By Mishal Khan (London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine)

This blog is extracted with kind permission and modifications from Singapore Sling.

The long flight back home from the Fourth Health Systems Research Symposium in Vancouver provided an opportunity to reflect on the plethora of thought-provoking discussions that took place in the waterfront venue. Reflecting my personal bias and interest of course, some of the most engaging sessions for me were related to the private sector in health, particularly informal providers and health markets driving excessive antibiotic use and, consequently, antimicrobial resistance.

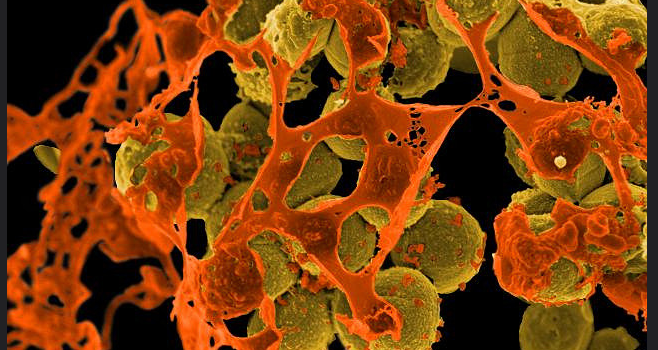

It was only in May last year that a global action plan to tackle antimicrobial resistance was endorsed at the World Health Assembly. Since then there has been a rapid mobilisation of funding and political support for action. In September 2016, antimicrobial resistance became the fourth health issue to ever have been discussed at the United Nations General Assembly, with all 193 member states agreeing to combat what the secretary general Ban Ki-moon referred to as a “fundamental threat” to global health.

One of the five strategic objectives of the global action plan on antimicrobial resistance is to improve awareness. Investments have been made towards a number of campaigns and infographics aiming to increase knowledge of prescribers or consumers. While attention to the issue of excess antibiotic use by private healthcare providers is urgently needed, Montagu and colleagues have highlighted that practice in private sector engagement is consistently moving in advance of evidence. To considerations about a strategy based largely on “knowledge improvement” among “prescribers” are that knowledge and training alone is not sufficient to change practice and that the stakeholders providing antibiotics around are probably more diverse than we imagine.

The homogenous group that we refer to as the private health sector, which is particularly active in Asian countries, comprises stakeholders far more varied than clinics and pharmacies. In fact, I prefer to refer to “dispensers” of antibiotics rather than “prescribers” to more accurately reflect the lack of regulation and understanding around antibiotic use. To illustrate what I mean, I share below some of the unexpected places selling antibiotics I have come across during my work on health systems strengthening and private sector engagement in low and middle income countries in Asia.

- Penicillin at the petrol stand

When driving from Phnom Penh, the capital city of Cambodia, to Kampot province in the south, I remember that the endless yellowy-green plains were peppered with roadside stalls set on wheels, selling coconuts and petrol stored in used water bottles. Since their business model is based on keeping an unconnected bunch of items popular with locals and travellers passing, these rickety stalls often also sell medicines, including antibiotic tablets. A study in Indonesia found that three quarters of stalls sold antibiotics. Needless to say, there is no temperature-controlled storage or limit on how much or how little is dispensed.

When driving from Phnom Penh, the capital city of Cambodia, to Kampot province in the south, I remember that the endless yellowy-green plains were peppered with roadside stalls set on wheels, selling coconuts and petrol stored in used water bottles. Since their business model is based on keeping an unconnected bunch of items popular with locals and travellers passing, these rickety stalls often also sell medicines, including antibiotic tablets. A study in Indonesia found that three quarters of stalls sold antibiotics. Needless to say, there is no temperature-controlled storage or limit on how much or how little is dispensed.

- Paan that makes your cough better

For those unfamiliar with it, paan is a popular concoction – consisting of a heart-shaped betel leaf wrapped around areca nut combined with tobacco or various other flavourings – chewed across South Asia, including Myanmar. I was most intrigued when I was told, on a visit to the Yangon, that for some paan is a go-to comfort food when they have a sore throat because it “seems to make it better”. On further probing local public health experts, I learnt that there may be a logical, if disconcerting, explanation for this. Some vendors are known to add crushed up antibiotics tablets to the paan, for clients complaining of throat ailments. The “sore-throat special”!

- Quacks outnumbering trained healthcare providers

It is perhaps not surprising that untrained or incompletely trained doctors, pharmacists and laboratory technicians (quacks) dispense antibiotics when they are not supposed to, or provide incorrect infectious disease test results. Colleagues and I have personally uncovered such malpractice in India and Pakistan. Of alarm, however, is how commonly such quacks are found. For example, regional surveys indicate that more than 70% of healthcare providers in rural India have no formal medical training.

It is perhaps not surprising that untrained or incompletely trained doctors, pharmacists and laboratory technicians (quacks) dispense antibiotics when they are not supposed to, or provide incorrect infectious disease test results. Colleagues and I have personally uncovered such malpractice in India and Pakistan. Of alarm, however, is how commonly such quacks are found. For example, regional surveys indicate that more than 70% of healthcare providers in rural India have no formal medical training.

The question of where antibiotics are available, particularly in the world’s most populous Asian countries, is an important one to consider when planning policy responses to encourage best practices in antibiotic use. Nothing can be assumed and local contextual knowledge is essential. It is not only the locations that antibiotics are available, but also the role of economic drivers of healthcare provider behaviour and links between for-profit providers and local policy actors that surprise many of us.

—

Image credits: Mishal Khan, NIAID, ilf_, travelwayoflife