By Jamie Enoch (Research Assistant in AIDS Policy, LSHTM)

Has 2016 been one of the worst years in history? Whatever your take on the overall state of the world, there is room to approach World AIDS Day with cautious optimism. UNAIDS estimates that over 18 million people are accessing antiretroviral treatment for HIV, and 77% of pregnant women with HIV are on treatment to prevent transmission to their babies. In research, there have been exciting steps forward towards an HIV vaccine, antibodies that can neutralise HIV and injections or contraceptive-style implants which could prove a more discreet option for taking pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). But the future of the AIDS response hangs precariously in the balance; if there are 18.2 million people on antiretrovirals, then there are at least another 18.5 million people living with HIV without access to treatment.

Stigmatization

In the UK, Wo rld AIDS Day is focussing on both the progress that’s been made since the 1980s, and the continuing need to tackle stigma and myths around the disease which stubbornly persist. We’ve seen Prince Harry take an HIV test live on TV which is thought to have boosted HIV testing, perhaps the UK equivalent of the Charlie Sheen effect on HIV awareness in the US. However, debates (settled uneasily, for now) raged around whether the NHS or local authorities should fund PrEP, with headlines occasionally striking a distinctly 1980s tone, and this in the UK where we like to think tolerance is relatively high and discrimination relatively low.

rld AIDS Day is focussing on both the progress that’s been made since the 1980s, and the continuing need to tackle stigma and myths around the disease which stubbornly persist. We’ve seen Prince Harry take an HIV test live on TV which is thought to have boosted HIV testing, perhaps the UK equivalent of the Charlie Sheen effect on HIV awareness in the US. However, debates (settled uneasily, for now) raged around whether the NHS or local authorities should fund PrEP, with headlines occasionally striking a distinctly 1980s tone, and this in the UK where we like to think tolerance is relatively high and discrimination relatively low.

In many contexts, the outlook for HIV prevention and reducing stigma is bleak and the “post-truth” paradigm seems to apply as much to AIDS policy as other spheres. In contrast to what decades of trials, epidemiology and social science research tell us could help to curb the HIV epidemic, the AIDS response in many countries remains deeply ideological. The Philippines has cut funding for contraception. Russia continues to ban opioid substitution therapy which could reduce HIV transmission among injecting drug users, and “prefers to blame and criminalise drug users” for the rocketing incidence rates. And 2017 will usher in a Vice President-Elect of the United States who in 2000 made sinister claims about channelling HIV funding away from organisations which “celebrate behaviours that facilitate the spreading of the HIV virus” to instead fund gay conversion therapy.

One challenge from a research point of view is unpacking how such stigmatising, dehumanising attitudes and policies affect HIV prevention, testing and treatment. Excitingly, a nested study in the PopART trial is aiming to do just that, exploring the effects of stigma on the uptake of universal (i.e. community-wide) testing and treating for HIV. This will hopefully provide new insights into the extent to which prevention and treatment at the population level may reduce stigma. And it could also shine a light on a deeper issue in clinical HIV research, namely how far HIV-related stigma may undermine the real-world impact of interventions which have proven effective in controlled trial settings.

HIV among adolescent women

One urgent issue for this World AIDS Day is the alarming burden of HIV among adolescent women, the emphasis of UNAIDS’ Get on the Fast Track report. Girls and young women, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, face a range of social and structural vulnerabilities, such as poverty, lack of schooling and marginalisation, which put them at greater risk of violence, exploitation and HIV infection. For example, as shown in an HPP study which sought to systematically quantify girls’ vulnerability, vulnerable girls in Botswana and Mozambique were less likely to insist on sex with a condom, thus increasing risk of HIV transmission.

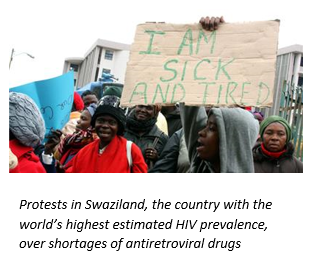

Once tested, young women are also more likely to face considerable barriers in accessing and adhering to antiretroviral treatment. An ethnographic study in HPP of married women in Swaziland provides a powerful anthropological counterpoint to the epidemiological concept of being “lost to follow up” and the programmatic notion of a “treatment cascade”. Nkunku, a young Swazi woman, is described weighing up the pros and cons of accessing treatment for herself and her unborn baby while fearing the potentially ruinous consequences of disclosing HIV-positive status to her husband, and her and his families. Her linkage to treatment is fraught with obstacles imposed by rigid gender norms, patriarchy and delicate family dynamics. Nkunku, her husband and first child fortunately all enrolled on antiretrovirals by the end of the study period. However, another woman involved in the study, Sibongile, died because the lengthy process of negotiating permission and money from her husband meant she could not travel to the three adherence-counselling sessions that were a prerequisite to starting treatment.

Once tested, young women are also more likely to face considerable barriers in accessing and adhering to antiretroviral treatment. An ethnographic study in HPP of married women in Swaziland provides a powerful anthropological counterpoint to the epidemiological concept of being “lost to follow up” and the programmatic notion of a “treatment cascade”. Nkunku, a young Swazi woman, is described weighing up the pros and cons of accessing treatment for herself and her unborn baby while fearing the potentially ruinous consequences of disclosing HIV-positive status to her husband, and her and his families. Her linkage to treatment is fraught with obstacles imposed by rigid gender norms, patriarchy and delicate family dynamics. Nkunku, her husband and first child fortunately all enrolled on antiretrovirals by the end of the study period. However, another woman involved in the study, Sibongile, died because the lengthy process of negotiating permission and money from her husband meant she could not travel to the three adherence-counselling sessions that were a prerequisite to starting treatment.

The article therefore makes a powerful case that HIV programmes need to build in more flexibility, responding sensitively to the profound psychosocial complexities surrounding HIV at the household level experienced by women and girls. However this could prove challenging as funding for the AIDS response slows and uncertainty prevails around the US’ role in global HIV financing (of which it currently provides two-thirds). And as donors transform or transition their programmes and priorities in the face of scarce resources there will always be a human cost to consider. This is vividly illustrated in a cautionary tale from Lesotho, where donors abruptly reduced funding in 2012 for HIV lay counsellors who play a key role in uptake of antiretrovirals in rural areas. The number of counsellors dropped from 487 in 2011 to 165 in 2012, and in the same period antiretroviral coverage dropped by 10%. While there may not be a precise cause/effect relationship, the study makes a persuasive case for ensuring transitions in HIV funding and programming are effectively managed. As funding dries up, the kind of cost-effectiveness modelling deployed in another HPP study – on lifelong antiretroviral therapy to prevent mother to child HIV transmission – will be ever more crucial in shaping funding decisions to local political and economic realities.

Tools

World AIDS Day is an important opportunity to commemorate the hard-won successes of people affected by HIV, advocates, activists, civil society and scientists across the world. There are more tools at our disposal to reach the hard-to-reach (for example HIV self-testing), the Global Fund has thankfully been replenished and our body of knowledge about HIV/AIDS is growing all the time. It may sound trite, but behind every statistic about more antiretroviral enrolment or prevention of HIV transmission from mother to child are individuals with renewed hope for themselves and their families. This really struck home at a STOPAIDS event for World AIDS Day, where Sanelisiwe, a Mothers2Mothers Peer Mentor from South Africa, moved and inspired the audience with the story of her – ultimately successful – journey towards ensuring that her child was born HIV-negative.

Final note

Nevertheless, all are agreed that there is no room for complacency if we are going to achieve the global “90-90-90” targets. UNAIDS has ‘sounded the alarm’ about new HIV infections. Only 60% of people know their HIV status. Key populations with high HIV risk like people who inject drugs and LGBT people remain marginalised and subject to punitive laws. And there is now widespread concern among the broader health community about the deteriorating geopolitical climate. But at the micro-level of the AIDS response, among brave, proactive individuals, families and communities, there is a huge amount to celebrate this World AIDS Day. As the author Rebecca Solnit reminds us in Hope in the Dark, “The grounds for hope are in the shadows, in the people who are inventing the world while no one looks”. HIV/AIDS as a public health threat certainly isn’t over, but momentum, solidarity and creative energy is still very much alive and must continue to be harnessed in the global response to the pandemic.

Oxford University Press are highlighting World AIDS Day with recently published relevant articles and a quote from our Director Peter Piot: http://blog.oup.com/2016/12/fighting-stigma-hiv-aids/

Related Health Policy and Planning articles: http://bit.ly/2gVsJXH

Image credits: Jimma University Specialised Teaching Hospital, Ethiopia, courtesy of Wellcome Images, Al Jazeera, MTV Shuga