By Michael R. Snyder (Johns Hopkins University)

With the five-year anniversary of the West Africa Ebola outbreak declaration approaching, now is an appropriate time to reflect on progress made in improving global public health preparedness. Has the international community learned the lessons of the 2014-16 Ebola epidemic? What have multilateral organizations, like the World Health Organization and the World Bank, done to prevent another catastrophic pandemic from occurring? Have the measures enacted by the global community in the wake of the Ebola epidemic resulted in sustainable advances in public health preparedness and response to infectious disease events?

These were among the key research questions that guided our study, “Review of international efforts to strengthen the global outbreak response system since the 2014–16 West Africa Ebola Epidemic,” published online in Health Policy and Planning.

Following the Ebola outbreak in West Africa, many in the international community were committed to preventing another catastrophic outbreak from potentially killing thousands of people and threatening global stability. To assess progress made in shoring up the global emergency response system, my co-authors and I undertook a non-systematic, targeted review of multilateral programmes and initiatives launched since the Ebola outbreak.

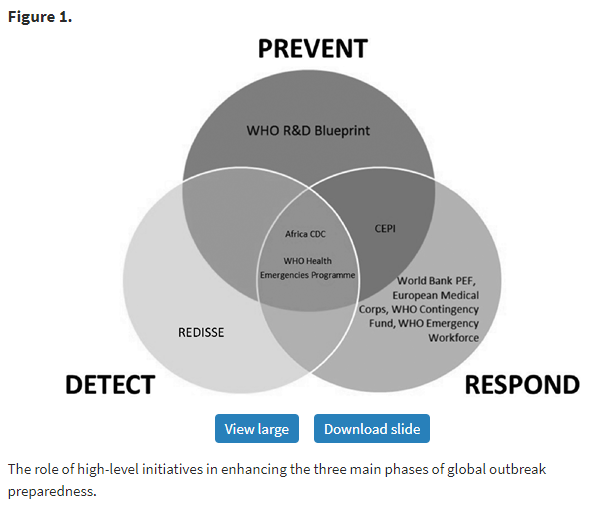

During our review, we found 8 multilateral programmes launched in response to the Ebola epidemic designed to shore up the system of outbreak prevention, detection, and response. We excluded sub-national programmes, bilateral initiatives, or programmes launched prior to the West Africa Ebola outbreak, such as the US-led Global Health Security Agenda.

Despite these promising new initiatives launched in the aftermath of the Ebola epidemic, progress remains uneven. Although these programmes have considerable potential to improve international outbreak preparedness and response capabilities, we found several weaknesses.

Funding

Perhaps the most obvious gap is that the majority of programmes we looked at failed to meet their funding targets. For example, at the time our research was conducted, the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness – a public-private-philanthropic partnership to accelerate vaccine development – reached 54% of its $1 billion funding goal. To be fair, the funding challenges presented here are emblematic of persistent underfunding in global health governance, as well as a lack of financial transparency in general.

A notable exception is the World Bank Pandemic Emergency Financing Facility – a $500 million insurance market – which was 100% backed by bonds and credit at the time of our research. This could reflect a growing appetite for innovative, market-based schemes for pandemic preparedness, as opposed to traditional donor capitalization.

Operations

Shifting from finances to operations, we found that the majority of new programmes are focused on the prevention and response phases of the outbreak. (We borrowed from the “Prevent-Detect-Respond” paradigm articulated by the Global Health Security Agenda). By contrast, far fewer programmes are working at the detection phase of pandemic preparedness.

This is problematic, since the literature reveals an urgent need to improve disease surveillance and detection, particularly at the human-animal interface, which gives rise to zoonotic disease spread. For example, failure to detect and diagnose Ebola in rural Guinea in the early days of the West Africa outbreak has been cited as a key driver of that epidemic.

The World Bank’s REDISSE project, which is designed to strengthen capacity for community-level disease surveillance in West Africa, is the only multilateral-led initiative we identified in the wake of the Ebola epidemic that responds directly to this need.

Ownership

We also found a significant disparity in the level of ownership of new programmes granted to high-income nations vs. low- and middle-income countries, which are most at risk of experiencing catastrophic epidemics. Most initiatives we found are sponsored by a small number of high-income and wealthy nations, such as Germany, Japan, and the UK, or philanthropic groups, such as the Gates Foundation and the Wellcome Trust. This calls into question the sustainability of those programmes, especially at a time when some Western countries appear to be turning away from multilateralism.

A key exception in this regard is the Africa Centers for Disease Control, which is financed and led predominantly by African Union member states. The Africa CDC provides a potential model for African ownership of pandemic preparedness on the continent.

The creation of mechanisms such as the European Medical Corps and the WHO Global Health Emergency Workforce provides evidence that the international community may be better prepared to put out fires from Brussels or Geneva than invest in national and local health service delivery systems, strengthen in-country capacities, or engage local communities affected by crises.

Conclusion

The findings from our investigation comprise an initial step in monitoring and evaluating the extent to which the measures enacted by the global community in the wake of the Ebola epidemic result in sustainable advances in public health preparedness. We hope future analyses will be conducted to complement this study and more thoroughly understand the impacts of these programmes on the global health security landscape.

Greater investments in regional or sub-regional arrangements that strengthen disease detection and surveillance at the community-level (i.e. the World Bank’s REDISSE project) would help to address current weaknesses in the global health security architecture. This would ensure a safer, more secure world for all involved, from Western nations to the global South.

Image credit: UNMEER