By Fiona Samuels (Overseas Development Institute), Ana B. Amaya (Pace University and UNU-CRIS) and Dina Balabanova (London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine

In this blog series we are giving a voice to practitioners, implementers and policy-makers involved in national COVID-19 responses in low- and middle-income countries. These posts seek to facilitate timely cross- learning by sharing opinions, insights and lessons on the challenges and actions taken by those on the COVID-19 front line.

As the COVID-19 pandemic unfolds, policy makers and different stakeholders seeking to identify effective responses have benefited from an unprecedented number of analyses and debates. Many of these are in public spaces—in open access academic journals and repositories as well as in the mainstream and social media. These provide compelling and thoughtful analyses on the wide-reaching effects of this pandemic ranging from the impact of the outbreak on healthcare workers, on the economy, on access to health services (e.g. family planning and mental health), on specific groups such as vulnerable populations including migrants, as well as the gendered dynamics of the pandemic.

This diverse and continual flood of information has, however, created a new set of challenges. In addition to the sheer volume of information, many of these contributions focus on specific questions such as how to better deliver services or ensure vital supplies, or propose policy responses and actions both within the health system and beyond, including, for instance, how to protect people’s livelihoods and the role of social protection. Policy makers are facing difficult decisions including how to ensure that adopting measures in some areas of the health system do not create unintended consequences in other areas (for instance, balancing the health impact of social distancing with the economic and social impacts). What seems to be missing is a way for policy makers to see the big picture and assess how different interventions fit together. Given the ever-changing situation, a rapid synthesis is difficult and can be still weighted towards particular interests led by well-known research and thought leaders.

We argue that one way to ‘quieten the noise’ and help policy makers who are hastily (re)formulating national plans is to step back and think at a more strategic or systemic level. Similarly, bringing together this sophisticated but somewhat disparate thinking and analysis into some form of coherent structure appears essential. While the role of strengthening health systems in responding to COVID-19 is beginning to be recognized, this is often high level and specific to particular settings. We suggest that a clear framework that can systematically incorporate various types of evidence and propose different kinds of action would not only facilitate current thinking around how to mitigate the effects of this pandemic, but also possible future pandemics and health emergencies.

Where do we start with strengthening health systems? A framework

Our first point is that strengthening the response to COVID-19 requires strengthening the health system. For this we return to our work under the Development Progress and Good Health at Low Cost projects which examined the paradox of how health systems in some low- and middle- income countries seem to perform better than what can be expected at their income level and often against the odds. As a way to think systematically about what these countries were doing right, we developed a framework which, we argued, helps to think about health systems strengthening systematically while at the same time providing practical advice for both policy makers and programme implementers on how to achieve better outcomes under significant constraints.

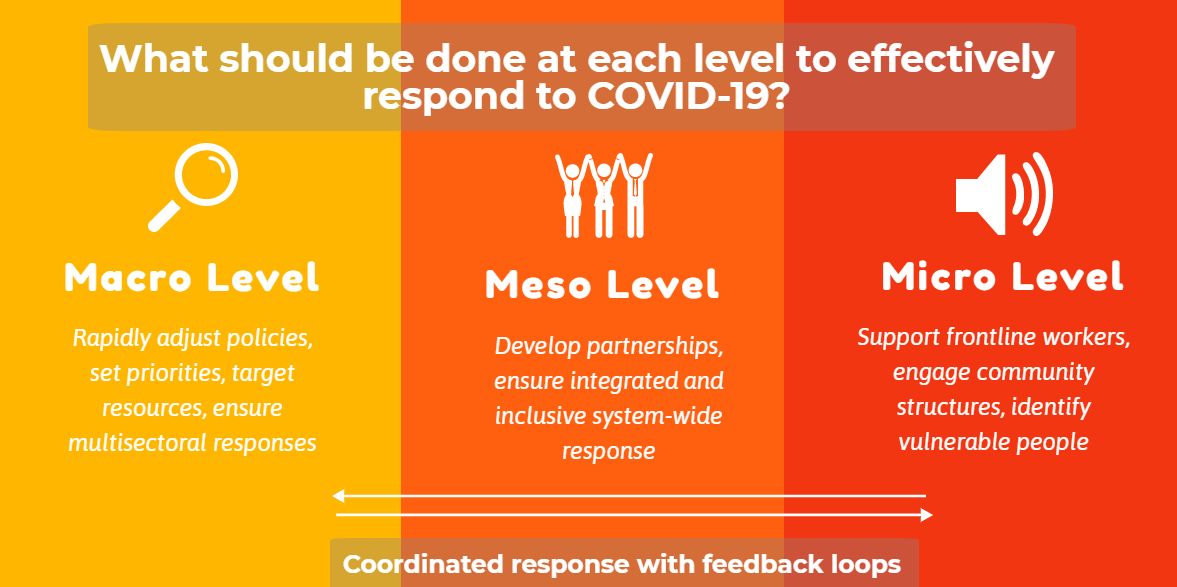

This framework was developed through combining a literature synthesis and case study findings from countries that had managed to reach relatively good health outcomes despite facing health system and political challenges. The Development Progress case studies explored maternal and child health (MCH) in Nepal, Mozambique and Rwanda and neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) in Cambodia and Sierra Leone. We identified three different levels within a health system that, we argued, were fundamental for achieving progress in health outcomes: the macro, meso and micro levels. Each level has its own roles and responsibilities, and actions at each level often interact with other levels, and this is also shaped by the global context.

What should be done at each level to effectively respond to COVID-19?

We argue that applying this multi-level framework can not only help decision makers think through what actions need to be taken at each level and by whom, but it can also help prioritise actions and their sequencing (or simultaneous actions). This can help avoid duplication and fragmentation and can also help to plan immediate, medium and longer-term strengthening of health systems. But what exactly needs to happen at each level?

Macro-level: Focus on specific health policies and target distribution of resources

At macro level, where policies are made and resources identified and prioritised, country governments need to be able to quickly adjust and/or develop new policies in keeping with rapidly changing contexts. This is relevant to both health but also other sector policies (e.g. the financial and social sectors). Hence, national-level policy makers need to define what economic stimulus packages are necessary to keep the economy afloat? How can the education sector adapt with the closure of schools? Could teachers be deployed elsewhere? Or which businesses should be deemed essential?

Regarding the health sector, existing health emergency plans should be reviewed and adapted for the pandemic. An appraisal of available health resources, including financing is necessary – both from government coffers and the donor community (if applicable) – and redirect resources if necessary. Assessing whether more health staff are needed and where (for example by recruiting retired workforce) and if an improved procurement system (primarily for medicines and equipment) is needed, is also essential. The macro level also needs to be able to marshal the private sector to, for instance, support in allocating its health human resources and infrastructure to the COVID-19 response, but also to, for instance, build ventilators and provide transport. Inter-sectoral collaboration should also be spearheaded at this level and could be fostered through setting up working groups and assigning a department or individual to lead / champion the response. Governments could also coordinate with the international community on best practices, leverage partnerships with countries for sharing resources (both in term of data but also supplies) and develop a regional response with neighbouring countries to stem transmission, when possible.

Meso level: Develop partnerships and coordination mechanisms between different stakeholders

At meso level, where policies are operationalised into programmes and interventions, coordination and development of partnerships with different organisations (government, NGO, faith based organisations, private sector) is critical to achieve a unified and effective response. Similar to the macro level, there is a need to identify a point person or ‘champion’ to spearhead the response at this level, also working closely with representatives from other sectors. Meso level authorities should ensure COVID-19 guidelines and resources (human, financial and infrastructural) from the national level are operationalised and allocated on a priority and needs basis and that the implementers of such plans are aware of latest initiatives and directives. These should draw on resources from the private and NGO sector while also making sure other urgent health needs are still being met. Effective communication is key between all levels, but it is especially crucial at this level which often serves as a go-between linking the other levels. Communication not only flows from the macro to the micro level but also vice-versa, for example, reporting on COVID-19 case burden or resource needs at micro level should then also inform directives developed at the macro level.

The meso level is also where integrated programming occurs. Thus, it would be critical to identify existing health programmes which also, for instance, include outreach activities where advice and care related to COVID-19 can easily be integrated. The meso level is also where a systematic approach to information provision would be important – information about COVID-19 should be made available in easily accessible formats, in local languages, in key locations, on radio and television.

Micro level: Mobilise local actors to raise awareness and generate support mechanisms

At micro level, raising awareness and support among those working on the frontline is crucial. Health workers at the community level (often volunteers) are a valuable but often underused resource in emergencies. Drawing them into the health system for the COVID-19 response by providing incentives would be important, especially in addressing needs in remote and hard to reach areas. Additionally, often community health workers are female and familiar with the population, as such they would have good access to girls and women, a group that may be particularly vulnerable due to often having less access to information but also, as carers, often being more vulnerable to contracting COVID-19 or experiencing mental distress or domestic violence due to isolation.

It would also be critical to engage communities in a response including working with community leaders, and building on existing local structures both governmental and non-governmental. Working with schools and teachers would also be fundamental to raise awareness and provide information about how to stay safe in a COVID-19 era; and, as has been shown elsewhere, educating school children can have a knock-on effect on families as children relay messages to household members. If schools are closed, existing structures and groups (e.g. parents and teachers associations) could still be mobilised to raise awareness, as could the skills of teachers as providers of information. Neighbourhood associations could also play a similar role.

Putting the jigsaw puzzle together to combat COVID-19

Many of these macro, meso and micro levels strategies are not new. They address ongoing challenges for health systems whether they are affected by COVID-19 or not, though arguably the current situation brings them even further to the fore. Indeed, many of these strategies have been considered or implemented during the current outbreak. However, we argue that these actions need to be considered as a package rather than designed and implemented in a reactive and piecemeal fashion. Some interventions that are not currently being prioritised may need to be enhanced to enable continued responses to COVID-19 (e.g. sustaining networks of volunteers and expanding their roles as intermediaries between the health system and the community, or creating capacity at municipal level to manage intersectoral responses). Many of these interventions are planned and financed in separate sectors, with little oversight of how they work together. While the nature of the pandemic and health systems are complex and responses will inevitably vary across settings, it is important to consider countries’ overarching principles and priority areas before deciding which actions to undertake. We argue that actions at all three levels need to be strengthened for an improved response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

In summary, applying this framework involves the following critical actions:

- Decision makers should take a holistic view of how to bring different elements of the response together and where to start in building a systemic response; this will involve prioritizing actions at each level, developing appropriate plans and identifying key actors that can execute them;

- Actions should be sequenced, considering also their longer-term consequences, this will also help policy makers develop strategic plans on where to start;

- Assess the capacity to carry out these actions, ensuring adequate funding for each level, but particularly the meso and micro level;

- Government, donors and the private sector need to come together at the different levels, but with strategic vision and oversight by the national/ macro level to ensure best use of resources, both financial and others;

- At each level, champions need to be identified and linked, coordination across health and other sectors needs to take place, and all involved in the response should be appropriately incentivized;

- Given the fast-changing nature of the epidemic, the results of interventions and lessons learnt at the meso and micro should be continuously fed back to the macro level for policy readjustment if necessary.

In conclusion, we argue that achieving coordinated oversight, across levels of the health system and across different sectors has a dual purpose – it may be key in building strong responses to COVID-19, while remaining essential for health system strengthening. The proposed framework is not a blueprint, characteristics of each level vary according to different contexts (political, administrative, geographical), and it is not static, changing over time. Ultimately, the aim should be to move from reactive responses to health emergencies to building effective systems that can rapidly mobilise and regroup to address ever-emerging threats in order to prevent a similar crisis in the future.

Associated Health Policy and Planning paper

Drivers of health system strengthening: learning from implementation of maternal and child health programmes in Mozambique, Nepal and Rwanda [Link]

Image credit: Global Financing Facility