By Lydia Davidson (London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine)

Note: This post was written prior to the Myanmar Military Coup in February, the situation is now very different. The coup serves to highlight the challenges faced in Myanmar. I would like to pay my respects to my nursing colleagues in Myanmar who continue to strive for improvement despite these challenges.

The healthcare system in Myanmar has faced significant challenges, despite continuous efforts at improvement, since the establishment of the new government in 2010. The lack of human resources has often been the focus of discussion. While there is no doubt that the quantity of nurses in Myanmar is problematic (9.99 nurses and midwives per 100 000 population), the system of frequent nurse rotation limits the quality of nursing care the existing nurses are able to give. The rotation is difficult to change due to system centralisation and little room for upstream feedback. The leadership of the nursing profession may be a key factor in navigating past these barriers.

Rotation

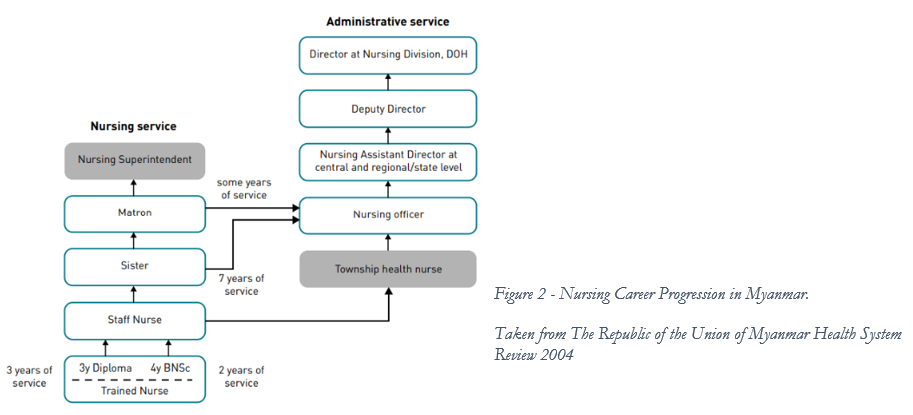

The nurses who deliver clinical care (these are identified as Trained Nurses who are newly qualified with up to 3 years of experience and Staff Nurses who have 3 years or more of experience) are rotated between wards every 4 to 9 months. A nurse does not stay in one ward for a longer period until they become a Sister, which is largely a management and administrative role. The rotation of nurses in Myanmar does not follow a particular pattern and nurses may move from an adult surgical ward to a neonatal ward, which limits their development of specialist skills. Without these skills it is not possible to improve quality of care – research from the U.S. places skilled nurses as a safety mechanism in protecting patients from error and as central in achieving good healthcare outcomes.

Centralisation and Responsiveness

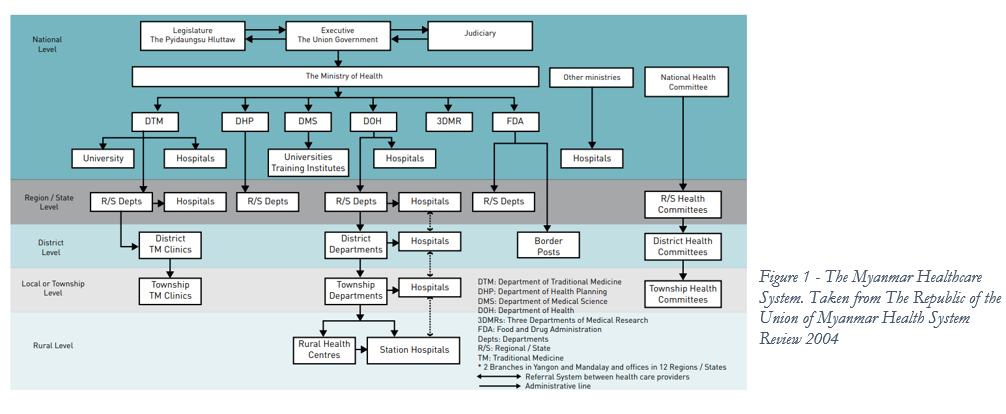

The structure of the healthcare system (fig.1) is hierarchical and centralized. The Ministry of Health (MOH) is responsible for setting rules and standards, while the Regional/State, District and Township Departments are responsible for monitoring and enforcing of those standards. The pathway for raising concerns from Township hospital up to the Ministry is via all departments between the two and only MOH is empowered to make decisions. This makes responsive upstream feedback challenging and is a barrier to initiating policy change. References have been made to hospitals being built but not being able to function effectively as the incorrect number of staff were recruited by the MOH. The impacts of centralization are felt throughout Myanmar. A recent study on health system strengthening in the conflict affected border regions of Myanmar places importance on decentralization as a way to improve quality and efficiency of local health systems.

This illustrates that the hierarchy and centralization create an asymmetry of information, that makes governance difficult and service delivery even more so.

The connection of rotation and a hierarchical health care system is reflected in the career progression of nurses. (Fig 2). If nurses would like to progress above the level of Staff Nurse then the years of rotation must be completed. As the roles of Sister and above largely become administrative, this separates years of nursing experience and the acquired clinical skills from patient care – those nurses with more experience are not becoming clinical leaders but instead moving into administration. It is the system itself that is driving nurses to rotate, which in turn impacts on nursing skills, and is then compounded by limited upstream feedback and a rigid career structure.

Nursing Leadership

The leadership of nursing in Myanmar may be able to navigate around these. At present challenges remain, for example, there is very little information about the nursing profession in Myanmar – there is currently no central registration system. Additionally the Myanmar Medical Association (MMA) have formed links with professional bodies in the UK to provide opportunities to the medics in Myanmar, without any similar program being clear for nurses from the Myanmar Nursing and Midwifery Council (MNMC).

There are early indications of support being established for the nursing profession. A growing number of degree level courses are open to nursing, and Nursing Universities have been established with specialist nursing courses available. The MNMC was reconstituted in 2018, indicating that internal processes are under reflection and review.

The MNMC is well placed to advocate the changes necessary for improving the quality of nursing and to create the structures which could overcome the barriers to modifying the rotation system. Suggested steps are:

- Take the lead on creating a central register of nurses. Communicate with the nurses in the hospitals to listen to nurses’ experience and understand problems within service delivery.

- Create a place for these professional discussions to be had. The Myanmar Paediatric Society hold an annual conference, perhaps the MNMC could take a similar approach. This could be done in association with international bodies and the higher education institutions within Myanmar to create learning opportunities and strengthen nursing leadership in Myanmar.

This would place the MNMC and the Nursing Universities as advocates for nursing to the MOH. The rigidity of the system has been presented as a barrier – but if change is authorized from the MOH then implementation is often fast, and so if the proposed changes have a solid foundation then this speed and uniformity can be seen as a benefit. Financing of healthcare in Myanmar is increasing, but still under constraint. It should be emphasised that reducing the rotation of nurses does not imply recruiting more staff (although as stated initially, this recommendation runs alongside increasing the workforce, rather than instead of increasing the workforce), so the immediate financial implications ought to be minimal. Discussing lengthening rotation must be undertaken between all actors as changes in some hospitals but not others would lead to an imbalance in nursing distribution.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the system of rotation is a major factor in limiting the quality of care given by nursing staff in Myanmar. But there are structures within the healthcare system that act as barriers to change: a hierarchical and vertical healthcare system which leads to a lack of and an asymmetry of information about nursing in Myanmar, the consequence of which is poor governance. Improving nursing leadership and enabling the MNMC and the education institutions to act as advocates may provide ways to overcome these barriers.