By Alastair Ager, NIHR Global Health Research Unit on Health in Situations of Fragility, Queen Margaret University, Edinburgh.

There’s a growing interest in the concept of fragility. Initially just a new label given to ‘failed states’ to foster a more respectful form of engagement with countries marked by deep and persistent weakness of government, OECD interest has sparked a more nuanced approach. First there was the recognition that fragility is not just a condition that can affect a nation state but rather a broader range of ‘situations’. Then there was the insight that fragility is multi-dimensional. Conflict and insecurity is clearly a factor deepening fragility. But economic, environmental, political, and broader societal conditions are all now recognised as also contributing.

With colleagues at the NIHR Research Unit on Health in Fragility – based in Edinburgh, but with major partners in Lebanon and Sierra Leone – we have been exploring what a more nuanced understanding of fragility means for health systems and the communities there serve [see June 2019 WHO Bulletin editorial]. This includes a recent scoping review of over 377 papers that have used the term in the context of health provision.

Health systems and local communities

What’s emerging is the crucial importance in fragile situations of the interface between the health system and local communities. Obviously of relevance in all contexts, in situations of fragility this interface seems particularly vital for supporting access, quality and relevance of provision… and exceptionally vulnerable to fragmentation, distrust and exclusion.

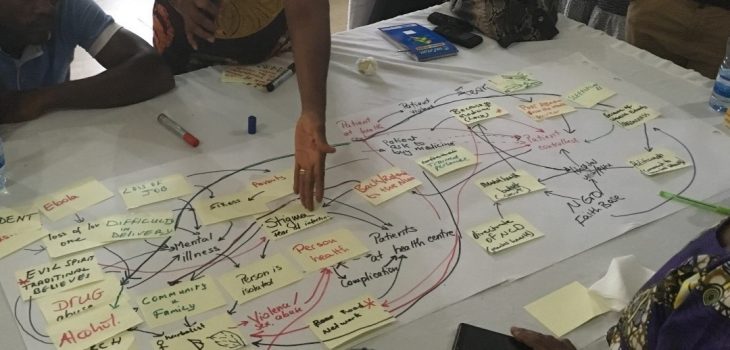

We’ve been developing methodologies to explore the dynamics of this interface across a range of fragile settings in the Middle East (including Syria, Lebanon and Jordan) and in West Africa (including Sierra Leone and the northern region of Ghana). Group model building – a participatory method based on system dynamics principles – has proved an especially powerful tool. This provides a way of working that is meaningful and accessible to both health providers and community members in eliciting their understandings of the barriers that need to be overcome in promoting health in situations of fragility. In so doing, it provides a mechanism that brings these groups together to consider appropriate systems interventions to address these challenges.

I have used a wide range of methodologies in my work in the field of global health over the last thirty years. But few have brought the vivid insights into the dynamics of health provision that group model building has provided, ranging from the reluctance of disclosing mental health needs beyond the household for fear of stigma and rejection, through the anguish of those with high blood pressure knowing that supply of their anti-hypertensive medication (or their income to purchase it) is unreliable, to the dawning realisation of health managers that it is the mechanics of health systems governance that drives staff non-compliance not their lack of care or competence. Trust is at the heart of each of these examples, and was a recurrent theme in our literature review across a very wide range of fragile situations (including those in high income and politically stable settings).

What’s the ‘big idea’?

So, in the context f health provision, what’s the ‘big idea’ in navigating fragility? It’s certainly important to be aware of the many different drivers of fragility, and that it has relevance as a concept beyond a listing of fragile-and-conflict-affected states. It’s likely useful to have that interface between health systems and communities (and the resources available through each) front-and-centre in our analyses of promoting health in contexts marked by fragility. It’s certainly worthwhile to consider the place of participatory research methods like group model building to explore that interface. But it’s probably trust – including the processes that have eroded it and the mechanisms to rebuild it – that is best seen as the core idea with which to navigate fragility. Indeed, measures to build trust within communities and between communities and state health providers are not only likely to support improved health provision. They are likely to redress some of the key drivers of fragility itself.

Image credit: Professor Alastair Ager

Professor Alastair Ager holds academic appointments as Director of the Institute for Global Health and Development at Queen Margaret University, Edinburgh (where he is Director of the NIHR Research Unit on Health in Situations of Fragility) and with the Department of Population and Family Health at Mailman school of Public Health, Columbia University. He has worked in the field of global health and development for over thirty years, after originally training in psychology at the universities of Keele, Wales and Birmingham in the UK. He has previously held academic positions with the University of Leicester and the University of Malawi. He has worked as a consultant across sub-Saharan Africa, south Asia, Europe and North America, with a broad range of agencies including UNICEF, UNHCR, WHO, Oxfam, Save the Children, World Vision, Lutheran World Federation and Islamic Relief Worldwide. He is active in several areas of research related to forced migration and humanitarian crisis including: the evaluation of humanitarian programming (particularly with regard to protection and psychosocial support of refugee children), processes of resilience in war-affected settings, and the engagement of local faith communities in supporting humanitarian response. He was appointed a Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh in March 2019. He currently holds the position of Deputy Chief Scientific Adviser to the UK Department for International Development.