical variations as well as to cost individual line items appropriately. Country level health service cost estimates are critical to informing policy – we’d like to encourage the further development of these types elsewhere in low- and middle-income countries.

5. To address policy needs

Instead of providing a single figure for the overall cost of full coverage, which can be discouraging given the fiscal space constraints, assessments should show the incremental investments for small increases in service and population coverage over different time periods. In addition, the costing results should distinguish between one off and future spending implications. It should show alternative strategies for scaling-up by region and over different timeframes to help governments develop the most feasible scale up path.

Conclusion

Given the push for universal coverage, countries are in the process of preparing strategic plans to cover essential services. However, we found that discussion around the financial implications, at least in India, was limited. Our model helps highlight the importance of adequate discussion of the costs of universal coverage, and provides a basis on which to argue for increased budgetary allocations. Improving the data and the data systems that feeds these models is an ongoing challenge. We would like to see continued monitoring of the costs of Health and Wellness Centres and for this to feed into the National Health System Cost Database to inform future budget projections as well as economic evaluation. We believe that such assessments of fiscal implications of future plans are fundamental in ensuring the necessary resources required to achieve realistic targets.